What Einstein did for physics, a Spaniard named Santiago Ramón y Cajal did for neuroscience more than a century ago.

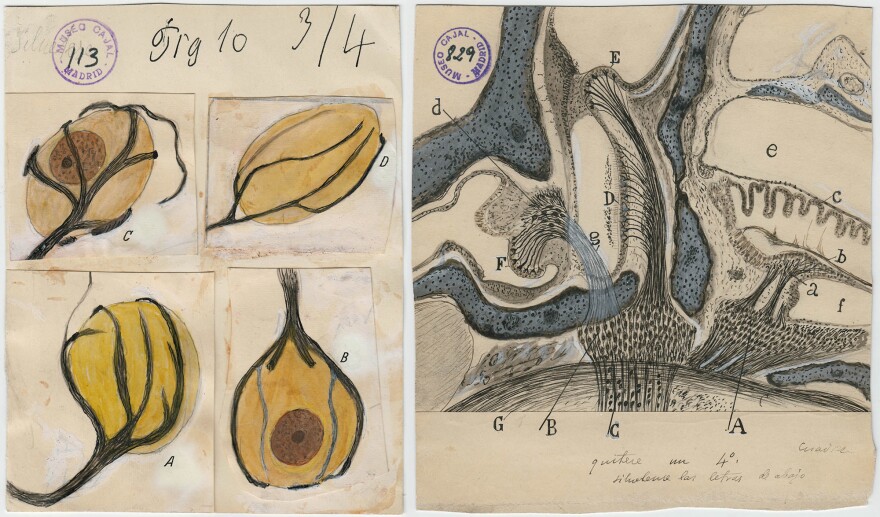

Back in the 1890s, Cajal produced a series of drawings of brain cells that would radically change scientists' understanding of the brain.

And Cajal's drawings aren't just important to science. They are considered so striking that the Weisman Art Museum in Minneapolis has organized a traveling exhibition of Cajal's work called The Beautiful Brain.

"Cahal was the founder of modern neuroscience," says Larry Swanson, a brain scientist at the University of Southern California who wrote an essay for the book that accompanies the exhibit.

"Before Cajal it was just completely different," Swanson says. "Most of the neuroscientists in the mid-19th century thought the nervous system was organized almost like a fishing net."

They saw the brain and nervous system as a single, continuous web, not a collection of separate cells. But Cajal reached a different conclusion.

"Cajal looked under the microscope at different parts of the brain and said, 'It's not like a fishing net,'" Swanson says. "There are individual units called nerve cells or neurons that are put together in chains to form circuits."

Cajal didn't just take notes on what he saw. He made thousands of highly detailed drawings, many of which are considered works of art.

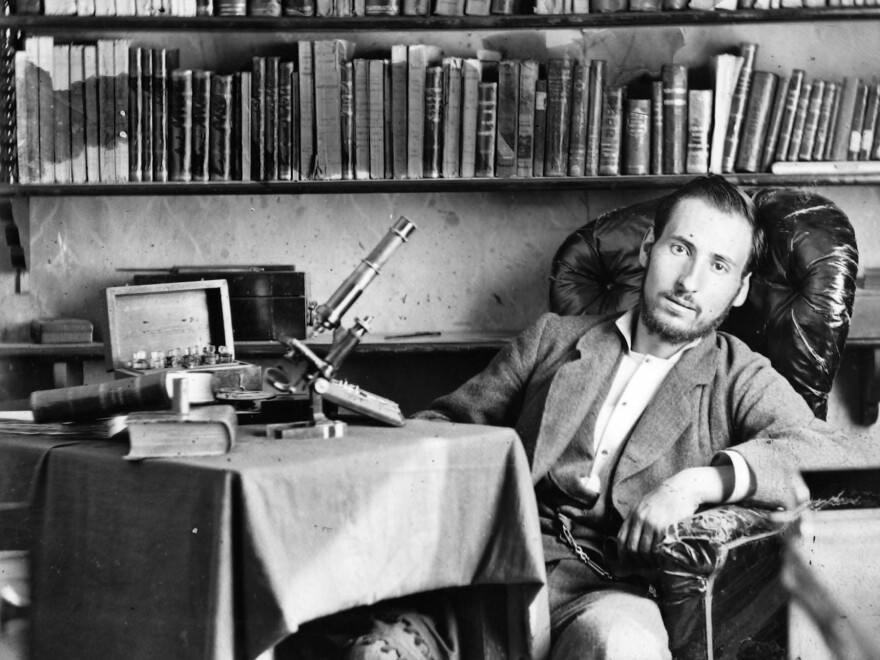

That talent reflected Cajal's early training. As a young man, Cajal planned to be an artist. He sketched compulsively, and even taught himself photography.

But Cajal's father, a doctor, wanted his son to study medicine. So Cajal did. But he also began sketching what he saw during dissections and autopsies, and, later, through the lens of a microscope.

In his 30s, Cajal began to focus on the brain and nervous system. And he used a new cell staining method that revealed not only the cell body, but the delicate projections that allow communication with other cells.

"You see these black outlines," Swanson says. "There are hundreds of different shapes, like trees, like plants."

Cajal shared the Nobel Prize in 1906 with the Italian scientist Camillo Golgi, who devised the new cell-staining method but didn't share Cajal's ideas about the brain.

Decades later, electron microscopes would confirm Cajal's theory. And his drawings are still found in many neuroscience textbooks.

"The model of the nerve cell that everybody still learns is the one that Cajal laid out basically in the 1890s," Swanson says.

Yet today, Cajal is relatively unknown outside of scientific circles.

The name meant nothing to Lyndel King, who directs the Weisman Art Museum, when she was approached by two brain scientists from the University of Minnesota several years ago. The scientists were trying to interest King in organizing an exhibition of Cajal's drawings.

"I looked at some of them in books and I said, 'Wow, yes, we are going to do this,'" King says. "They are beautiful, beautiful drawings. They are scientific drawings, but they are art at the same time."

It took years to arrange the exhibition with the Cajal Institute in Madrid and the Spanish government. And it might never have happened without help from Alfonso Araque, a neuroscientist at the University of Minnesota who had previously worked at the Cajal Institute.

Choosing which drawings to include also proved challenging, King says. Artists and scientists often had different priorities, she says.

"They might say, 'Oh, this drawing is absolutely really important scientifically,' " King says. "And I would say, 'Yeah, but it's really dull visually. It's not aesthetically appealing.' "

Eventually King and the scientists agreed on 80 drawings. And many of them evoke much more than just brain anatomy," King says.

One of her favorites depicts glial cells from the cerebral cortex of a child. "To me it looks like fireworks, the Fourth of July," she says.

Another drawing reveals Cajal's whimsical side. It shows a damaged neuron in the cerebellum that seems to have more than an accidental resemblance to a penguin.

Perhaps the most important message from the Cajal exhibit is that art and science can work together, King says.

"Drawing is a way of thinking," she says. "And Cajal made these drawings as part of his thinking through his theories about the brain."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.