Kansas has managed to travel backward in pandemic time. Suddenly it’s February again.

Except this time, the state faces a version of COVID-19 that’s twice as contagious.

The delta variant is plowing through a lightly vaccinated population, and multiplying fast. In mid-June, Kansas saw hundreds of new cases a week. Now, there are thousands of new cases per week.

That’s why time really matters.

Say you get a shot of Pfizer tomorrow, then the second dose three weeks later. A couple more weeks must pass before your body has built up its arsenal of antibodies to guard you against hospitalization and death.

“Five weeks is a long time,” deputy state health officer Joan Duwve said. “That’s just a prime opportunity for this virus to find you, to make you sick and to spread to other members of your family.”

Yes, you can still catch COVID-19 after getting a vaccine, but misinformation about what that means deflects from this simple fact: For the vast majority of people, your vaccinated body will be ready for it.

“These are just heroic vaccines,” said Vaughn Cooper, who heads the Center for Evolutionary Biology and Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh. “The chief scientific achievements of my lifetime.”

Around 99% of recent coronavirus deaths in the U.S. and 97% of the hospitalizations involved people who were unvaccinated.

Each day, a few thousand Kansans get a shot of the vaccine that scientists say can stop this pandemic.

Meantime, Kansas hospitals are filling beds fast, and some are turning away seriously ill COVID patients from other areas and asking nurses to sign up for extra shifts.

The delta in Kansas

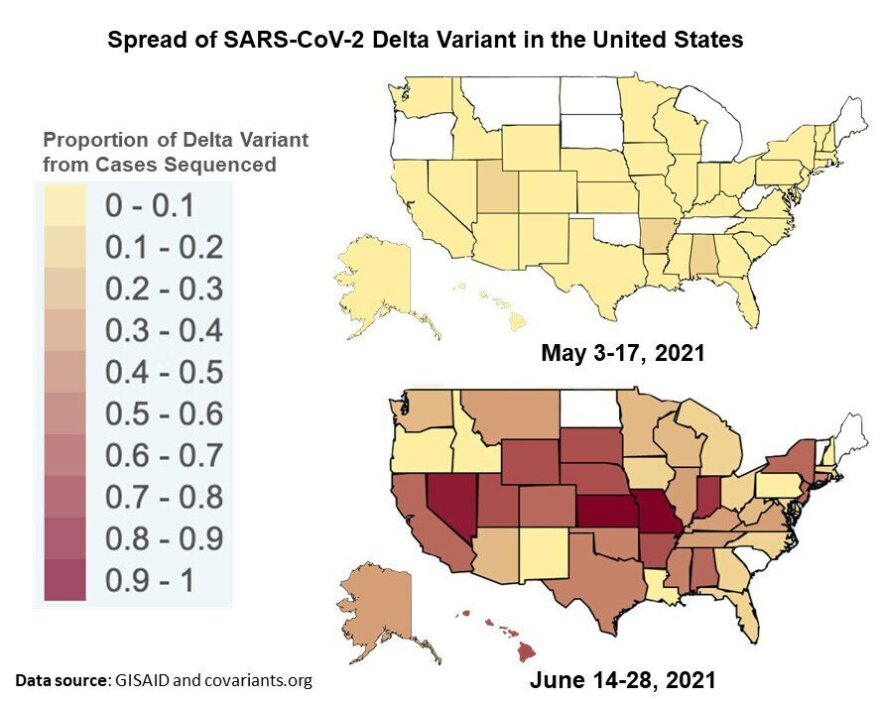

In late April, Kansas identified its first case of the delta variant. Now almost all the COVID cases here are this flavor.

Kansas sits smack dab in the delta zone, wedged between other states with the same problem — most notably, Missouri, where preventable infections are overwhelming hospitals in Springfield.

And so delta is doing what delta does best: spreading. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention lists Kansas as one of 17 states with high transmission levels right now.

Not satisfied with hugging the Missouri border, the variant has crisscrossed the state, fueling upticks around Junction City, Wichita and other areas.

On the past three Mondays, Ascension Via Christi’s St. Francis Hospital in Wichita went from 13 patients to 20 to 46.

Dr. Sam Antonios, Via Christi’s chief clinical officer, described the health system’s staff as “disheartened.”

