We want to cut through the spin with a new feature we're calling "Break It Down."

Break It Down is going to be a regular part of our campaign coverage. We're going to try some new things. It might read a little differently from time to time. But our goal is to zoom in on what the candidates are saying, and give you the factual breakdown you need to make a sound judgment.

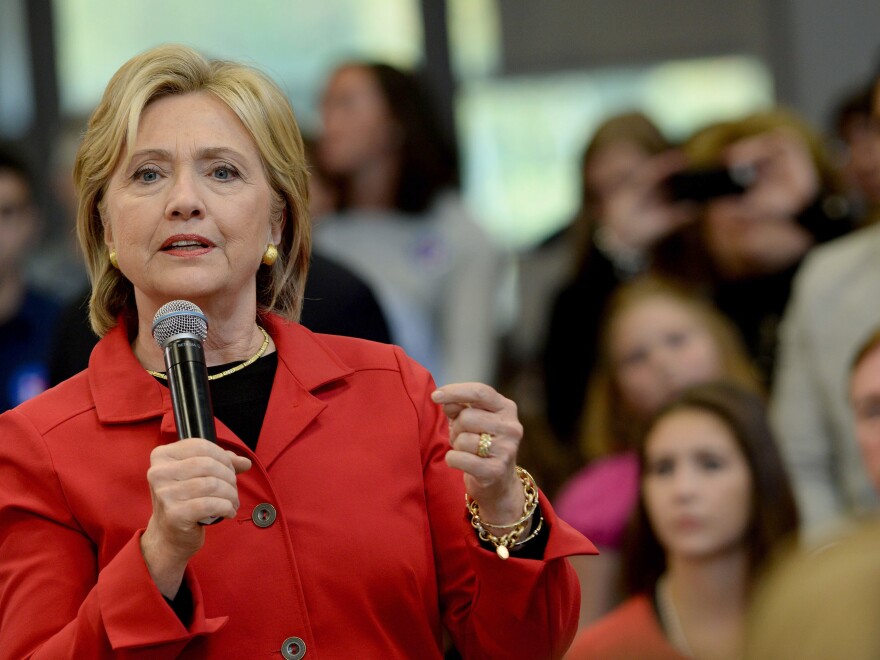

Hillary Clinton seemed to be barely holding back tears at a town hall in New Hampshire on Monday. Speaking in the aftermath of another tragic mass shooting, this time at an Oregon community college, the Democratic presidential candidate pitched her gun control proposals.

In the middle of her remarks, she made a big claim: She said that gun-makers and sellers are "the only business in America that is totally free of liability for their behavior." We decided to see what she was talking about — and whether she's right.

Let's Break It Down.

The Claim:

"So far as I know, the gun industry and gun sellers are the only business in America that is totally free of liability for their behavior. Nobody else is given that immunity. And that just illustrates the extremism that has taken over this debate."

The Big Question:

Is Clinton right that the gun industry enjoys legal protections that other industries don't?

The Long Answer:

Clinton is wrong that gun companies have zero liability for their goods, but they do have special legal protections against liability that very few other industries enjoy.

To see what she's getting at, you have to back up 10 years. Clinton is talking about a 2005 law called the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act, or PLCAA — a law she wants to repeal as part of her gun control proposals.

Lawmakers passed that law in response to a spate of lawsuits that cities filed against the gun industry in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Those lawsuits often claimed gun-makers or sellers were engaging in "negligent marketing" or creating a "public nuisance."

In 2000, for example, New York City joined 30 counties and cities in suing gun manufacturers, saying manufacturers should have been making their products safer and also better tracking where their products were sold. Manufacturers, one argument at the time went, should stop supplying stores that sell a lot of guns that end up being used in crimes.

In response to these lawsuits, the NRA pushed for the law, which passed in 2005 with support from both Republicans and Democrats. Then-Sen. Clinton voted against it; her current Democratic opponent, Bernie Sanders, voted for it.

The law, however, allows for specific cases in which dealers and manufacturers can be held responsible. So that makes Clinton's statement technically incorrect.

"[Clinton's statement] doesn't appear to be completely accurate," said Adam Winkler, professor of law at UCLA and author of Gunfight: The Battle Over the Right to Bear Arms in America, in an email to NPR. "The 2005 law does not prevent gun makers from being held liable for defects in their design. Like car makers, gun makers can be sued for selling a defective product. The problem is that gun violence victims often want to hold gun makers liable for the criminal misuse of a properly functioning product."

In other words: If you aim and fire a gun at an attacker, it's doing what it was intended to do. If it explodes while you shoot and hurts you, though, then you can sue the manufacturer. Likewise, if you had told the gun-store owner you planned to commit a crime with that gun, your victim could potentially sue.

However, Clinton "is not totally off base," said John Goldberg, a professor at Harvard Law School and specialist in tort law. He said Congress was particularly "aggressive" in granting the gun industry this legal shield.

"Congress has rarely acted to bar the adoption by courts of particular theories of liability against a particular class of potential defendants, especially when that form of liability has not yet been recognized by the courts," he said.

At the time that the law passed, the NRA argued that the industry needed the protection, because — unlike carmakers, for example — it did not have the "deep pockets" necessary to fight a slew of lawsuits, as the New York Times reported.

Gun-rights advocates have also argued that suing a gun company for crimes committed with its products is akin to suing a car company for drunken-driving fatalities.

But the issues at hand are more complex, say some legal scholars.

"It's more like — are you a bartender and do you keep on pouring drinks for someone?" as Fordham University law professor Saul Cornell told NPR. That might be a better way to think about whether manufacturers shouldn't supply certain stores, he says.

For an example of how this plays out, look at Adames v. Beretta. In this case, a 13-year-old boy removed the clip from his father's Beretta handgun, believing that made the gun safe, and then accidentally shot his 13-year-old friend. The victim's family sued Beretta, saying the company could have made the pistol safer and provided more warnings, according to SCOTUSBlog. Citing the PLCAA, the Illinois Supreme Court dismissed Adames' claims, and the U.S. Supreme Court ultimately refused to hear the case.

Victims of gun crimes like the Adames family may or may not have good cases, but PLCAA opponents say plaintiffs should at least be heard in court.

The Broader Context:

Clinton wants to repeal PLCAA as part of her broader gun control agenda, which also includes proposals to close the "gun-show loophole" and prevent domestic abusers from obtaining guns.

The law is one of several recent NRA legislative victories that gun control advocates would like to roll back. Recent laws have also stopped Centers for Disease Control and Prevention research on firearms, and they've also stopped researchers from accessing gun trace information, as NPR's Carrie Johnson has reported. Gun-rights advocates say withholding that trace information is about maintaining gun owners' privacy.

At first glance, taking a stand one way or the other on gun control means alienating a big chunk of voters. Democrats have steadily, overwhelmingly, favored gun control over the years, while Republicans have grown increasingly in favor of gun rights in the past decade or so, according to the Pew Research Center.

But then again, getting specific on gun policy might be good for Clinton in two ways. One is that it could endear her to pro-gun-control Democrats (this is one of the few areas where she is to the left of Sanders, her closest Democratic competition), particularly as calls for tougher gun control have grown louder after a long string of mass shootings.

Two, research has also shown that while Americans tend to be in favor of "gun rights" broadly, they also tend to favor specific potential gun control regulations, like background checks or assault weapon bans.

The Short Answer:

Clinton is wrong that gun manufacturers have no liability for their products, but she's right that they have unique protections from lawsuits that most other businesses — and particularly consumer product-makers — do not.

Sources:

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.