China's President Xi Jinping finished 2017 vowing to boost China's role on the world stage.

"As a responsible major country, China has something to say," Xi said in his Dec. 31 New Year speech. "China will resolutely uphold the authority and status of the United Nations, actively fulfill China's international obligations and duties, remain firmly committed to China's pledges to tackle climate change, actively push for the Belt and Road Initiative, and always be a builder of world peace, contributor of global development and keeper of international order. The Chinese people are ready to chart out a more prosperous, peaceful future for humanity, with people from other countries."

Meanwhile, Chinese diplomats closed out the year with a barrage of summit meetings in Beijing and diplomatic initiatives in the world's hot spots, including Afghanistan and Myanmar.

Analysts in China say the proactive statesmanship is befitting the new era Xi has declared, in which China confidently wields its newly acquired wealth and influence and resumes what it considers its rightful place at the center of global affairs rather than leaving world problems to the United States and other countries to deal with.

With China's economy on track to overtake the U.S.'s in the coming years, "We no longer need to keep a low profile on many issues," says Tsinghua University international relations professor Zhao Kejin, one of several Chinese scholars and think tank experts who have dubbed China's new assertiveness "powerful nation diplomacy."

"We want to plan actively," Zhao says, and not react passively to the U.S. and other nations. "We want to provide more Chinese solutions and Chinese wisdom to the international community... We also want to play a bigger role in the reform of global governance."

The rhetoric of "powerful nation diplomacy" appears to be an effort by Chinese commentators to interpret and amplify Xi's ideas.

At the October congress of the ruling Communist Party, Xi said that the example of China's rise "gives a new choice to nations and peoples who want to develop faster, while maintaining their independence" from foreign domination.

But at a summit of foreign political parties in early December, Xi cautioned, "We will not export the China model" — as Beijing did under Mao Zedong, supporting and arming Communist insurgencies in Southeast Asia during the 1960s and 1970s.

Still, there is debate about the sustainability of China's economic growth and its capacity for global leadership, David Kelly, a director of research at the Beijing-based advisory firm China Policy, observes.

"If you speed up very fast," Kelly says, "you find that you're up against a barrier of other powers bandwagoning against you" — resulting in diplomatic isolation.

China recently won favor in Myanmar, though, for supporting that country's government, led by Aung San Suu Kyi, as it faces accusations of ethnic cleansing against Rohingya Muslims.

The plight of the Rohingya is widely seen as a humanitarian crisis affecting much of Southeast Asia. The inaction of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations appears to have left a dearth of regional leadership and solutions, which China has tried to fill.

While Western governments have threatened sanctions, China has spoken in support of Myanmar's "safeguarding peace and stability." It also offered to broker a solution, including negotiations on the Rohingya, without any mention of allegations of ethnic cleansing or the Rohingya's stateless condition.

The epicenter of the conflict, in Myanmar's far western Rakhine State, also happens to be the site of strategic Chinese investments, including the Kyaukphyu deep-water port and the southwest terminus of an oil and gas pipeline that extends into China.

"So instead of providing a public good, there's also a more narrow self-interest, which may also be a part of the 'powerful nation diplomacy' doctrine," says analyst Joost van Deutekom of China Policy.

China also has substantial investments in Zimbabwe, where Beijing surprised some observers by not coming to the aid of its longtime ally Robert Mugabe, who stepped down as the country's longtime leader in November after the military placed him under house arrest. Zimbabwe's military leader had visited Beijing just days before, in what China said was a "normal military exchange."

"There was a move by Mugabe to nationalize diamond assets, to China's disadvantage," Kelly points out. So again, he notes, China's diplomacy "was not clear of self-interest."

Another old friend of China, Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen, fared better in 2017. When his government jailed a key opposition leader for treason and Cambodia's Supreme Court dissolved the country's main opposition party — in effect creating a one-party state — Western governments criticized the move. But China supported Cambodia's efforts to "protect political stability," the foreign ministry said in November.

