Linguist David Crystal describes English as a "vacuum cleaner of a language." Speakers merrily swipe some words from other languages, adopt others because they're cool or sound classy, and simply make up other terms.

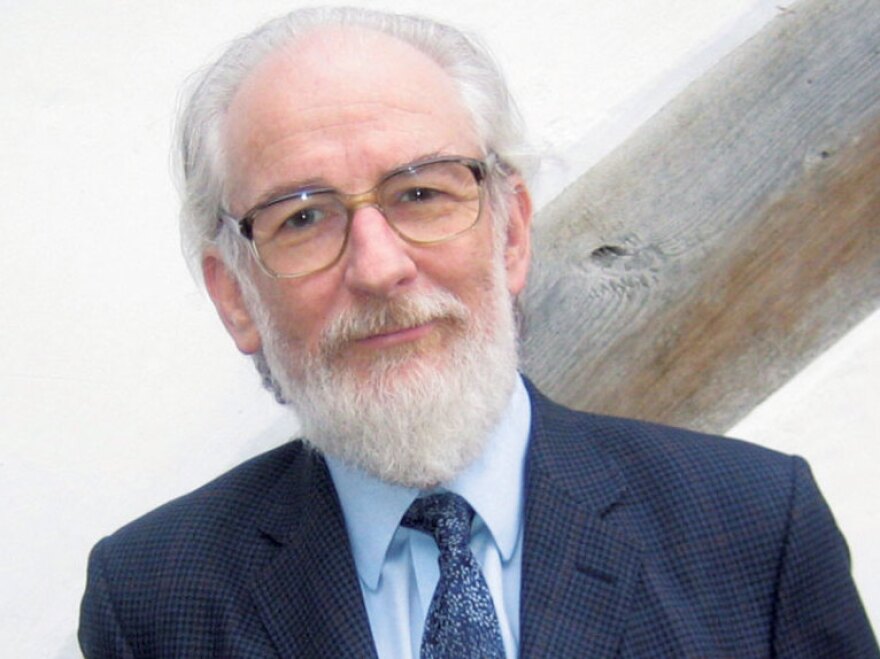

In his new book, he tells The Story of English in 100 Words, using a collection of words — classic ones like "tea" and new words like "app" — that explain how the the English language has evolved.

Crystal thinks every word has a story to tell, even the ones as commonplace as "and."

"Poor little words like 'and,' and 'the,' and 'of' ... they don't get any press at all," Crystal tells NPR's Neal Conan. "And this is a great shame, because without them, we have no syntax. We have no grammar. The whole language falls apart."

Crystal discusses the idiosyncrasies of the English language and some of his favorite words that made the list.

Interview Highlights

On the English language as a vacuum cleaner

"English has been this vacuum cleaner of a language, because of its history meeting up with the Romans and then the Danes, the Vikings and then the French and then the Renaissance with all the Latin and Greek and Hebrew in the background.

"Every language that English has come into contact with, it's pinched some of the words — thousands and thousands of words in many cases. And something like 600 languages have loaned or given words to English over the past 1,000 years."

On the origins of 'OK'

"One of the reasons why I love it is because of the point that Roger has made, and that is that it has had so many guesses for its origins. I stopped counting at 50.

"I think we do now know where OK comes from. There was a great American lexicographer called Allen Walker Read, who many years ago did a huge study and found out that the word 'OK' first appeared in the 1830s ... in a newspaper in Boston. Because at the time, there was a vogue for inventing humorous abbreviations using initial letters.

"And OK came, at that point in time, from 'oll korrect,' ... O-L-L for 'all,' and K-O-R-R-E-C-T for 'correct.' Now, there were dozens of other abbreviations in the Boston newspaper at the time, and most of them had disappeared. But this one didn't. OK stayed. And the reason is it had a completely fresh boost of life the following year, when it began to be used as a slogan in the U.S. elections in 1840."

On the origins of 'blurb'

"Nobody exactly knows when a particular word comes into English.

"But in the case of blurb, we do, because this is a perfect example, been well recorded. The American humorist Gelett Burgess, back in ... 1906, '07 ... he was at a dinner and he was advertising a book. And he drew a little picture on the jacket of the book that was being circulated and called it a 'blurb.' I mean just like that. I mean, he invented the word there and then. And it caught on.

"It became part of the publicity for the book. Ever since then, the stuff that you read on the back of a book, which advertises its great properties, are called blurbs. So you can actually pinpoint that particular word down to a particular day, even, a particular moment in linguistic history. And that's very rare indeed."

On deciding how to end the book

"I'd love to put in ... the latest word in the English language. And, of course, there's no such thing because as soon as you put that in a book, it's out of date because another word is going to come into use tomorrow. So I thought, what is a word that will point us towards the future? ...

"So I focused on Twitter, which, at the time I was writing, was ... still developing as one of the latest and coolest developments online. And I suddenly realized there was a huge family of words out there that Twitter had begun to generate. I've collected, over the months since it started, something like a thousand words, all based on Twitter in some shape or form.

"So you've got ... not just Twittering and tweeting and so on. You've got the Twittersphere, which is the word I use in the book to capture all this. You've got, for people who tweet too much, they're suffering from Twittoria ... We've got a Twidiction here. You can look all these things up in the Twictionary."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.