The Vietnam War divided the country – and families – including that of Kansas City writer Alan Robert Proctor. His brother, Bruce Proctor, worked in the Pentagon’s Defense Intelligence Agency before fleeing the country to avoid being sent to Vietnam.

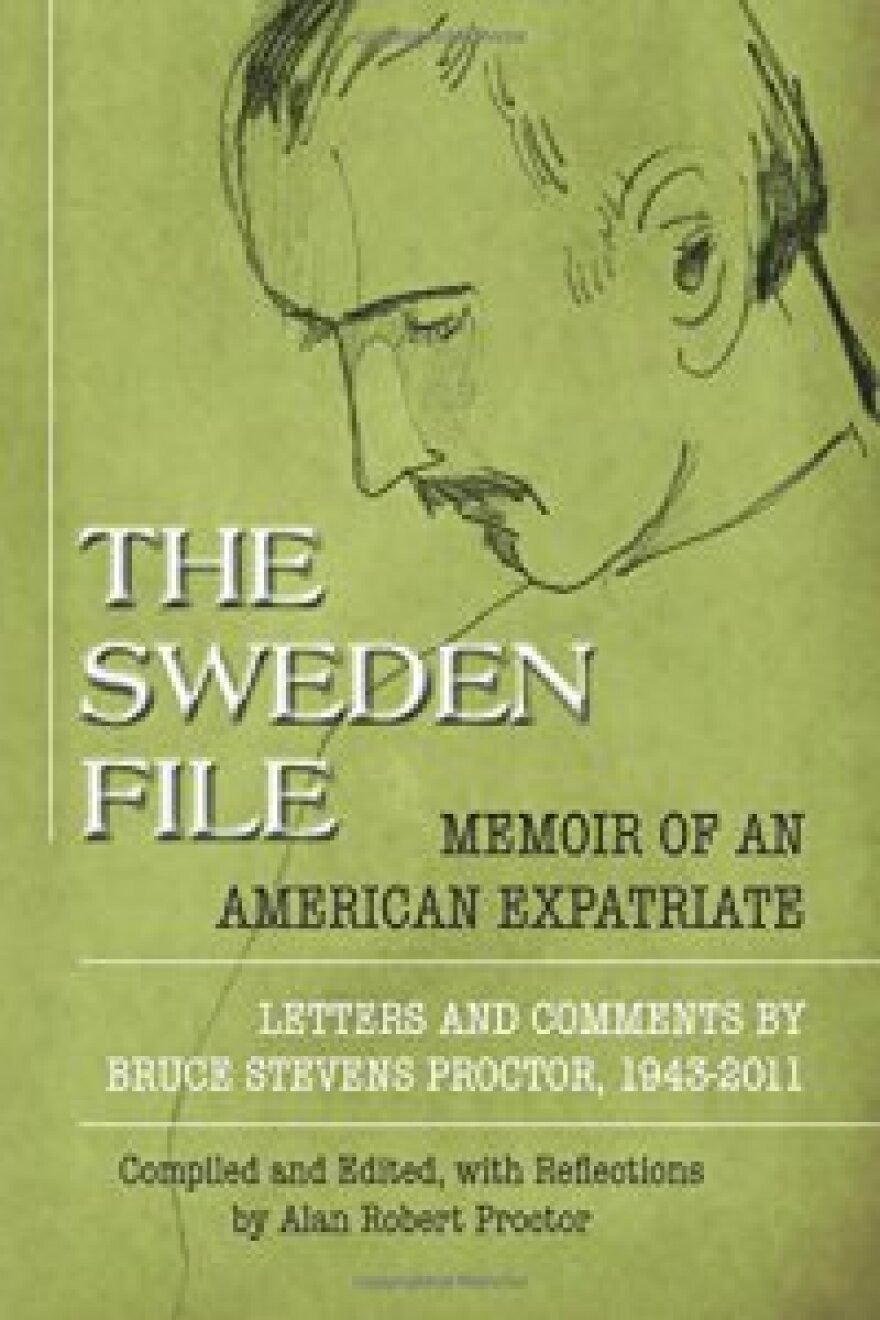

Bruce Proctor lived in Stockholm, Sweden, from 1968 to 1972 before moving to Canada, where he died in 2011. Last year, Proctor published The Sweden File: Memoir of an American Expatriate. It includes his brother’s letters home, with commentary by both men looking back on those days.

