The first time Rich Acciavatti saw “Carnival of Souls,” he was stuck in bed with the chicken pox. He couldn’t have been more than 8 years old the afternoon it came on TV in the early 1960s. He says he couldn’t sleep for a week.

“I was always talking about ‘Carnival of Souls,’ like through school, through high school, grammar school,” says Acciavatti, a New York-based musician who runs the film’s fan page on Facebook.

“I said, 'This is the scariest movie ever. I hope it comes back one of these days.’”

Filmed mostly in Lawrence, Kansas, “Carnival of Souls” did come back, but not for almost three decades. In the years following its 1962 premiere, it became known as “the movie that wouldn’t die” and developed a cult following thanks to late-night television and screenings in arthouse cinemas and on college campuses. Today, it is one of the most beloved films to come out of the state of Kansas.

But for a time, it seemed “Carnival of Souls” was dead in the water.

In the nightmarish, atmospheric story of a woman who cheats death but doesn’t get away with it for long, church organist Mary Henry (played by Candace Hilligoss) survives a car accident that kills two of her friends. She flees her home of Lawrence, Kansas, for Salt Lake City. There, her past begins to catch up with her. She is dogged by glimpses of a ghostly figure, known only as “The Man,” who eventually lures her to an abandoned carnival pavillion to meet her fate.

Director Herk Harvey and screenwriter John Clifford both worked in Lawrence at an industrial film production company called the Centron Corporation. They made “Carnival of Souls” for a mere $30,000 (about $250,000 today) shooting in Lawrence except for some key scenes filmed in Salt Lake City.

It quietly premiered in 1962 and had a modest run at drive-in theaters before largely disappearing. Harvey sold the distribution rights to a company called Herts-Lion. Herts-Lion went belly-up within the year, and Harvey never saw a dime.

But horror fans continued to whisper about the film. WOR-TV in New York City gave it a late-night timeslot for a while in the 1960s, where it was seen by Acciavatti and other present-day devotees. More television stations picked it up as the years went by. There were bootleg tapes in basements and mentions in film magazines. The buzz around “Carnival of Souls” slowly got louder until its fans brought about a renaissance. Audiences couldn’t resist it.

“When this hit the film screenings on college campuses, I mean, there was an explosion of people like getting interested in this and seeing it for the first time, and just being totally astounded by its ambience,” Acciavatti says.

“‘Carnival of Souls’ begs the great question like, 'How did this happen?'” says Kansas City filmmaker Tim De Paepe, a student and friend of Harvey’s when the director taught in the film department at the University of Kansas. “You can't necessarily predict or drive the destination of a film. I mean, it's just certain films — just for whatever they are — sort of find their way to connect with the pulse of an audience under extraordinary, extraordinary obstacles that are placed in its way.”

In November 1989, 27 years after the film premiered, Harvey, Clifford, Hilligoss and other members of the film’s cast and crew gathered at Liberty Hall in Lawrence for a special screening of the film in its original 35 millimeter format.

The event came ahead of a limited theatrical release at arthouse cinemas and film festivals around the country. Earlier that day, the crew appeared across the street at the Eldridge Hotel for a press conference. Harvey painted his face white for the occasion, donning the spooky, silent film-star look of The Man, whom Harvey also played in the movie. (Footage of the conference is available online and in the special features of the “Carnival of Souls” 2016 Criterion Collection release.)

“Lawrence has been wonderful to John (Clifford), to me,” Harvey says at the conference. “It’s been a great place to make films, and this film — I don’t know how it’s happened, quite frankly. I don’t know how it’s getting this revival, but it’s happening, and it’s beyond our control.”

De Paepe says Harvey appreciated the newfound love for his movie. It was his first and only feature film, and he was proud of it.

“He loved it. He loved it. Finally,” De Paepe says. “I think that's what really sort of pushed Herk to (say), 'Yeah, I can reclaim this.'”

