Missouri was beautiful.

“Many parts of these prairies of the Missouri are extremely beautiful, resembling cultivated countries, rather than the savage rudeness of the wilderness,” author Washington Irving wrote after an 1832 deer hunt near Independence.

Missouri was a slave state.

Joel Palmer, an Indiana farmer who traveled through Jackson County in 1845, wrote that the crops he noticed near Independence, “cultivated generally by negroes, consisted of hemp, corn, oats and a little wheat and tobacco.”

On Tuesday, Missouri residents observed the 200th anniversary of the state’s 1821 entry into the Union.

The challenge for state officials and historians, as well as more casual observers, has been how to mark the moment and note the bicentennial in ways that address the state’s rich history, which includes struggle, complex collisions of culture, triumphs over adversity – and slavery.

At the Missouri Bicentennial Commission website, residents can access a long list of community photo exhibits and ice cream socials, as well as details regarding the Missouri state bicentennial quilt.

Also available online is information regarding “Struggle for Statehood,” a traveling exhibit scheduled to be installed in Lee’s Summit in September. The display examines the indigenous peoples who once occupied the region.

It also addresses Missouri’s slavery legacy, and how the state’s admission to the Union contributed to the rise of anti-slavery dialogue in what came to be called “The North” and also how the sentiments articulated before, during and after statehood contributed to the bitter debate that led to the Civil War.

“Missouri was born in the midst of controversy about slavery and its extension into the West,” said Diane Mutti Burke, a professor of history at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, who served as a consultant on the exhibit.

The display will be installed from Sept. 21 through Oct. 26 at the Summit Center, at the University of Central Missouri-Missouri Innovation Campus, in Lee’s Summit.

“I felt it was important for the exhibit to showcase the sometimes challenging history of Missouri,” added Jon Taylor, a University of Central Missouri history professor who is serving as host coordinator.

“It’s a very complicated story.”

Quilts and marionettes

And then there’s the Harry S. Truman marionette.

Across the Kansas City area, historical societies, nonprofit groups and civic organizations – while acknowledging the historical anniversary – also have been making the moment their own.

That’s what organizers had hoped would happen.

The bicentennial observance is accordingly large, with participation by 114 state counties. The challenge faced by planners has been how to make such a large event local.

“As a matter of philosophy, we knew we wanted to do something that was truly statewide,” Michael Sweeney, bicentennial coordinator with the State Historical Society of Missouri, said recently.

“But how do you do that in a state that is, for lack of a better phrase, fairly fragmented? There is the urban-rural divide. But, even beyond that, my friends down in the Missouri Bootheel often identify far more with Tennessee and Arkansas.”

Part of the challenge facing organizers has been to gently remind Missouri residents that they share a common legacy. That can be delicate, given that anything that smacks of an official directive from Jefferson City can play poorly among some residents, Sweeney said.

That became clear during focus group discussions.

“There was the sentiment that ‘I don’t need the state to come down here and tell me how to do the bicentennial,’ ” Sweeney said.

One answer was to ask communities to come up with their own proposals that could showcase specific regions but also reference a shared Missouri heritage.

“We wanted to see some level of local control, but how is that done without being parochial?” Sweeney said. “If you emphasize the local too much, you end up with 100 different things with no unifying theme.”

In response, Sweeney and colleagues came up with community engagement projects.

One example was the Missouri quilt initiative.

The State Historical Society of Missouri worked with area quilting organizations to talk up a bicentennial quilt, asking that quilters submit proposed blocks – small squares of fabric – that conveyed some sense of their home county’s history or culture.

Submissions arrived from across the state and since the quilt’s completion, Sweeney has helped drive it across Missouri.

He recently brought the quilt to the Courtyard Community Center in Plattsburg, in Clinton County, north of Kansas City.

There Sweeney watched as local quilters first examined the block representing Clinton County – and then stepped back to take in the entire quilt, and consider their own county’s block in context of all the others.

“So, that kind of moment happened,” Sweeney said.

Another initiative was the bicentennial “Community Legacies” program, which seeks to showcase Missouri traditions, places and organizations.

Examples, found at the bicentennial website, are reports detailing the Ozarks Genealogical Society of Springfield; the Madonna of the Trail sculpture, a monument to women of the westward migration unveiled in Lexington in 1928; and the “Big Tree” of McBaine, Missouri, near Columbia, considered to be the state’s largest bur oak.

Sweeney, meanwhile, prepared a report about Kansas City’s annual Juneteenth celebration, which commemorates the end of slavery in the United States.

For that, he went to the Kansas City observance’s origins, interviewing Makeda Peterson, whose late father, Horace Peterson III, founder of the Black Archives of Mid-America, organized Kansas City’s initial Juneteenth celebration in 1980.

“The report included how the organizers wanted to see the celebration in five years,” Sweeney said.

