Photographers "searched their attics, basements and hard drives, looking for photographs that they have always liked, but for one reason or another, have gone unpublished and/or unnoticed. Each chose a single image to rescue from oblivion."

That's how Magnum describes the selection process for the photos in its Magnum Square Print Sale. Small, signed prints by the members of this international photographic cooperative will be available for $100 each until 5 p.m. ET on Friday, Nov. 14.

Goats and Soda asked British photographer to discuss the image he selected. He has been a member of Magnum for over 25 years. He has also completed more than 20 assignments for National Geographic magazine, including one that led him to India for the annual Jaipur Kite Festival, where he went in the winter of 1999-2000 to shoot a feature on the new millennium. The idea was to celebrate elements of the earth: fire, water or air.

"I had the idea that one way to express the air was the kite festival," Franklin says. "I couldn't count the number of people who had kites flying up in the sky from the roofs. Nobody seemed to be excluded at all."

Why did such an iconic-looking photograph — with a red heart-shaped kite — go unnoticed and be put away in a box? "It's quite common," he says. "There are so many pictures and you edit them and they go into a pile and they go into the archive, and you move onto something else."

It was only 15 years later that he came back to it and thought, "Oh, that's sweet. I really like that picture."

The kite festival was vast, he recalls, including everything from "fancy fighting kites" to "the shabbiest little things made out of bits of paper and a bit of string."

But the heart-shaped kite was special. For Franklin, "There's a lot of love everywhere, even in areas where there is a lot of challenge and a lot of poverty." That love, he says, "transcends everything."

Suffering, he says, "is everywhere, but there is suffering in different types of ways. There is certainly less material wealth in India than in the United States and in Europe, but there is a lot of spiritual wealth and there are a lot of other kinds of wealth that perhaps we don't have. So when you kind of weigh out the balance of wealths, they are just as wealthy as anybody else."

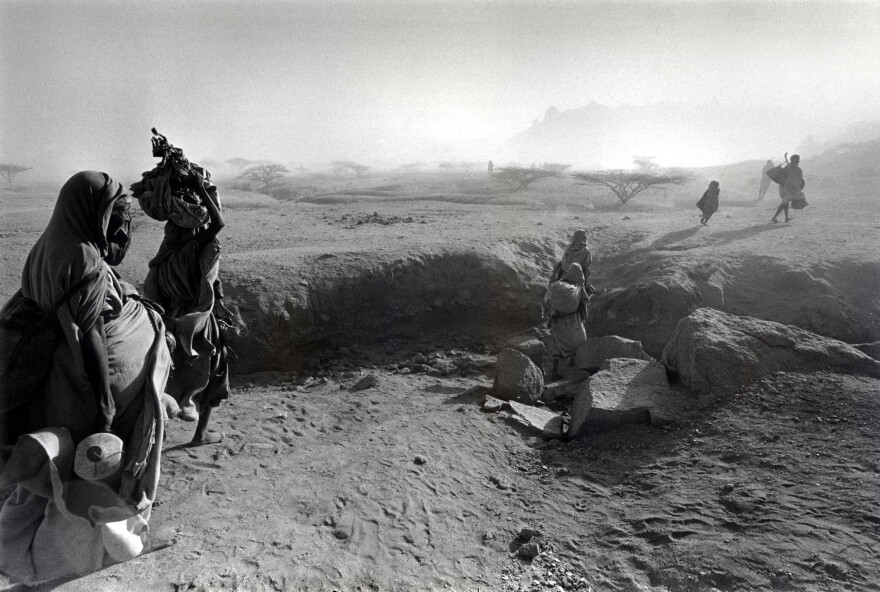

Although Franklin has recently devoted himself to long-term projects concerning the environment, a series of assignments in the 1980s landed him in Sudan, where he documented famine for Time magazine. He stayed in a flat in Khartoum with the Brazilian photographer Sebastiao Salgado, who was working on a book.

"That's how I joined Magnum. He [Salgado] recommended me," Franklin recalls. "Every day we would go off to these refugee camps." For his weekly magazine assignments, Franklin had to send rolls of film back to Paris. "You weren't wiring pictures then," he says.

We asked him for an "orphaned photograph" from this series, too.

"They're not orphaned," he reminds us. "They have an author."

As for the photo he selected:

"All I know is I have one picture from that series hanging up in my house. So it's obviously survived the test of time. And it's just a picture of a few people walking across plains with just a few things they own on their backs. That sense of dislocation, the sense of people without anything, or anything to go back to: If you think about it, even for a few seconds, it's a horrifying thought. Imagine yourself in that situation. Walk away from everything you have, or everything you've grown up with and bundle it into a sheet in 20 minutes. What would you take? How awful would that be?

"On the one hand, you can think of it as an image. On the other hand, you have to think about it as a part of somebody's life and a very tragic part of somebody's life, and replicate it several thousand times in this particular case."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.