When communities watch young people grow up, go off and never return, remaining residents and politicians often bemoan there’s been a “brain drain” — especially when such population loss means schools and businesses close.

But plenty of residents are full of love and pride for those communities, and some are working to identify their towns’ best attributes so they can attract new residents and achieve “brain gain.”

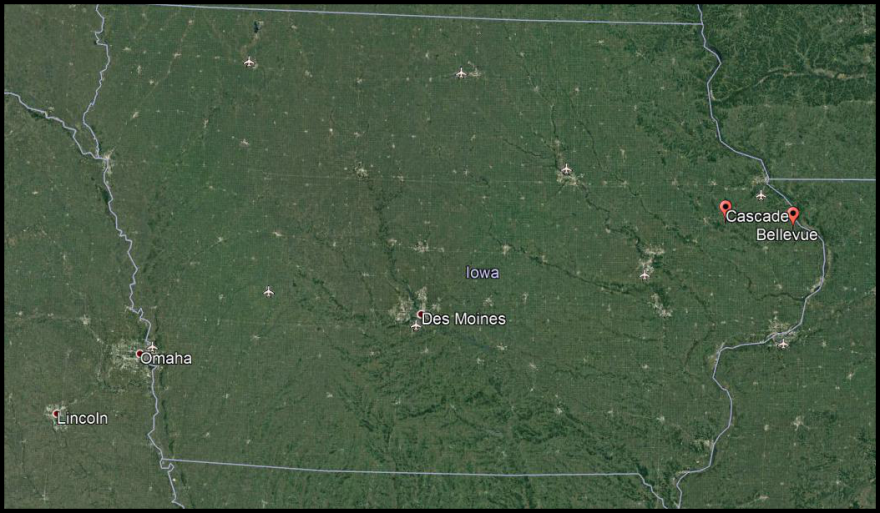

This effort is happening across New England and in the Mountain West, and is also evident in two Iowa towns.

Bellevue, Iowa

Ron Hansen and Julianne Couch wanted to move east from Wyoming, but weren’t sure where to go.

They found Bellevue’s scenic perch on the Mississippi River and friendliness of the local residents appealing and full of potential. The same went for the the two-story 1880s-era house that’d been carved into apartments for 40 years, which the couple restored.

“Half the people in Bellevue have lived here at one time or another, or know somebody who did,” Couch said of the home, “or have been to a party here or something.”

The town of about 2,200 people had everything Couch needed, she said, like a hardware store, a vet clinic for their dog, Archie, and one grocery store — not 20. But there was one other thing that made the move possible: town-wide fiber optic. Couch teaches online courses and requires fast internet.

It’s the sort of forward-thinking innovation that can help a town thrive rather than struggle. Even so, Bellevue has lost about 5 percent of its population since 2005.

Couch participated in a planning process, called Community Heart and Soul, that’s also been used in rural areas in Illinois, Colorado and many other states, to help improve her new hometown. It aims to survey as many residents as possible so a town’s core values can be clearly stated and resonate with everyone. Naming those priorities — Bellevue’s included safety and natural beauty — helps communities attract more people and businesses.

Downtown improvements also made the list, and Bellevue Area Chamber of Commerce director Carrie Weaver said she thinks that’s coming.

“There's a building that's on the corner and it's empty and I think if that building can get something cute in it, I think that will get the ball rolling,” she said. “I think it’s going to take that one building because it’s right in the middle of downtown.”

She said when she worked in Strawberry Point, Iowa, she saw the downtown transform after one pivotal renovation; five years later, there isn’t an empty storefront to be seen. She said she thinks that could be Bellevue’s future.

Cascade, Iowa

About 45 minutes west of Bellevue, the Cascade High School Cougars baseball team plays summer home games in front of lots of local fans, not all of whom have a player on the team. This community rallies around its student-athletes; the boys and girls high school basketball teams were state champs this year.

Kathy Weber married a man who grew up in Cascade, but the two initially lived in Dubuque, about half an hour away. A dozen years ago, they settled here.

“We moved here after we had our son,” said Weber, who was selling tickets to the ballgame, “because we wanted to raise him here. We wanted to live in a small town.” Weber still commutes to Dubuque for work at a local college.

Getting natives to come back, potentially with a spouse, is a great way for a town to grow, but it has to offer reasons to return.

Most of the storefronts in Cascade’s downtown are empty, and that doesn’t reflect the dynamic, caring community that Molly Knuth loves. She returned to her hometown after college.

“The thing that I mostly remember from growing up is that it was a little more … vibrant, if you will,” Knuth said.

As a parent, she appreciates that all of the schools, public and parochial, were recently renovated and she points proudly to the $1 million day care center built mostly from community donations.

The population in Cascade is up nearly 12 percent since 2005, but attracting brand-new residents who don’t have a family connection is a tall order.

Iowa State University community planning professor Sara Hamideh said newcomers go where they see quality of life improving. Those towns have people who volunteer, donate money for local projects and generally support each other. Plus, residents have to be open to new ideas. And then, Hamideh said, places need to market themselves.

Bellevue has an annual Fish-tival and Cascade celebrates HomeTown Days. Those things can put a town on the map of prospective visitors.

“Web presence is a big part,” Hamideh said, “but also having something going on, no matter how small you are, that keeps you on that map, is also key.”

Cascade, like Bellevue, is also undertaking a Community Heart and Soul project. Knuth is on the organizing committee along with Linda Hoffman, whose family has run a gas station and convenience store on the edge of downtown since 1961.

In 2002, a state highway bypass opened, pushing cars away from Cascade.

“Traffic’s a lot less,” Hoffman said, “but I’ve notice more out-of-towners have moved to town and I think that part of the deal is they like the small town.”

And it’s important to keep the people who already live in town, which requires jobs. Cascade’s working on that, too.

Halter, a Dutch manufacturing company, opened its North American headquarters here a couple years ago. Daren Manternach came on as a sales rep after years of running a bar downtown. He said he knew of another man who was looking for a career change, even considering leaving the state.

“And he was very intrigued when he saw that Halter, a robotics company, was in Cascade, Iowa,” Manternach said.

That man now works at Halter, putting a twist on a common Iowa adage: If you invite people to help build it, they will come.

Amy Mayer is a Harvest Public Media reporter based in Ames, Iowa. Follow her on Twitter: @AgAmyinAmes