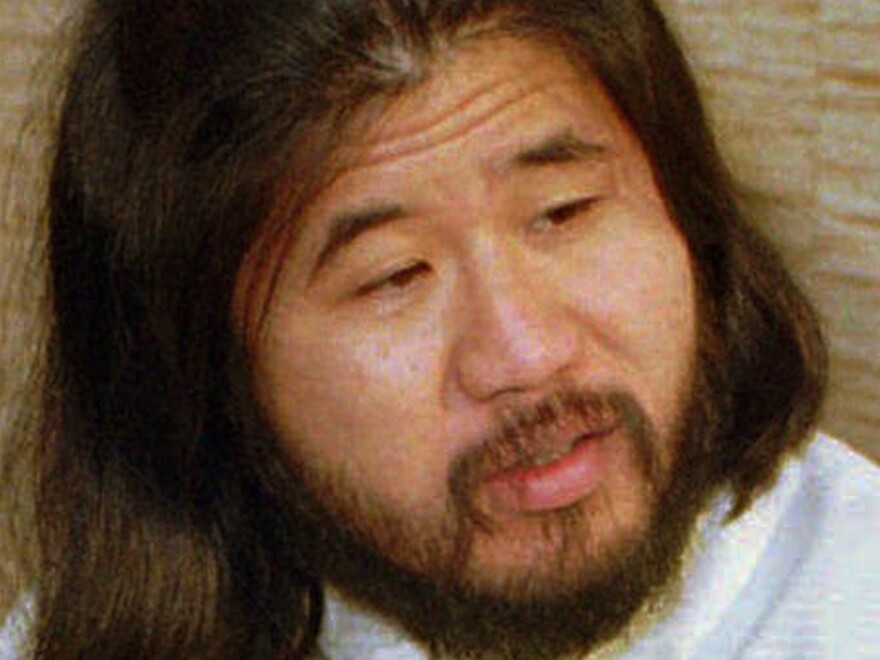

Shoko Asahara, the leader of the Japanese doomsday cult that carried out a deadly 1995 sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway system, was executed by hanging Friday along with six of his followers.

Asahara, the visually impaired self-styled guru of Aum Shinrikyo, was sentenced to death in 2004 in part for directing Japan's deadliest terrorist attack — a complex plot that came to fruition on March 20, 1995, when cult members boarded five trains during morning rush hour and released the nerve agent, killing 13 people and sickening some 6,000 others.

The death of Asahara appeared to draw the curtain on the cult's shocking crimes, which included not only the 1995 subway attack but also a similar, smaller sarin attack the previous year along with other attacks using the deadly chemical VX.

Asahara was convicted of taking part in 13 crimes that led to the deaths of 27 people, which later became 29, according to The Japan Times.

Asahara, born as Chizuo Matsumoto, founded the group that became Aum Shinrikyo, or Supreme Truth, in 1984.

According to the Associated Press, the cult leader "used a mixture of Hinduism, Buddhism, Christianity and yoga to draw followers. They took part in bizarre rituals, such as drinking his bathwater and wearing electrical caps they believed synchronized their brain waves with Asahara's."

Aum Shinrikyo attracted young, well-educated adherents, including scientists who then helped produce the poisons used in the cult's attacks. The group has since splintered and went on under the name Aleph.

Friday's executions provided closure for family members of those killed, such as Kiyoe Iwata, whose daughter died in the subway attack.

"This gave me a peace of mind," Iwata told Japanese broadcaster NHK, according to the AP. "I have always been wondering why it had to be my daughter and why she had to be killed. Now, I can pay a visit to her grave and tell her of this."

In Asahara's eight-year trial, he spoke incoherently and never explained the motive for the attacks or acknowledged responsibility.

As a result, The Japan Times notes that the cult leader's death "leaves several critical questions unanswered, because even during his trial, Asahara never explained the actual motivations for the crimes."

Some family members of the cult's victims are more interested in those answers than they are in retribution.

"I wanted the others to talk more about what they did as lessons for anti-terrorism measures in this country, and I wanted the authorities and experts to learn more from them," Shizue Takahashi, whose husband was a subway deputy station master and died in the attack, reportedly told a news conference.

"I regret that is no longer possible," she said.

Other cult members hanged on Friday included scientists who helped produce the sarin in an Aum laboratory, the cult's "intelligence" director, a member responsible for capturing potential cult defectors and the cult's director for acquiring land.

Six other cult members reportedly remain on death row.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.