Usually Meals on Wheels means home delivery or lunch at a senior center. For more than 50 years, the federal government has been funding the program to make sure older Americans get the nutrition they need. Now, a project in Vancouver, Wash., is trying to use those funds for something new: a retro-hip diner, where seniors can get eggs, coffee, and community.

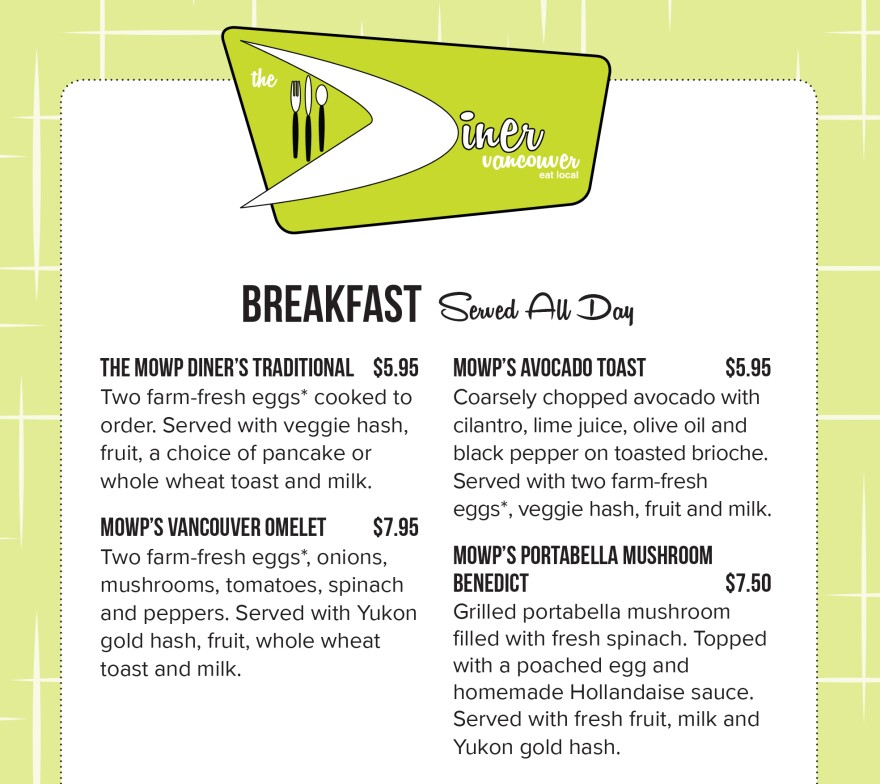

On the surface, The Diner looks like any other diner. Servers making sure the coffee is topped off, local business people having meetings, regulars who know the whole menu. There are the usual diner specialties, with some modern nods — cage-free eggs and local produce — and a retro vibe.

"They play Frank Sinatra in the mornings, and it makes me so happy," says Autumn Zukauskus, who comes for breakfast weekly. "Eggs and Frank Sinatra: perfect breakfast."

But when a younger patron like Zukauskus reaches for her credit card, seniors like Chris Bingenheimer pull out a little green dining card.

"If you can donate, you do. If you don't, you don't," Bingenheimer explains. "And it's no big deal to them."

That's because the entire diner is a project of the local organization Meals on Wheels People. If you look closer, you'll notice a few differences from other restaurants. The chairs are on casters, to scoot out easily if they need to make space for a wheelchair. The coffee cups have large handles, to accommodate arthritic fingers. The building and finishes were designed and selected to minimize noise and maximize comfort.

Avoiding stigma

Suzanne Washington is the CEO of Meals on Wheels People, which serves about 5,000 meals a day. Most of these are home delivery, and about a third are in senior centers. But people don't always want to go to a senior center.

"We heard lots of folks say it was just too much of a stigma to go," Washington says.

Some baby boomers think senior centers are just for their grandparents. Or they're still working, and can't get away for lunch. So, Washington thought, 'Why not try a restaurant?'

"A restaurant that is inter-generational. It's good food," says Washington. "And at the same time, the paying public can help offset the cost of those in our program."

There's a slightly different menu for participating seniors — like an added fruit cup or a glass of milk — to meet nutritional requirements. And some regular menu items aren't part of the program.

"Because we can never make eggs benedict meet regulations," Washington says. "It just doesn't work."

But the menu is still delicious, and the diner's been averaging 140 subsidized meals each month. They've signed up an average of 38 new members per month — about three times the number that sign up for Meals on Wheels at their traditional senior centers. And those who come for the meal donate more for it — the average donation is $2.46, which is four times higher than the donation at a senior center. And for an organization that provides 1.2 million senior meals annually, every increase is significant.

New sign-ups also get a visit from a client service coordinator, who does assessments, and checks if seniors need to be connected to additional services — the sort of information that they might have found at a traditional senior center.

The decline in participation at traditional senior centers isn't just a problem in the Pacific Northwest.

"It is a national trend, where many senior centers are witnessing declining participation rates," explains Manoj Pardasani, a provost and professor of social work at Hunter College.

Providing engagement

Pardasani says the decline is due to a number of factors: centers that haven't innovated to reflect the diversity of the population, or people who look down on senior centers as something only for "needy" people. And he says the downturn is concerning, because these centers provide far more than just food. They provide community engagement, and combat isolation, which provides a benefit for mental and emotional health.

"The core belief behind meals is the socialization aspect," says Pardasani. "We're human beings, we've been socialized to be social animals."

And The Diner is a social place. You can see it in the customers joking with the staff, the people who bring in an older neighbors, the seniors who carpool together for a meal.

Young people like Amber Zukauskus come for that camaraderie just as much as for the little pies.

"Everyone here is so nice," says Zukauskus. "And they pay everybody a living wage, and so all your tips just go to donations for Meals on Wheels, which is amazing. That's something I want to give money to."

The Diner has gone through the usual hiccups of starting a new restaurant — dealing with staffing, figuring out the lunch rush, adjusting portion size so that seniors might have some extra to take home and eat later. Meals on Wheels People received some grant money to help with start up costs, and they expect to turn a profit in their third year. But even early on, they seem to be hitting their stride. It's a bustling, thriving business.

Chris Bingenheimer learned about The Diner from a friend, and came in to share a meal. He sometimes goes to a senior center, but was never a fan of the made-in-advance food, or the minimal choices, or of the fact he had to be called up for a meal like at the high school cafeteria. He said he'll definitely be back to The Diner.

"The staff is very friendly," says Bingenheimer. "They don't look down on you because you're with the Meals on Wheels program. They treat you kindly. The service is impeccable."

Bingenheimer is a senior using Meals on Wheels. And at The Diner, he's also just a guy, sitting with a friend, having a good breakfast.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.