This past June, well after Sweeney completed his report, Juneteenth became a federal holiday.

Also listed on the Missouri bicentennial website are the shows scheduled to be performed by the Puppetry Arts Institute of Independence at the National Frontier Trails Museum, 318 W. Pacific Ave., in Independence, on Aug. 13 and 14.

A Harry S. Truman marionette will serve as master of ceremonies for a family friendly program incorporating several state cultural symbols, among them the Missouri mule.

Kraig Kensinger, institute artistic director, believes the lighthearted presentation sits nicely alongside more weighty bicentennial lectures or symposia detailing Missouri’s backstory. He considers the support the institute has received from a variety of funding sources, among them the Missouri Humanities Council and the National Endowment for the Humanities, as evidence of that.

“I personally think we are one of the most unique bicentennial programs,” Kensinger said.

“A lot of the bicentennial observance is made up of lectures and slideshows. But we are one of the few groups presenting a program that people of all ages could enjoy.”

“Just and fair”

Slavery in Missouri was visible early, and one reason why was its garden-like appearance and rich unspoiled soils, as described both by prominent visitors as well as new residents.

Washington Irving, author of “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” noted that during his 1832 visit to Independence he had witnessed “scenery that only wanted a castle, or a gentleman’s seat here and there interspersed, to have equaled some of the most celebrated park scenery of England.”

He also insisted that the “soil is like that of a garden, and the luxuriance and beauty of the forests exceed any I have ever seen.”

The land’s apparent natural abundance helped draw many to the new state.

While researching her 2010 book, “On Slavery’s Border: Missouri’s Small-Slaveholding Households, 1815-1865,” Diane Mutti Burke found evidence regarding Missouri’s early appeal in the 19th century letters written by those who already had arrived there.

”White settlers often wrote back to their family members, giving unrealistic, almost over-the-top descriptions of how wonderful Missouri was,” said Mutti Burke, adding that the correspondents tended to exaggerate potential crop yields and profits.

“They often were trying to convince their loved ones to move westward with them – almost trying to reconstitute the communities they had left.”

Some who received those letters, perhaps facing their own farms depleted from years of tobacco cultivation, went west, sometimes taking their own enslaved persons with them.

Subsequently, slavery in Missouri often operated on a much smaller scale than it did in the “plantation” South.

That, however, brought its own complications.

Missouri slavery, according to Mutti Burke, operated with an almost “intimate” quality, in that owners often lived in close proximity with their enslaved persons, sometimes in the same buildings. Sometimes owners worked alongside their enslaved persons in the farm fields and homes.

But those kinds of work relationships, she added, “could explode at various times, when misunderstandings occurred or when expectations were not met.”

For motivated researchers, direct evidence of Missouri’s slavery legacy can still be retrieved.

Documents archived today by the Clay County Archives & Historical Library in Liberty detail the complex litigations Missouri slavery could generate before the Civil War.

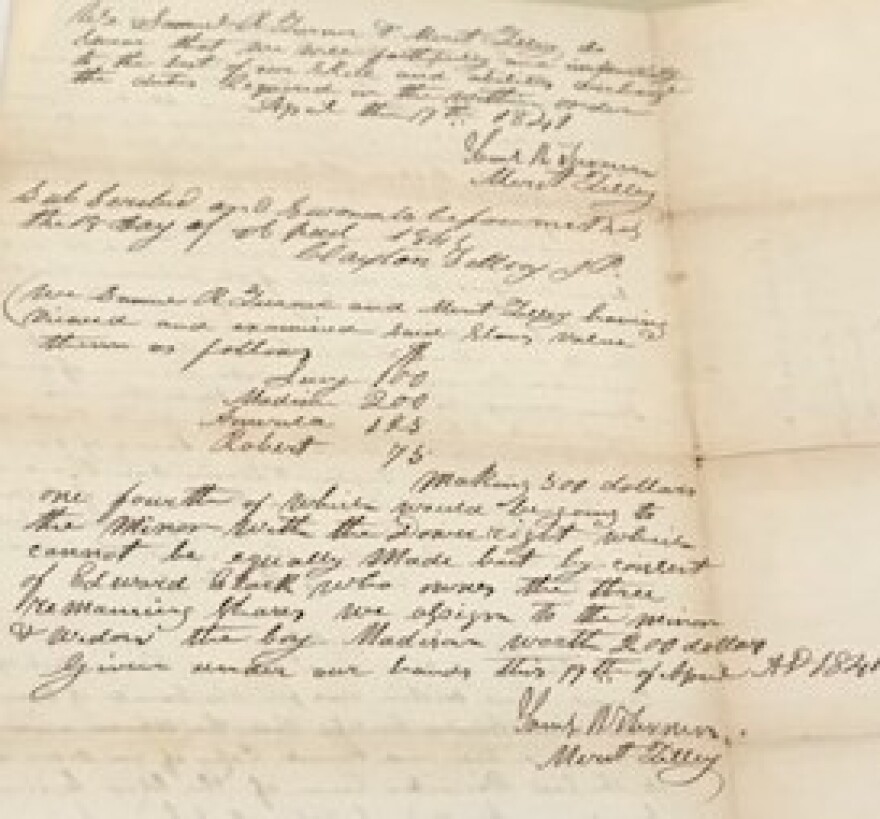

One circuit court file dates to 1840, when resident Edward Clark and three others – one of them an infant – petitioned for the formal partition of four enslaved persons among them.

