There's been lots of chatter on social media and among pundits, warning that the treatment of immigrant kids and English language learners is going to "get worse" under a Donald Trump presidency.

Some people on Twitter are even monitoring incidents in which Latino students in particular have been targeted.

But I wonder: When were these students not targeted? When did immigrant students and their families ever have it easy?

People are often surprised to hear that many of these children, with brown skin and "foreign-sounding" names, are U.S. citizens by birth. Yet 95 percent of Latino students in U.S. public schools are American citizens, according the latest survey by the National Council of La Raza.

Immigration is no longer the primary factor driving Latino population growth. In fact, since 2009, the number of Mexican immigrants leaving the U.S., voluntarily and involuntarily, has exceeded the number of new arrivals .

I've been reporting on education for 27 years and covered lots of stories about this population, especially this year as we've set out to report on how the nation can educate the nearly 5 million students who are learning English. And I can't imagine things getting that much worse, especially for Latinos who arrived as toddlers or were born in this country.

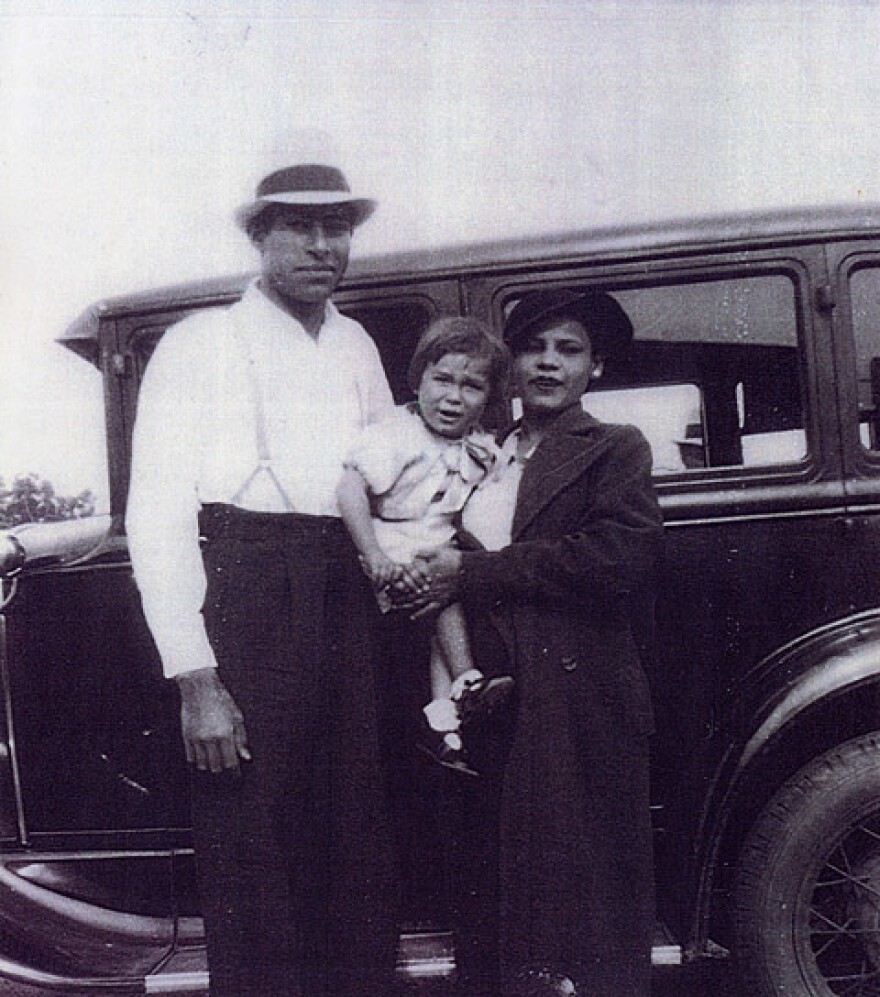

Just look at our history.

Before Brown v. Board of Education, there were schools throughout the southwest that were explicitly created to keep U.S.-born children of Mexican descent separate from white children. As the school superintendent of Garden Grove, Calif., wrote in defense of white-only schools in 1945: "Most children of Mexican descent cannot speak English, have no proper health habits and need training in morals, manners and cleanliness." A school board member in nearby El Modena added, "If we educate the Mexicans better, who would pick our crops?"