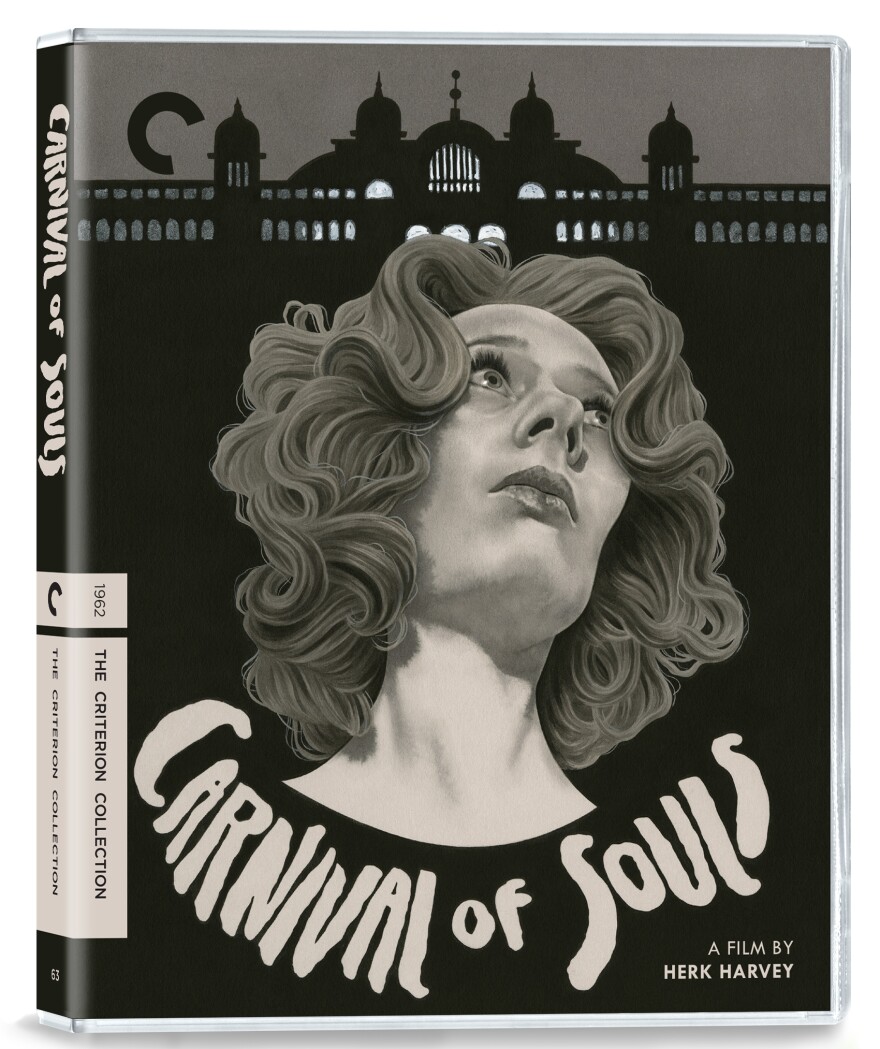

It’s not hard to find “Carnival of Souls” today. It’s available on most major streaming platforms, and you can rent it on Prime Video and buy it on iTunes. Its general availability is due in part to the Criterion Collection, a home video distribution company that licenses artistically significant films from around the world. Criterion released “Carnival” on DVD in 2000 and on Blu-ray in 2016.

Susan Arosteguy produced the film’s 2016 Criterion release, overseeing the transfer from film to digital and the inclusion of supplementary material. Arosteguy first saw “Carnival of Souls” working part-time at a video store while a student at the University of Colorado Boulder.

“It was just one of those B-movies that was sort of infamous,” Arosteguy says. “I just thought it was just a really sort of amazing example of a B-movie that's still very artful and affecting. I just loved it, always.”

As part of the Criterion Collection, “Carnival of Souls” is shelved alongside the likes of Akira Kurosawa’s “Seven Samurai” and Federico Fellini’s “8½.” Arosteguy says it’s right at home. Harvey, a technically accomplished filmmaker due to his years at Centron, was also a cinephile. He credited French director Jean Cocteau as one of the greatest influences behind “Carnival of Souls,” particularly the films “Beauty and the Beast” and “Blood of a Poet.” He said he wanted to achieve the “look of a Bergman and the feel of a Cocteau.”

“He always loved all those sort of foreign art films,” Arosteguy says. “He kind of nailed it actually in how the movie looks and the whole feeling of it.”

Harvey died in 1996 and Clifford in 2010. Most of the cast and crew are gone — except for lead actress Candace Hilligoss, who still makes occasional public appearances related to the film.

But traces of “Carnival of Souls” can still be seen in Lawrence and beyond. Liberty Hall displays the panels of Mary Henry’s organ in its video store. Oldfather Studios, the former home of the Centron Corporation and, later, the KU Department of Film & Media Studies, dedicated its sound stage to Harvey shortly before his death. Filmmaker George Romero credited “Carnival of Souls” with inspiring the makeup in his seminal work “Night of the Living Dead.”

Ultimately, “Carnival of Souls” is a Midwestern, cinematic Cinderella story: A tiny film produced on a shoestring budget and a prayer became a cult classic.

“I think the story of ‘Carnival of Souls’ is still one of those that for me resonates as the ultimate independent film success or what an independent film should be,” De Paepe says. “That's a wonderful, wonderful little mystery right there.”

Follow KCUR contributor Courtney Bierman on Twitter @courtbierman.