The proceeding included the naming of three commissioners who placed dollar values on a woman named Lucy, two boys named Robert and Madison, and a girl named America.

According to the now-yellowed documents, the commissioners valued Lucy at $100, Madison at $200, America at $125 and Robert at $75.

Commissioners assigned one-fourth of the $500 total value to the infant.

In handsome penmanship, a court clerk recorded the matter’s final disposition in a large ledger book, noting the division had been found to be “just and fair,” and that the petitioners had agreed to pay court costs “in proportion to their respective rights in said property.”

Austin King, a state circuit court judge who also served as Missouri governor before the Civil War and a member of Congress during it, signed the ledger book on April 20, 1841, noting the proceeding’s conclusion.

“We don’t take it mildly that we are entrusted with these documents,” Tony Meyers, archives president, said recently.

“I am proud that we have been able to partner with the Clay County Circuit Court to make these records available to anyone who wants to examine them.”

Some visitors to the Liberty archives, meanwhile, have been researching how to properly honor those Black residents of Clay County who are buried in unmarked graves.

Organizers of the Liberty African American Legacy Memorial seek to engrave into granite the names of the more than 700 Black area residents who, according to organizers, are buried mostly in unmarked graves across an approximately six-acre spot at what is now the city’s Fairview & New Hope Cemetery.

“We are rewriting the history books with this memorial that will help bring about reconciliation among our residents,” said Cecelia Robinson, a retired William Jewell College English professor who is also a member of Clay County African American Legacy, Inc., which is coordinating the effort as its bicentennial project.

“Missouri was a slave state, and African Americans have been here since the beginning,’ Robinson said. “With this project we want to honor the African Americans who helped build this community.”

A 9:30 a.m. groundbreaking is scheduled for Saturday, Aug. 21, at the cemetery at 101 E. Kansas St.

Recalling cultures

Today evidence of Missouri’s slavery legacy exists across the Kansas City area, and not only in archives or libraries.

At the 3-Trails Transit Center at 9449 Blue Ridge Blvd., commuters riding Kansas City Area Transportation Authority buses can learn of travelers who themselves were in transit close to 200 years ago.

Dedicated in 2018, the enhanced bus stop marks the path through south Kansas City where the Santa Fe, Oregon and California trails shared the same corridor, and also documents some of those who traveled along the overland routes.

They included three Black women, all of whom had been enslaved during their lives.

Meanwhile, more infrastructure-embedded evidence of slavery’s ramifications can be found in Independence.

There, small plaques placed in Independence Square sidewalks mark the spots where two followers of Mormon prophet Joseph Smith, Jr. were tarred and feathered in 1833 and also where, on the same day, a Mormon printing shop was demolished.

Both plaques are part of the Missouri Mormon Walking Tour, installed in 2000 by the nonsectarian and nonprofit Missouri Mormon Frontier Foundation.

Smith’s followers began coming to Jackson County after he, in 1831, had declared Independence the church gathering place.

Settlers already living in Jackson County were suspicious of the Mormons for their anti-slavery sentiments, as well as their swelling numbers, which they took as a possible political threat.

Accounts of the unpleasantness that followed can be found not far away at the Independence Visitors Center, operated at 937 W. Walnut St. by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

There, hosts can guide visitors to a replica of the demolished print shop and also show a short film that briefly depicts the violence that ultimately drove the Mormons out of Jackson County, north across the Missouri River, and into Clay County.

There, at the Historic Liberty Jail, now operated by the LDS church at 216 N. Main St. in Liberty, guests can learn the rest of the story, which included the incarceration of Smith and several of his followers for about four months.

Hosts will lead visitors to a reconstruction of the jail, detailing the deprivations endured there and also explaining the revelations church members believe Smith received there.

Smith and his followers eventually escaped custody in 1839.

“There was obviously conflict between the two communities and there are two sides to every story,” said D. Glen Esplin, director of LDS historic sites in Missouri. “The full story needs to be told and that is what we are trying to do.”

Another key local culture is recalled in the “Struggle for Statehood” digital exhibit, jointly created by the Kinder Institute on Constitutional Democracy at the University of Missouri and the Missouri Humanities Council.

