In about two weeks, Nebraskans will cast their ballots in the state’s primary election. That’s coming up on May 10th. That raises the question: how many votes does it take to win the governor’s seat?

To answer Nebraska Public Media News Morning Edition Host Jackie Ourada spoke to the Midwest Newsroom's data journalist Daniel Wheaton. This conversation has been lightly edited for clarity.

Jackie Ourada, Nebraska Public Media News Morning Edition Host: What are some key things we need to know about the primary election from a data perspective?

Daniel Wheaton, Midwest Newsroom Data Reporter: Thanks Jackie. I’ve been looking at previous primary election results in Nebraska, with an eye toward the governor’s race. In many ways the primary election is the most important election. Nebraska is a red state – there are 245,000 more Republicans than Democrats – so for a Democrat to win they’d have to get some 120,000 Republicans to vote for them in the general. Also, gubernatorial elections fall on presidential off-years too. Many voters don’t vote when we’re not deciding the presidency. So, those voting in this election tend to be the most politically involved.

Ourada: I see you pulled data from the Nebraska Secretary of State’s office. What are some of the top-level findings?

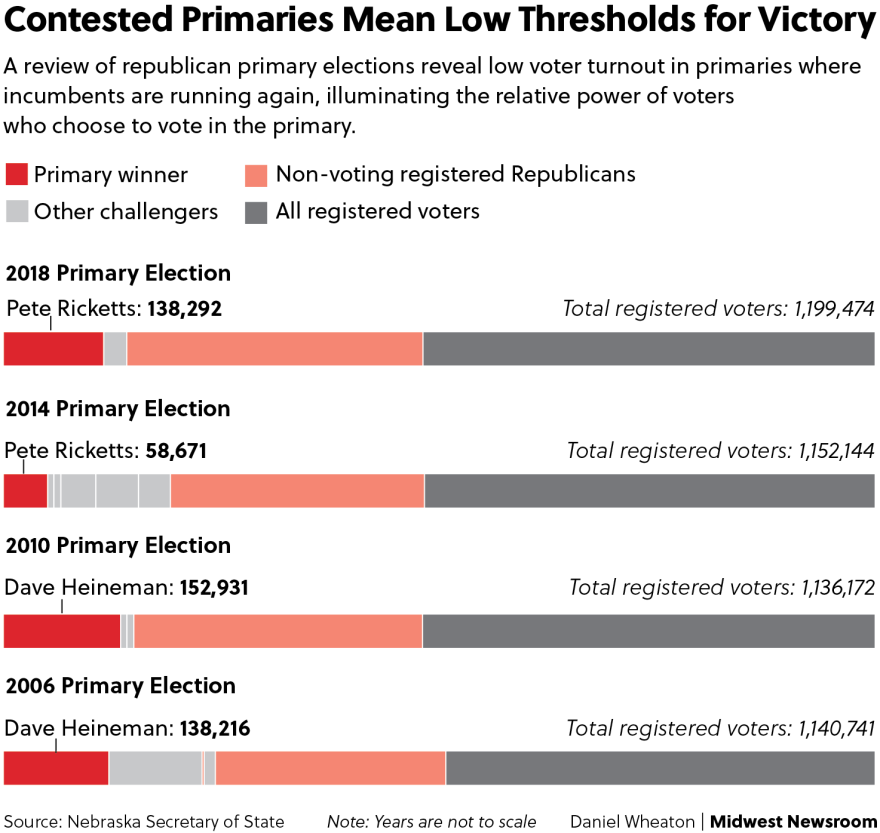

Wheaton: I was curious to find out what the actual voter turnout was. According to an analysis done by Pew Research, primary voter turnout tends to be low – below 25% nationally for both parties combined. As you may know, Nebraska’s Republican Party has a closed primary. That means that only registered Republicans can vote. In the past four gubernatorial primaries fewer than half of all republicans who could vote, chose to do so. In those elections we’ve seen turnout range from 29% to 47%. Comparing turnout in a closed primary to primary elections nationwide is apples-to-oranges, but it does suggest a heightened degree of interest for Nebraska Republicans.

Ourada: That 29%, what year was that?

Wheaton: That was in 2018, when current Governor Pete Ricketts ran for reelection. He had a challenger at the time, but overall, races with incumbents mean lower turnout. In 2018, Ricketts easily beat his challenger by winning about 138,000 votes – that’s a little bit less than half of the population of Lincoln to put that in perspective.

Ourada: This year Ricketts can’t run because he’s term limited. We now have a dozen candidates in the pool. What did the election results look like the last time the primary had a lot of candidates?

Wheaton: It certainly makes for a closer race. In 2014, there were six candidates on the ballot. Four of them were contenders and got more than 10% of votes. Obviously Ricketts came out on top with 27%. But, in a close second, was Jon Bruning with 25% of the vote. That’s a pretty tight margin, just 2,347 votes.

Ourada: That’s something to remember when someone says your vote doesn’t count! So, in the end, how many votes made Pete Ricketts win the 2014 primary?

Wheaton: 58,671. Much less than when he was just running to be re-elected. That number falls between the populations of Grand Island and Bellevue. It’s also just under 10% of all registered republicans in the state.

Ourada: With that in mind, what does this upcoming primary look like?

Wheaton: From what we know, it’s probably going to be a tight race. Three candidates: Charles Herbster, Jim Pillen and Brett Lindstrom all have a reasonable chance of winning the primary, according to several internal polls. It looks similar to how the 2014 race did. Still, A lot has changed in the past 8 years. Politics has become much more national – Donald Trump has campaigned for Herbster, and many attack ads are playing on national themes. Nebraska is a political outlier. We have the only Unicameral legislature. Only Nebraska and Maine split their electoral votes as well. It’s curious to see what national narratives play out here and which ones won’t.

Ourada: Looking forward, what questions do you hope to ask the data once the primary is over?

Wheaton: The biggest question I want to answer is if the Trump Effect still holds in Nebraska. Does having the former president campaign mean that more Republicans will turn out? It’s hard to say. I’m curious to know if turnout follows the pattern we discussed with non-incumbent elections, like when Governor Pete Ricketts ran for the first time.

The Midwest Newsroom is a partnership between Iowa Public Radio, KCUR 89.3, Nebraska Public Media News, STLPR and NPR to provide investigative journalism and in-depth reporting with a focus on Iowa, Kansas, Missouri and Nebraska.