When it's time for medical care, where do you go? The doctor's office? An urgent care clinic? Or the nearest hospital?

As many as 1 in 3 Americans sought care in an ER in the past two years, according to a recent poll by NPR, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health. That relatively high frequency may be a matter of convenience, even though many in the poll also report frustration with the cost and quality of care they received in an ER.

Skipper Beck, for instance, who lives in Holiday, Fla., near Tampa, wasn't crazy about the care he got. As he remembers it, he was having a great Friday, playing beach football on Florida's Gulf Coast, when he hurt himself.

"I hit someone a little too hard, a little bit too low," says Beck, who is 36 years old.

By that evening, Beck couldn't rotate his shoulder. It was painful to lift any weight, he says. He thought maybe he'd dislocated the shoulder, fractured it, or maybe torn something. So, late that night, he headed to the ER.

The medical staff ran tests, put him in a sling and sent him on his way – 4 1/2 hours later. "Honesty I felt like cattle," he says. "Kind of 'get me in, get me out.' "

Beck thinks the cost for his ER visit was unreasonable, and he felt like the doctors didn't care about him. In fact, about a quarter of the people NPR polled in Florida say the ER care they got was fair or poor, and only a third say it was excellent.

The relatively high cost and no-frills treatment in traditional emergency departments may be because most ERs are designed to treat life or death emergencies — gunshots, a heart attack, a bad car accident.

But 47 percent of recent patients in the U.S. say they seek care in an ER for non-urgent reasons. They go because it's convenient, says, Robert Blendon, a professor of health policy and political analysis at Harvard's T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Many (28 percent) say their main reason for choosing an ER for treatment, instead of a doctor's office, urgent care facility or community health clinic was because the other facilities weren't open, or the poll respondent couldn't get an appointment. About 3 percent nationally — and 8 percent in Florida — say they mainly chose an ER for treatment because the other facilities were too far away.

"Almost a third of people in Florida have used an ER in the last two years," Blendon says.

Many people assume that the only patients who choose an ER for care that's not an emergency are poor and uninsured, and don't have a regular doctor. But Blendon says that's an oversimplification: In fact, more than 80 percent of Floridians polled who used an ER are covered by health insurance.

What can be done to shift more of the non-urgent cases out of the ER?

It would help, Blendon says, if the medical world were more responsive to the problem. For instance, more community doctors could hold some office hours on evenings or weekends, so they could potentially see a patient like Skipper Beck late on a Friday, or see patients on short notice when they're sick.

"I'm hoping we'll change a bit of the discussion," he says. "You have to have a place to go, and the hours have to reflect the life of people."

But ERs are important to hospital revenue, and people seek help there for many reasons. So some hospitals are trying to make the ER experience more convenient for patients. Some emergency departments now allow patients to schedule appointments, for instance. And others modify their care and facilities to attract a particular subset of the community — such as the parents of sick or hurt children.

Delilah Torres, whose 10-year-old son, Ryan, has Down syndrome, appreciates that sort of special attention to kids.

"There were many times, many times in the past when I waited before taking Ryan to the emergency room because I knew how stressful it is to sit at the waiting room for hours," she says.

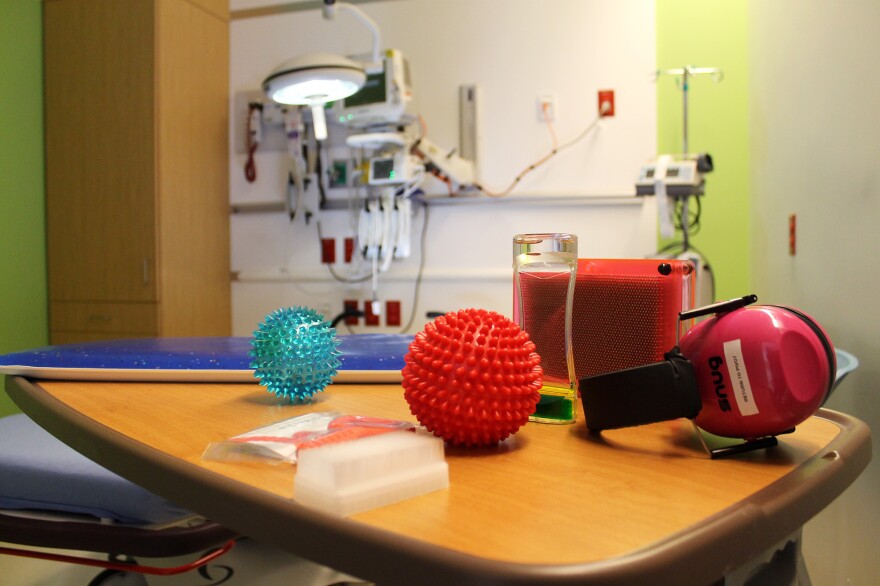

A few weeks ago, Torres had a very different experience at Nemours Children's Hospital in Orlando, Fla. When she and her son arrived in the ER, she says, the staff brought Ryan into a special room, with soothing music and toys, and talked to his mother about what upsets him.

Torres says Ryan is strong, and four nurses are usually needed to draw blood from him, or put in an IV line.

"This time was the first time it actually only took two nurses to put a line in Ryan," she says.

The Nemours Children's Hospital, in central Florida, is just a few years old. Its waiting room is painted in bright colors, and has round, plushy cubby holes cut into the wall for fun seating for the kids. Free slushies are available in the ER.

Cara Harwell, a nurse practitioner there, points out a sign that says REACH: Respecting Each Awesome Child Here.

"We want the parents to self-identify that they have a child with autism or a similar condition, like a sensory processing disorder or a mental health disorder," Harwell says.

That friendly approach in the ER will help the hospital's "patient satisfaction scores," she says. Funding is partly tied to performance in those rankings, and hospital officials are studying how it affects other aspects of care.

"Before we even put our hands on them, if we can know what the child likes and doesn't like, we can prevent them from becoming ... agitated [and from hurting] themselves or someone else," Harwell says. "We can also reduce the use of sedatives or restraints."

Of course, hospitals have yet another motivation to improve a patient's experience of the ER visit: A well-run emergency room can be profitable, and parents like Delilah Torres will drive 30 minutes past another hospital to get to one that better meets her needs.

Copyright 2020 WMFE. To see more, visit WMFE.