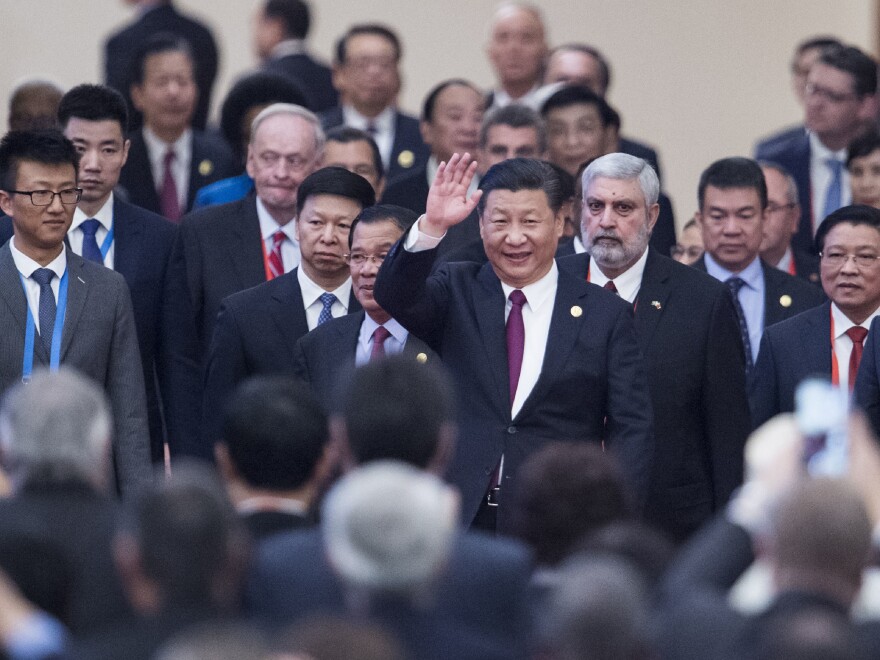

Meanwhile, throughout the final month of 2017, China welcomed foreign heads of state and emissaries attending high-level meetings. Last week, Beijing hosted foreign ministers from Pakistan and Afghanistan for a regional dialogue aimed at improving relations. Earlier in December, heads of state including Suu Kyi and Hun Sen attended a summit of political parties organized by China's Communist Party.

Outside Shanghai, tech moguls attended a " World Internet Summit," which trumpeted China's idea of "Internet sovereignty," meaning that national governments must be able to control Internet content within their own borders. And China held a human rights conference for developing nations, at which it promoted a human rights agenda "with Chinese characteristics."

China considers human rights a sovereign matter in which other nations have no right to interfere or criticize. "No one is in a position to lecture others on human rights," Foreign Minister Wang Yi admonished attendees.

Kelly says until very recently, China portrayed itself as a developing nation and tried to limit expectations of its influence. China "was like a failing football team," he says. "We're going to take the flag one of these years," it seemed to say — but there's no rushing it.

China's reluctance to adopt a higher profile in international affairs has been undercut by its own rapid development and by global developments including the 2008 financial crisis, the Middle East wars, Britain's exit from the European Union and the election of Donald Trump.

But Tsinghua University's Zhao argues that China is not keen to replace the U.S. on the world stage.

"If the U.S. is No. 1, then we're No. 2," he says. "We know that leadership has high costs, and we don't want to bear them. We'd rather the U.S. do that."

Besides, Zhao argues, it's hard for China to aspire to true superpower status when it is not whole and complete, with a rival government ruling the island of Taiwan and an exiled administration in India contesting the leadership of Tibet.

David Kelly also cautions that views of China's "powerful nation diplomacy" are by no means unanimous.

"The sustainability of wealth and power is very much up for debate," he says. Assumptions about China's future economic strength rest on the country's past success in meeting U.S. and European manufacturing needs of the 1990s and 2000s.

In other words, "That growth was based on the world economy at that time," he says, "and it's no longer the same world economy."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.