A virtual keynote address to accompany the exhibit’s installation in Lee’s Summit will be delivered by Tai Edwards, a Johnson County Community College associate professor and scholar on the Osage Indian nation.

“The history of the Osage is a powerful one,” said Taylor of UCM. ”While there were other Indian nations present in what is now Missouri, the Osage dominated.”

At one point the Osage population in Missouri stood at perhaps 10,000, Taylor said.

“In the colonial period, typically, the French and Spanish would dominate,” he said. “That’s not what happened in Missouri. Neither the French nor the Spanish had the numbers the Osage did.”

And yet, for a variety of reasons, the Osage nation largely had vanished from Missouri by the mid-1820s, Taylor said.

A detailed explanation of the Osage Nation’s time in Missouri can be found at the Fort Osage National Historic Landmark, near Sibley in northeast Jackson County.

Dioramas and displays explain Osage culture and how the nation’s members interacted with the military personnel and agents who operated the trading post and garrison which, when built in 1808, represented the westernmost United States military outpost.Altered landscapes

Less retrievable, however, is the sight of the Missouri River as experienced by explorer William Clark, who noted the unique location during his 1804 expedition with colleague Meriwether Lewis and whose memories of it contributed to the fort’s construction.

“The years of channel projects by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers have changed the river,” said Fred Goss, site administrator for Jackson County Parks and Recreation, which operates the reconstructed fort.

But it’s not impossible to experience something close to what visitors like Clark and Washington Irving described.

The Missouri River bottoms once featured many wetlands, sloughs and oxbow lakes in addition to the original meandering river, said Bill Graham, Kansas City area media specialist with the Missouri Department of Conservation.

A reasonable facsimile of those sights, he said, can be found at the Little Bean Marsh Conservation Area in northwest Platte County. There, a road leads to a parking lot with a trailhead, and the trail leads back into the marsh area and eventually to a platform overlooking it.

“How it looks depends on the season and the weather conditions,” Graham said. “But visitors will see a sight Lewis and Clark saw.”

The explorers camped in the area in early July during their 1804 expedition, and noted the area in their journals.

“It’s a fine example of a Missouri River wetland, and the trees in the low-lying areas surrounding it are likely typical, too,” Graham said.

Closer to downtown, Hidden Valley Park – maintained by Kansas City Parks and Recreation – in southern Clay County offers trails leading southward towards the Missouri River that lead into deep valleys and huge trees, likely typical of the former forests in that area, Graham said.

Early 19th century visitors like Clark and Irving, Graham added, encountered a landscape that already had been changed or altered, either by the indigenous peoples who had lived and traveled over it as well as the French fur traders, who trapped, farmed and built upon it.

“Most English-writing historians never saw the rich ecology and wildlife of pre-settlement times,” Graham said.

“The Missouri pioneers and state founders of the early 1800s lived in an already altered ecology. They quickly transformed the land further, and their descendants more so.”

Today state conservation staffers work with private landowners and others to preserve remnants of the state’s natural beauty that existed 200 years ago.

“They are tiny pieces compared to the larger geography, and they are places where invasive species and poor past land use sometimes challenge conservation land managers,” Graham said.

“But if Kansas Citians are willing to sometimes walk on a trail or float in watercraft on a river, they can enjoy how nature once existed in western Missouri, where American eastern hardwood forests and woodlands met the tallgrass prairie.”

Digital resources

The Missouri bicentennial boasts a robust online presence, allowing those interested to access informed interpretation online. The Missouri Bicentennial Commission website features a long list of projects and events. But there are other resources.

Missouri Digital Heritage, operated by the Missouri Secretary of State, offers access to the collections of the Missouri State Archives and the Missouri State Library.

The Kinder Institute on Constitutional Democracy at the University of Missouri and the Missouri Humanities Council also collaborated on the digital “Struggle for Statehood” digital exhibit.

In addition, Historic Missouri offers a free mobile app featuring curated walking and driving tours of historic communities and locations across the state. Students at the University of Central Missouri developed the content.

Another online exhibit, “Show Me Missouri,” developed by Diane Mutti Burke of UMKC with colleague Sandra Enriquez, assistant history professor at UMKC, will feature 200 culturally significant artifacts in the state’s history, accompanied by descriptions of the items and – in time – essays explaining their significance.

The site, scheduled to go live on the Aug. 10 bicentennial date, will be maintained by the Springfield-Greene County Library District at showmemo.org. While it will note aspects of Missouri history that are unique, difficult topics such as slavery or racial and ethnic discrimination will not be avoided, Mutti Burke said.

“We felt it was important not to just focus on Missouri’s statehood moment and not shy away from Missouri’s legacy of slavery – which is problematic and difficult – but to really engage with this complicated history,” she said.

This story was originally published on Flatland.