Queer kids in rural America know what it's like to grow up scared.

Moises Serrano grew up in Yadkinville, North Carolina, population just under 3,000, about half an hour west of Winston-Salem. He wasn't just gay. His parents brought him across the border from Mexico when he was 18 months old. So: gay and undocumented.

As quickly becomes clear in Forbidden: Undocumented and Queer in Rural America, one of the movies in this year's Out Here Now — Kansas City LGBT Film Festival, the undocumented part of Serrano's identity is what brings much more pain and heartbreak.

That may be an eye-opener for white audiences. It was for the film's director, Tiffany Rhynard.

"I considered myself well-read and engaged in social issues," says Rhynard, who met Serrano when he gave a presentation on a college campus. "As I was listening to him talk the first time, I realized I hadn't really thought about this layer of privilege I had. I was a citizen of the country where I grew up. I had a legal driver's license, in-state tuition in the state where I grew up."

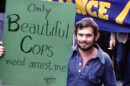

Much of Forbidden shows Serrano telling his story to anyone who'll listen — on college campuses like the one where Rhynard met him, at rallies, at meetings of the League of Women Voters and Rotary Club luncheons. Personable, attractive, articulate and calm, Serrano appears to be a natural leader.

And it's striking to realize that Serrano's bleak town — with its struggling main street, its knock-off chain stores and its trailer homes, it could be Anywhere, U.S.A. — is the land of opportunity for which his parents risked their lives.

"The person who hasn't come to the north doesn't know what it is to suffer," Serrano's mother says, fighting back tears as she remembers being separated from her children, spending five days without food and seeing cadavers along the trail into America. "We don't come to do wrong. We come to work, honorably. And just by not having papers, we are in the wrong everywhere."

Serrano's teachers and counselors tell him to dream big, so Serrano does. He graduates at the top of his class in 2007 and gets a small scholarship, which is when he realizes what "undocumented" means.

"All my dreams and aspirations shattered," he says. "I felt dirty to my core. I felt something was wrong with me, that I was the problem."

But Serrano finds a community of activist friends, and he falls in love, and begins speaking out.

His ascent into adulthood corresponds with increasing pressure on undocumented communities. The same year as he graduates, North Carolina passes its Real ID law — before then, anyone could get a driver's license with a tax ID number and a state ID; afterwards, people needed a Social Security card or other proof that they were in the country legally. Now Serrano's friends and family members are driving without licenses, fearing deportation just for going to work or to the grocery store.

The film shows the rise of the Tea Party, and Serrano knows of a girl who went out with a guy who thought it would be fun to take her to a KKK rally on a date. And the Obama administration deports more people than any other president.

At the same time, the Obama administration institutes Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), relieving pressure on Serrano and his friends who can now go to college, and the U.S. Supreme Court legalizes same-sex marriage, so it marks some progress.

Forbidden premiered at the Outfest LGBT film festival in Los Angeles last July, well before November's election, which has — and hasn't — changed things for Serrano.

"I've heard him say the undocumented community has been living with a certain amount of fear through the Obama administration," Rhynard says. "Certainly people are more afraid to come out of the shadows — the rhetoric surrounding the Trump administration heightened that. But in some ways it still feels the same."

Meanwhile, the film has screened at around 30 festivals and college events, many times with Rhynard and Serrano there for discussions afterwards. He is scheduled to appear via Skype after Saturday's screening in Kansas City.

"The response has been consistently positive. People are laughing at the right moments, crying at the right moments," Rhynard says. But also, "there’s information they didn’t know and are surprised to find out."

That's especially true for middle-class white audiences, Rhynard confirms.

"There has been the desire for more intersection in the LGBTQ movement, for it to be more inclusive of Black Lives Matter and the undocumented community, and we're starting to see that shift happen. This film being at festivals where the audience is predominately white has been really good," Rhynard says. "We're glad we’ve been included."

Inclusion is paramount at Saturday's screening of the film, which is co-presented by the Kansas/Missouri Dream Alliance.

“In a time full of hateful, divisive rhetoric aimed at both undocumented immigrants and the LGBTQ community," says festival organizer Jamie Rich, "this film shows how one dedicated person can make a positive impact for their community with compassion and earnest advocacy.”

As that one dedicated person, Moises Serrano will strike viewers as an extraordinarily poised and determined young man. Which gives the film an inescapable irony.

"There are millions of undocumented individuals, thousands of undocumented queer individuals," Serrano says at the end. "My story isn’t unique."

Forbidden: Undocumented & Queer in Rural America, followed by a Skype conversation with Moises Serrano 11 a.m. Saturday, June 24 at the Tivoli Cinemas, 4050 Pennsylvania Ave, Kansas City, Missouri, 64111, 816-561-5222. Out Here Now — Kansas City LGBT Film Festival continues through June 29.

C.J. Janovy is an arts reporter for KCUR 89.3. You can find her on Twitter, @cjjanovy.