“They obviously don't want to have to go back to the same level of severity of illness,” he said.

Ascension built up significant stores of protective garb, testing gear and other supplies in the wake of last year’s shortages.

“What will continue to be the challenge is getting all the right staff in the right places,” he said. “We’re bringing in extra staff where we can and where we need to. However, it would be better for us to not have to do any of that.”

And that’s possible, scientists say, if people lean on the same tools that helped combat other varieties of COVID-19.

You’ve heard it before. It matters again. Wearing masks. Social distancing. Limiting gatherings to outdoors or well-ventilated spaces. Getting the vaccine. Going for a free coronavirus test if you have so much as the sniffles.

The big question

How bad will it get in Kansas?

Could it get as bad as last December, when daily COVID inpatients topped 1,000 and desperate hospitals spent hours calling each other in search of a free bed, only to send critically ill patients hours by ambulance out of state to Omaha or whatever other Midwest city had a free spot that day?

Experts lean toward “no,” but with significant caveats.

The good news: 80% of the state’s residents 65 years and older got vaccinated. That group faced the biggest risks from COVID-19. So with far fewer older people landing in the hospital, the hope is to avoid running out of beds like last winter.

But the other 20% of people over the age of 65 who didn’t get vaccinated are still a lot of people.

And on the whole, less than half the state’s population got the shots. In many counties, less than a third.

That’s not enough to keep such a swift moving variant in check, as Springfield shows.

“We don’t, unfortunately, have high enough vaccination in Kansas or Missouri” to slow the spread, said Amber D’Souza, a professor of epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. “It’s going to have to be preventive measures — distancing and behavioral changes.”

Delta “is just a harder battle,” she said. “Because it is spreading to more people each time someone is infected.”

The new variant generates far more copies of itself in a person, which helps it reach the next one. Even a vaccinated person with little in the way of symptoms could pass the germs along to an unvaccinated friend, who then gets very ill.

So while the U.S. as a whole shouldn’t see inpatient numbers and deaths spike as high as last winter, experts like D’Souza warn that some parts of the country could get clobbered just as bad this fall.

Last winter, the U.S. was racking up more than 200,000 new confirmed infections a day, which fell to around 10,000 earlier this summer. With the advent of delta, the country is back to reporting more than 60,000 a day.

In the past 3 weeks as Delta progressed to dominance in the US (now ~80%), covid hospitalizations increased from their pandemic nadir, 15,000, to today over 25,000, a 67% jumphttps://t.co/xStmHRzwg2 pic.twitter.com/5vG7DsG06q

— Eric Topol (@EricTopol) July 19, 2021

Kansas confirmed nearly 4,000 new cases last week and daily inpatient numbers have climbed back to nearly 400. The state hasn’t seen figures like that since February.

“It is scary,” said Duwve, from the state health department.

So what happens next?

“That story has yet to be written,” she said. “Because we as individuals have a lot of control over our behavior, and we know that there are things we can do to prevent the ongoing spread.”

The school debate

Schools face a tough decision for that reason: whether to make students mask up when classes restart in a few weeks.

“The safest thing to do is to wear masks all the time,” D’Souza said. “But there's a cost for that. For everyone's comfort, right?”

The ideal, she said, is for school districts to set a threshold. When the case rate in their area hits that number, it’s time to put on the masks.

But some school districts might find it difficult to communicate that plan to the public, she said.

So if superintendents have to make a call in August and stick with it, then they’ve got to look at the outlook now.

Apparently, Kansas City doctors think the situation is bad enough to warrant masking up.

Last week, 100 of them signed an open letter begging schools to have unvaccinated students and teachers wear masks this fall.

So far just one major Kansas school district — Kansas City, Kansas — has agreed.

Celia Llopis-Jepsen reports on consumer health for the Kansas News Service. You can follow her on Twitter @celia_LJ or email her at celia (at) kcur (dot) org.

The Kansas News Service is a collaboration of KCUR, Kansas Public Radio, KMUW and High Plains Public Radio focused on health, the social determinants of health and their connection to public policy. Kansas News Service stories and photos may be republished by news media at no cost with proper attribution and a link to ksnewsservice.org.