Sure, that was a long time ago. Let's fast forward to 1988, the year Lauro Cavazos, a sixth-generation Texan, became the first Latino to serve as Secretary of Education. He drew controversy for berating and blaming Latino immigrant parents for their kids' dismal education. He questioned their values and suggested that education was not a priority for poor Latino families.

From his bully pulpit, Cavazos did little to highlight the awful treatment of these kids at the hands of some uncaring educators and closet segregationists who oversaw education policy at the state and local level. Today, Latinos are among the most segregated students in America.

Then there was President Bill Clinton, who aspired to be the first "education president." For eight years his administration offered little as southern states like his home state of Arkansas struggled to deal with a massive influx of Latino immigrants who took up jobs nobody else would do.

Like the Mexicans in Gainesville, Ga., who were recruited by the poultry industry. I remember how schools in that community were overwhelmed — often they had no Spanish-speaking teachers and as a result Latino students wound up, essentially, warehoused in classrooms with little if any progress toward assimilation — or transition to English.

I remember meeting a gifted, 12-year-old in Pennsylvania, who was classified as "learning disabled" and kept isolated, doing little but memorizing things like the names of kitchen utensils because she didn't know English. She turned out to be a math whiz.

In 2000, George W. Bush came along with his slogan, "the soft bigotry of low expectations," denouncing the education system's penchant for expecting little of these children. He sought to reverse the poor quality of instruction for black and Latino immigrant kids like those his own state — Texas — had long neglected.

Fourteen years of No Child Left Behind followed. While there was some progress on achievement and improving graduation rates, NCLB hardly put a dent on what many would see as the biggest problem: the enormous gaps in resources between affluent schools and those in impoverished neighborhoods.

To this day, little or no meaningful preparation for college or work takes place in many of these "majority-minority" schools. " Persistent disparities" — that's how researchers at the U.S. Education Department today describe the yawning gaps in educational quality and opportunity for Latino and non-English-speaking kids.

Those children are less likely to have access to college-prep classes in math and science. They're less likely to be enrolled in talented and gifted programs and more likely to go to a school where school cops outnumberguidance counselors.

No Child Left Behind? I don't think so, but you have to admit it was a catchy slogan.

The Obama Era

The historic election of the nation's first African-American president was supposed to usher in a new era of opportunity and hope for Americans who've felt disenfranchised. But right before, and after, Barack Obama took office in 2008, immigration and Border Patrol agents were swooping down on communities, raiding companies that illegally hired workers, mostly from Mexico and Latin America.

I was there, in New Bedford, Mass., and Laurel, Miss., a few days after workers were arrested and put into vans and airplanes destined for the U.S.-Mexico border. Many of these people were fathers and mothers, torn from their children, leaving those kids in limbo, sometimes in the care of teachers or social workers.

This was and still is policy, not the task of some special "deportation" force like the one Donald Trump talked about during his campaign. The Obama administration has, in fact, deported more people than any other previous administration, earning him the nickname " deporter-in-chief."

We are, after all, as much a nation of immigrants as we are a nation of laws.

And so, under the Obama administration we've deported tens of thousands of "unaccompanied minors" mostly from Central America, many of them fleeing drug gangs and violence. Yashua Cantillano, 13, and his 11-year-old brother Alinhoel from Honduras were typical. I met them in New Orleans. They fled their home in Tegucigalpa with a change of clothes, water and their mother's phone number in New Orleans scribbled on a piece of paper.

In the short time Yashua was enrolled in a school in eastern New Orleans, he was among the top achieving students in his class. He was happy and finally felt safe. When I called months later to see what happened, Yashua and his entire family had been deported.

The National Council of La Raza this summer released some eye-opening figures. They show that Latinos under 18 years of age now total 18.2 million in the U.S., a 47 percent spike since 2000.

Most, 62 percent, live in poverty. By 2023, they'll make up a third of the nation's total K-12 school enrollment.

So, the question remains. Should Latinos and immigrant kids in particular be more afraid of being profiled and targeted for deportation just because Donald Trump got elected?

Are they more likely to be denied a quality education?

We don't know. What I do know for certain is that life for many of these young people has never been easy, in or out of school. Its been pretty tough for a long, long time.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.