We've been telling you about the opposition from some writers to the decision by the PEN American Center to give Charlie Hebdo its Freedom of Expression Courage Award. The satirical French publication was targeted by Islamist militants Jan. 7 apparently for its cartoons of Islam's Prophet Muhammad. The attack killed 12 people.

"There is a critical difference between staunchly supporting expression that violates the acceptable — and enthusiastically rewarding such expression," more than 180 writers said in their letter of protest.

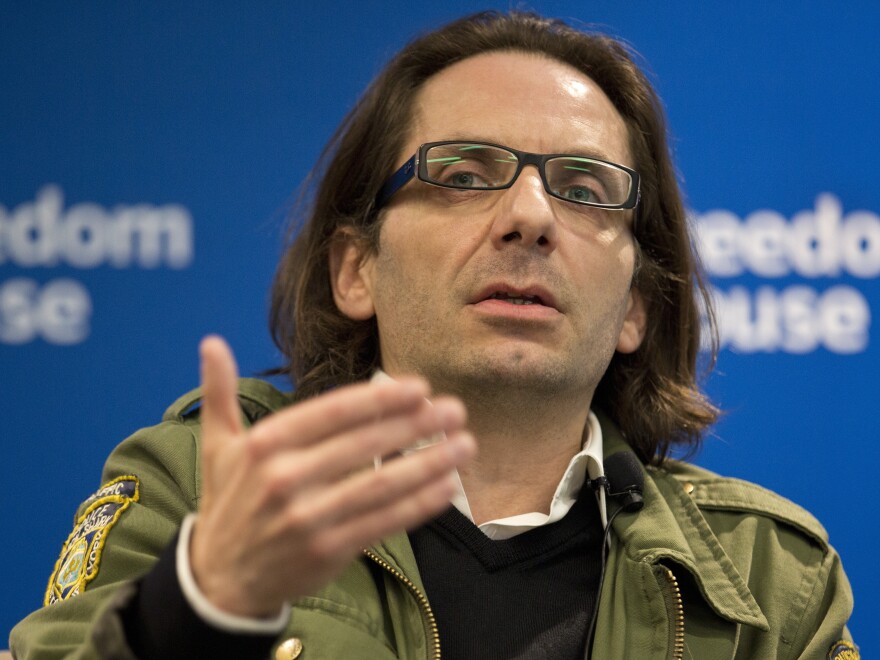

In particular, they criticized Charlie Hebdo's cartoons of Muhammad, saying the drawings were intended to "cause further humiliation and suffering" to a victimized population. But Jean-Baptiste Thoret, a film critic for the magazine, who is accepting the PEN award in New York on Tuesday, told NPR that stand is seemingly contradictory.

"I have to say that if you're standing for the freedom of expression, you can't be at one moment for this freedom of expression, and two or three minutes later, against that," he told NPR's Melissa Block. "You know, you're honoring a principle. You're not honoring a specific content in a magazine. Even in Charlie Hebdo," we did not often agree.

Thoret said much of the criticism directed at the magazine appears to come from those who "don't really know what they are talking about." He said the magazine never attacked Muslims. What it did do, he said, was sometimes satirize religion.

"Nothing is sacred for us," he said. "That's something that is very important."

It's also important to note here that Charlie Hebdohad a long tradition of lampooning figures from business, politics and religion. But it was its cartoons of Muhammad that it first printed in 2005 that got the most attention. Many Muslims consider any depiction of their prophet — even positive ones — to be blasphemous. Charlie Hebdo was firebombed in 2011 and received death threats over the years that culminated in the Jan. 7 attack that resulted in the deaths of some of its best-known cartoonists and staff members.

The attacks led to a global outpouring of support for the magazine — and defenders adopting the slogan "Je suis Charlie" [I am Charlie]. Thoret told Melissa that the slogan's popularity is ironic.

"Before Jan. 7, very few people were Je suis Charlie at that time; so the irony is that today everybody is Je Suis Charlie, of course," he said. "We are all OK with that. We are all against terrorism. But maybe it would have been more useful 10 years ago. At that moment, we [were] very alone. So for me it's part of that irony. Everybody is Je suis Charlie, but ... maybe it's too late."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.