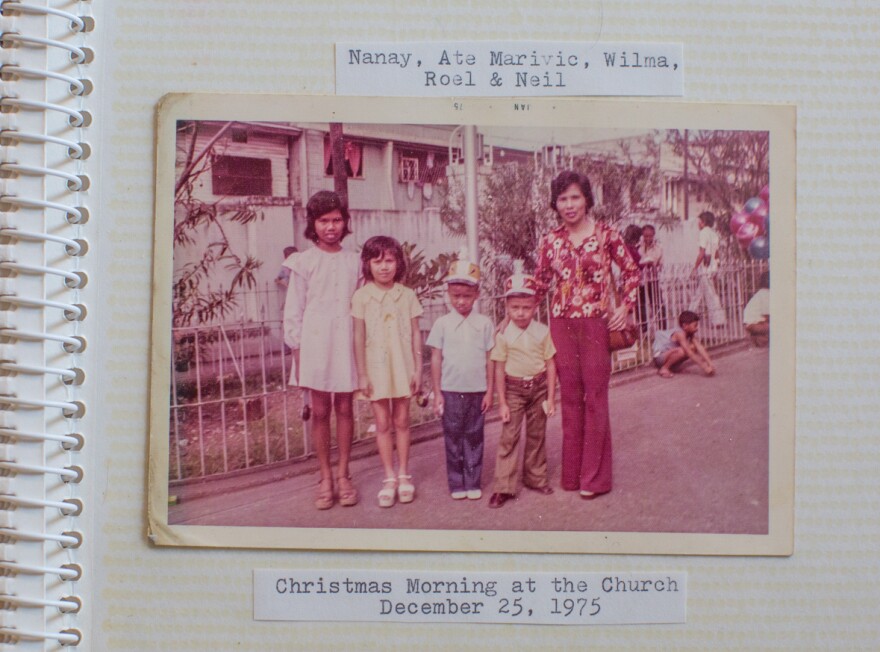

Cooking wasn't a matter of choice for Wilma Consul when she was growing up. Raised in the Philippines, she lost her father when she was 5 years old. A couple of years later, her mother, working long hours to provide for her four children, entrusted her second-born with the task of cooking for the family.

"My sister had to go to school full day," recalls Consul. She and her two younger brothers went to school in the afternoon. "I was left in the morning to do all the rice cooking, going to the market and basically cooking for the whole family."

Every morning, Consul went to the market to buy the ground meat, tomatoes and other ingredients for a dish called Ginisang Giniling (the Filipino name for picadillo, a Spanish dish that migrated to many former colonies).

.

It was a simple dish with sautéed meat that her mother had taught her to make. She'd cook it up for lunch for her brothers and herself, and there'd be leftovers for dinner.

The circumstances that led Consul to step into the kitchen as a little girl were unusual — her father's early death. But, she says, girls in the Philippines typically learn to cook early on. And Consul's chores weren't confined to the kitchen. She took on housework as well. Her sister would help — but not her younger brothers.

Her experience is pretty much the norm for girls globally. According to a 2016 UNICEF report, girls age five to 14 spend between four to nine hours a week helping their parents with housework — 40 percent more time than boys their age.

Cooking and cleaning the house seems to be the most common chore — two-thirds of girls do this. The next most common chores are shopping for the household, fetching water or firewood, washing clothes and caring for siblings.

"It's a universal reality," says Claudia Cappa, a senior statistics specialist with UNICEF and an author of the report. But "it is more prevalent in the developing world." This gender gap is especially stark in three African countries – Somalia, Ethiopia and Rwanda were cited as having the highest involvement of girls in household chores: more than half of girls age five to 14 spend at least two hours a day on household chores.

"We disproportionately burden girls," says Anita Raj, director of the Center on Gender Equity and Health at the University of California San Diego.

This largely stems from the fact that children's roles often mirror gender roles in their families, says Raj: "Girls go off with the mothers for what the mothers are doing. And boys go off with the father." In most countries, "women do greater loads of domestic labor." So their daughters follow suit.

This kind of early gender divide in the house has long term negative impacts on girls.

"This time [spent doing housework] is taking them away from schoolwork and socializing with other girls and thinking about their future," says Cappa.

