Instant cups of soup — the kind that often come in a Styrofoam cup full of noodles — send children to the hospital every day.

"I don't have them in my house," says Dr. Warren Garner, director of the burn unit at University of Southern California's County Hospital in Los Angeles. "I would say that we see at least two to three patients a week who've been injured by these products."

These soups are dangerous because of the way the cups are designed. The cups are tall, lightweight, and have an unstable base that makes them tip over easily. At Garner's unit, the most common cases are small children, often toddlers, accidentally tipping the cup over on to themselves.

"It pulls down on top of them," Garner says. "The hot liquid then burns their chest, arms, torso, sometimes their privates, occasionally their legs." He says there's no other injury that he sees as regularly that can be so directly attributed to a product's design, and calls these soups "uniquely troublesome."

Through calls to a dozen burn units at hospitals across the country, we learned that this is a common phenomenon, with children being the most frequent victims. Eight of the 12 hospitals said they see the injury several times a week. One hospital located in Washington D.C. says they regularly see 5-6 patients a week with the injury, especially during the colder months.

Noodle soup is strangely perfect for delivering a serious burn. The sticky noodles cling to the skin, which leads to deeper, more severe burns, according to a study published in 2007. The study showed that hospital stays for upper body noodle-soup burns are more than twice as long as scalds from hot liquids alone. Garner says that about one in five children he sees with the burns end up needing surgery, and these patients can face permanent scarring and limited mobility in their joints.

But not all noodle soup cups are equally dangerous. To illustrate this point, I visited an Asian grocery store with Dr. David Greenhalgh, Chief of Burns at Shriner's Hospital for Children in Northern California, and the author of a study entitled "Instant Cup of Soup: Design Flaws Increase Risk of Burns." He swats at eight brands, and describes how some containers tip more easily than others.

"Seems like we get a scald burn and [we'd say], 'Well, what's this from? Oh, another cup of noodles soup,'" says Greenhalgh, describing his experience at Shriner's. "It just came to me. It was like, 'Wow, it's a very simple test. Can you knock over one kind of cup more than another?'"

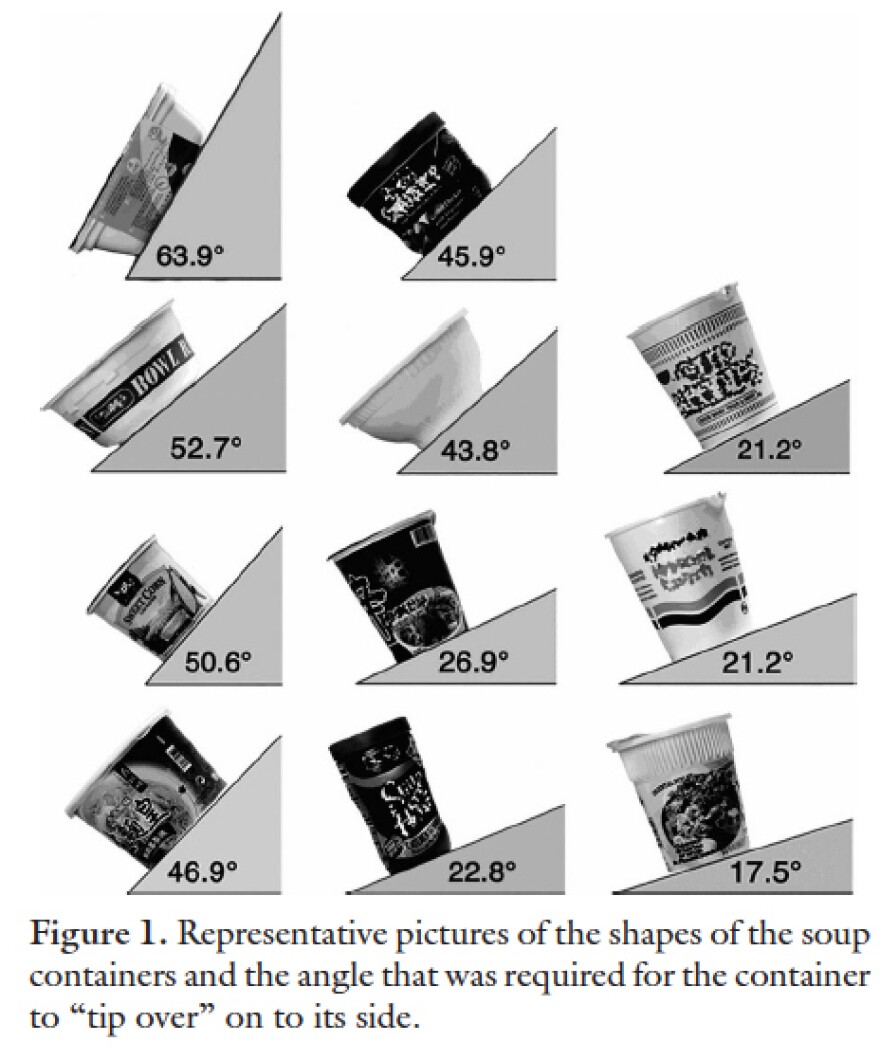

That was the study's question. To test it, the study authors went to they grocery store and bought 11 brands of soup manufactured all over the world and calculated the angle at which the soup tipped over and spilled. Not surprisingly, tall cups with a narrow bottom tip over about three times more easily than short, squat containers with a wide, stable base. ( Here's the study.)

Cup Noodles by Nissin is one of the most prone-to-tip brands in Greenhalgh's study. It is also one of the cheapest and most popular. Nissin invented the product forty years ago, and has sold more than 25 billion worldwide. Cup Noodles spills at 22 degrees. Compare that to the best performer, a brand called Nicecook, which has a shallow, squat container. You need to turn Nicecook almost vertical-- 64 degrees-- before it tips over.

Greenhalgh says this problem might have an elegant and potentially low-cost solution. Imagine a Yoplait yogurt container-- skinny on top and wide on the bottom. In other words, just invert the design of the cup.

"All you have to do is flip it over," says Greenhalgh. "It would seem to be a very easy thing to do and think I could get some of my team members to go to one of the companies and say, 'Here why don't you try this?'"

I reached out to Nissin and manufacturers of some of the other "tippiest" cups in Greenhalgh's study. Every company declined to comment or failed to get back to me. Greenhalgh calculates that his simple change-- inverting the design of the cup-- would make Cup Noodles almost three times less likely to tip, comparable to the safest brand in his study.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.