They were under watch by the FBI and the New York Police Department. And by the early 1970s, the Young Lords emerged as one of the country's most prominent radical groups led by Latino activists.

Inspired by the Black Panthers, a band of young Puerto Ricans wanted to form a Latino counterpart to the black nationalist group. In fact, one of the founding Young Lords in New York City almost started a group called the "Brown Tigers."

Instead, in the summer of 1969, they formed the New York chapter of a Chicago gang called the Young Lords, put on purple berets and hit the streets.

"In many ways, they gave the Puerto Rican community a big coming-out party in the city," says Johanna Fernández, a history professor at Baruch College, who's writing a book on the Young Lords.

Fernández is also one of the curators of a new exhibition about the group on display at the Bronx Museum of the Arts, as well as El Museo del Barrio and Loisiada Inc., a cultural center in New York City. (The Loisiada exhibition is set to open on Thursday.)

"Part of what the Young Lords bring to the history of the civil rights and black power era is a perspective that illustrates the condition of oppression and racism experienced by other minority groups," she says.

The Young Lords included African-Americans as well as Dominicans and other Latinos. But many were the children of migrants from Puerto Rico.

All faced high unemployment, police brutality and drug abuse in some of New York's poorest neighborhoods in the 1960s and '70s.

Former member Juan González recalled in the 1996 documentary !Palante, Siempre Palante!:

We all had a tremendous sense that our people did not deserve the kind of situation and the kind of condition that we were living under, that our parents had worked just as hard as anyone else to make a better life for us. And for some reason, we weren't succeeding. So we had that commitment that we were going to change things. And it didn't matter what had to be done, but we were going to change things.

The Young Lords in New York eventually broke off ties with the Chicago group. For their first campaign in Spanish Harlem, the Young Lords swept sidewalks, piled trash into the middle of the street and set it on fire. That's how they got city officials to improve trash collection.

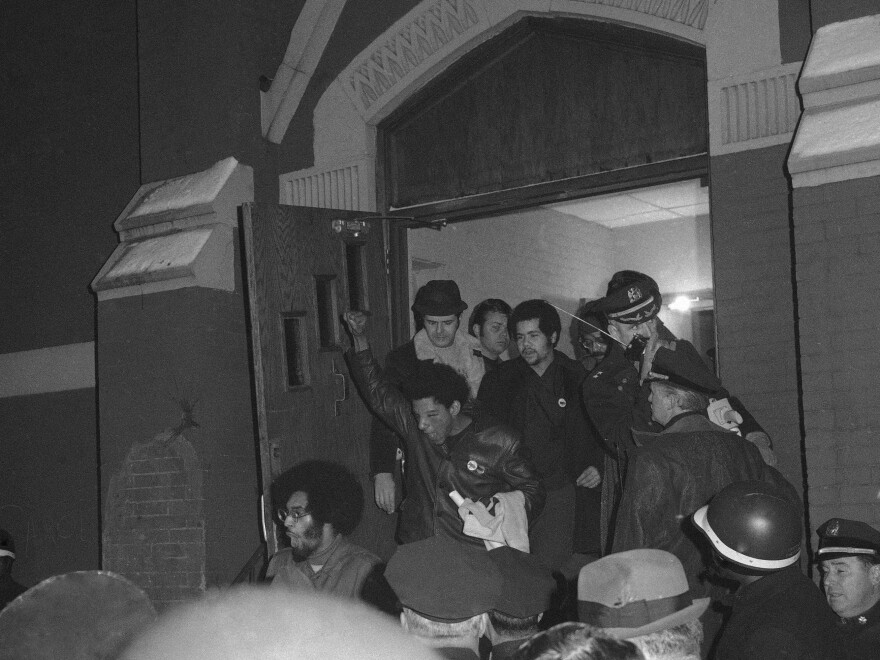

Later, they took over a church to run a free breakfast program for children, and co-founder Felipe Luciano held a press conference outside.

"This is going to happen to any institution in any oppressed community that does not respond to the needs of the people!" he said. The crowd around him cheered, "Right on!"

At the Bronx Museum's exhibition, black-and-white photos from street protests hang across from a wall of pages from the group's bilingual newspaper.

"There was no YouTube. There was no Twitter. So the paper was the backbone of the organization," recalls Denise Oliver-Velez, the first woman elected to the Young Lords' central committee. "We not only communicated with it, but we also financed ourselves on sales of the newspaper everyday."

The Young Lords were also on the radio every week to talk about topics like racism, Marxism and gender equality.

Their calls for the independence of Puerto Rico from the U.S. drew the attention of the FBI's Counterintelligence Program.

"The Young Lords, like Martin Luther King and Malcolm X and the Black Panthers, were the subject of investigation," says Fernández. "And there was a conscious attempt to disrupt and undermine the activism of the organization."

By the mid-1970s, infighting and disagreement over the Young Lords' mission led to their downfall. Eventually, some of its veterans funneled their activism to teach at colleges or work in government and in the media.

Gloria Rodriguez, who joined the Young Lords when she was 18, now teaches at Bronx Community College and runs a women's community center. She says the group helped forge a model of Latino activism and fearlessness.

"The fearlessness was fueled by a very strong commitment to making a better life, a better world and a better existence for our people," she says.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.