JANOVY: You went back and found the letters in a file cabinet and decided you were going to compile them into a manuscript. You sent that to him and asked him to “reminisce on his youthful correspondence,” which he did — you say he “took your suggestion to heart and recounted a more complete panorama of his banishment.”

PROCTOR: His story and his journey is rather harrowing. In 1967, he was interpreting aerial photography taken over Vietnam and what he saw horrified him. There were dead civilians, bomb craters on unauthorized flight paths. And he decided he couldn’t work for a government that was involved in this kind of war, so he told the DIA I’m quitting. And the DIA said you can’t quit, you have to be debriefed, and that will take six months. My brother said no, I’m leaving tomorrow.

So there he was a civilian on the street with top secret information. He was counseled by friends to join the air national guard because the air national guards at that time were not going into foreign combat. But within a few months, President Johnson nationalized his unit and several others with orders to go to Vietnam. So he went AWOL, and flew to Stockholm, Sweden. His first letters were highly optimistic, but as it turned out life was not at all easy for him.

JANOVY: In some of the letters he’s ambitious and he’s talking about school, or he’s enrolled in school. And then there are other letters where he’s really not even coherent.

PROCTOR: Right.

JANOVY: Are there two or three that really stand out to you?

PROCTOR: Bruce could be enigmatic, philosophical, funny — all in one paragraph. Maybe what I should do is read his first letter. It’s "Chapter 1, AWOL, Saturday, July 13, 1968 (posted in New York City)."

Dear Folks,

There was reason, after all, for resignation to my fate. If I had really planned to go I would have been very morbid. I have no desire to assist in the death of people. The war in Vietnam is irrational, immoral and stupid. I'm on the bus to New York where I'll fly to Stockholm, Sweden tonight. Rosemary (Bruce's wife) will follow in 3-4 weeks after liquidating our modest property. I'll write as soon as I have an address in Stockholm. We know people there, so I'll be staying with friends. My first problem will be the language but the government has free courses. There will be no problem with working; the Swedish law is very liberal with political refugees; they enjoy a sanctuary. Naturally I do not plan to return unless there is, eventually, a legal way to do it. The Swedes run a rational social order so there will be no problem with ordinary amenities of health and living. My strength and certainty that this is the right decision grows; I can feel that it is right. I do not seek an escape or transformation, I'm merely changing my territorial basis...

Well, terribly, terribly optimistic. And let me read you now, his reminiscence of that first day when he was waiting for his plane to go to Sweden at LaGuardia National Airport. I should say he mentions the village of East Hampton, New York. Our family summered there while we were growing up. My father had a small cottage there on the harbor, Three Mile Harbor. So he’s in the airport.

The wait seemed interminable, but I eventually boarded and found my window seat on the left side of the big jet. Taking off over Long Island, heading East, I gazed down at the Atlantic beaches of Long Island. Soon, however, clouds obscured the view and I was not able to spot the South Fork, East Hampton, or Three Mile Harbor. I cried. It came over me suddenly, no tears at first, just a shuddering in my chest and an effort to breathe normally. Never again to play in the surf, sit in the dunes, share lunch on the beach, go skin-diving and fishing in the harbor. Never again to take out the kayak, paddle in the early morning fog. All these memories washed through me in long sobs. And, just to compound all that, thoughts of others followed in quick succession: the loss and unknown reaction of my mother, father, brothers, and sister.

So, that's what was really going on.

JANOVY: The emotions that he evokes are so universal for anyone who’s left home. He’s thinking that he’s never coming back and you’re thinking of him leaving and never seeing him again. Is that what you’re feeling as you’re reading?

PROCTOR: Yes. Yes, because he never did, except to visit, luckily, for a lot of us I guess, President Carter on his second day in office reviewed a lot of the dishonorable discharges for humanitarian reasons he upgraded many of them to less than honorable discharges and my brother’s was one of them. So he was able to come back and at least visit.

JANOVY: He knew this manuscript existed, and there would be this document of his life and his experience. That had to be gratifying for him?

PROCTOR: I hope so. One of my deep regrets is that he was not alive when it was published. I guess he didn’t know I was going to add my own commentary and put it into chapters and edit it and get David Ray to write the preface, but I’m very sorry he isn’t around to see this.

C.J. Janovy is an arts reporter for KCUR 89.3. You can find her on Twitter, @cjjanovy.