I guess everybody, even the smartest people who ever lived, have days when they feel dumb — really, really dumb. Oct. 1, 1861, was that kind of day for Charles Darwin.

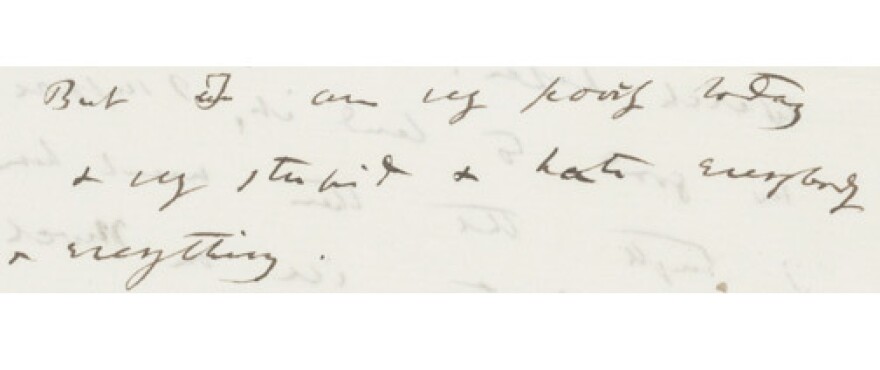

In a letter to his friend Charles Lyell, Darwin says, "I am very poorly today," and then — and I want you to see this exactly as he wrote it, so you know this isn't a fake; it comes from the library of the American Philosophical Society, courtesy of their librarian Charles Greifenstein. Can you read it?

It says:

Whoah! You know the feeling, right?

But this is Charles Darwin writing in 1861, two years afterhe'd published On the Origin of Species. His years of labor (which "half-killed me," he said) were behind him. He was famous now, already working on his next book, which was going to be about orchids.

Does he mention orchids in this letter?

He does.

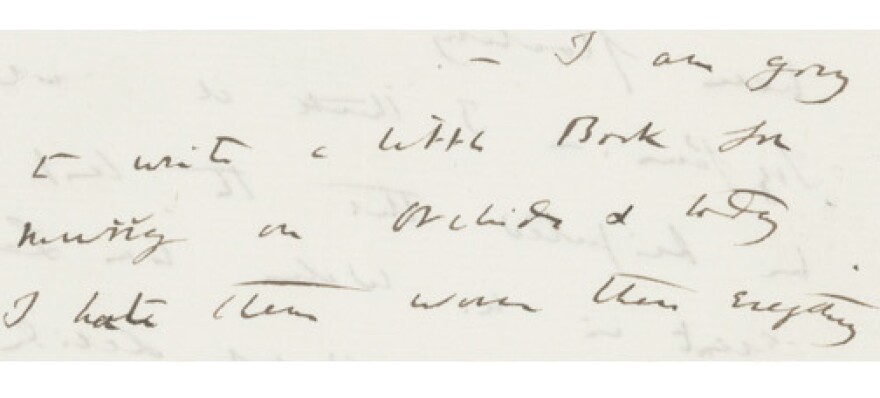

"I am going to write a little Book for Murray on orchids," he says, [the italics that follow are mine] and today I hate them worse than everything."

Here's the line. Read it yourself:

Who knew that minds of the first rank wake up some days feeling like they belong in a sewer? In his short biography of Darwin, David Quammen writes that he was "nerdy, systematic, prone to anxiety." He was not quick, witty, or social. He spent decades working out his ideas, slowly, mostly by himself, writing letters and tending to a weak heart and a constantly upset stomach. He was a Slow Processor, who soaked in the data, thought, stared, tried to make sense of what he was seeing, hoping for a breakthrough. All around were snappier brains, busy being dazzling, but not Darwin's, which just plodded on until it finally saw something special, hiding in plain view.

But most days, I guess, were hard. "One lives only to make blunders," he writes here to Lyell.

Blunder, Blunder, Blunder

I feel bad for Mr. Darwin, but, honestly, seeing this letter made me happy. I shouldn't feel this way, I know, but if a world-changer like Darwin felt like this, if even he had jolts of hating "everyone and everybody," that reminds me no one's exempt ... and that's nice.

Plus, suddenly there are two Darwins in my head instead of one. There's Classic Charles, of course, the wise old genius. And now there's Self-Hating Charles, a guy I could have a beer with.

I like variety in my Darwins.

Thanks to Charles Greifenstein, associate librarian and curator of manuscripts at the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, for help in getting an image of Darwin's letter, and to Maria Popova, whose blog, Brainpickings, got me thinking about this; Also, David Quammen's classy little book about Darwin is called The Reluctant Mr. Darwin, and, of course, thanks to my illustrator on this post, Aaron Birk — who got my call as he was stepping out to do something more important, and still managed to produce Grumpy Darwin. His forthcoming book is a sequel to his already lovely graphic novel, The Pollinator's Corridor .

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.