Consul can relate to that. She is proud to have helped her mother — a single mother, struggling to provide for four children. But Consul resented it at the time. "I just wanted to play," she says.

Despite her daily burden of housework, Consul says she excelled at school. And her accomplishments made her mother proud. But many parents in developing countries don't care about their daughters' academic achievements. They just want them to marry and raise a family. Household chores prepare them for that, says Cappa. "Girls are pushed to think that this is the role they have in their family, this is what they are meant to do," she says.

That is why in many countries, girls drop out of school at the secondary level. "If families think that there is no value of girls attending school, they make decision to take girls out of school," says Cappa.

For Consul, that wasn't the case. In fact, she says her mother put a priority on education. Despite the family's financial hardships, she sent her daughters and sons to

private school to make sure they would all be able to find jobs and be independent. And they did, including Consul.

After the family moved to the United States, Consul earned a master's degree in journalism and later went to culinary school. Consul, now 52, splits her time between working as a journalist and a personal chef. When she cooks for herself, she often makes picadillo, the dish she cooked as a little girl. "It's kind of my go-to comfort food," she says. And with her mother now gone, too, the dish reminds her of home and of "taking care of her family," she says. "I love this dish a lot. It combines my childhood and my culinary vision of how to eat something healthy, without sacrificing the traditional taste."

Someday, she wants to teach her mother's picadillo recipe to her niece and two nephews, who are in their teens and early 20s and live in California. "It's something Filipino, it's easy [to cook]," she says. "And it will be something they have from their Lola, their grandmother."

Picadillo (Ginisang Giniling)

This recipe is courtesy of Wilma Consul. She calls it her "healthy twist" to picadillo, a hashed meat dish popular in Spain that made its way to former colonies like Cuba and the Philippines. (The Tagalog name "Ginisang Giniling" means "sauteed meat.")

Today, Consul cooks this comfort food with a few modifications — organic vegetables, turkey meat instead of pork or beef and edamame in place of peas. "I fuse our Filipino way of cooking with the French techniques I learned from [culinary] school," she says. "When cooked, the meat resembles that of American Sloppy Joe. But the taste is still truly Filipino."

1 tablespoon olive oil

2 cloves garlic, crushed and minced

1 medium yellow onion, diced

1 medium tomato, diced

4 tablespoons fish sauce

1 pound ground turkey (or chicken)

2 teaspoons Worcestershire sauce

1 cup water

Leaves from 3 to 4 stems of thyme

1 bay leaf, dried or fresh (or 2, depending on your taste)

3 parsley stems

1 celery stalk, cut in half

3 medium potatoes, Yukon or red, peeled and diced

4 small carrots, diced

1 medium red bell pepper, diced

1 15-ounce can tomato sauce

1 cup edamame

1 cup raisins, dark or golden (dried cranberries are also OK)

Heat olive oil in a large sauce pan or pot until oil starts to shimmer. Add minced garlic. Cook until it's about to turn brown.

Add onions, and saute until translucent.

Add tomato and 1/8th cup of the water. Cover and cook for 3 minutes. Uncover and crush tomatoes lightly with a wooden spoon.

When the water has almost evaporated, add the fish sauce and scrape up the dried bits. Enjoy the aroma.

Add the ground meat, breaking it apart with a spoon. Add Worcestershire sauce, then the rest of the cup of water. Add thyme, bay leaf, parsley and celery. Cover and bring to a boil.

Turn heat down to medium. Add the potatoes and carrots. Cover and simmer until tender.

Add bell pepper and cook for 2 minutes.

Add tomato sauce. Stir, cover and cook at medium heat for 2 to 3 minutes. Stir again, and turn heat to medium low.

Add raisins and edamame. Stir, cover and and cook for about 2 to 3 minutes until all vegetables are soft and the flavors have come together. Add the rest of fish sauce (2 tablespoons) and stir.

Turn heat to high, and bring to a boil (just a few seconds). Once it boils, turn the heat off and cover. Serve with brown or red rice.

Tips:

Share Your Hot Pot Story

Tell us a memory you have about a dish you love. Post a video or photo on Instagram or Twitter with the hashtag #NPRHotPot, and we'll gather some of our favorites and post them on NPR.org. Get the details here.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.