People don't often think about preserving the valuable things they own on paper until it's too late. But when that time comes, one Kansas City man is often able to help.

Mark Stevenson is used to seeing paper in every state of disrepair. A professional paper conservator, he has spent the past 25 years restoring prints for prestigious museums both large, such as the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. and The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, and and small like The Fogg Art Museum at Harvard.

Stevenson also works for individual clients. He's often astonished by the things that people bring him. One family brought him a Revolutionary War officer's commission from September 1777.

“Part of what I love about what I do is, it's kind of a rotating museum,” Stevenson says. “I get to live with these things and interact on a very intimate level."

Each piece of paper is a puzzle. Sometimes it's difficult to know what path to take in a restoration.

“It's all very delicate,” Stevenson says. “You do sort of have to balance a feather on your nose some days."

It can also be physically exhausting. He can spend hours hunched over a worktable in his Midtown home, intensely focused on fragile documents.

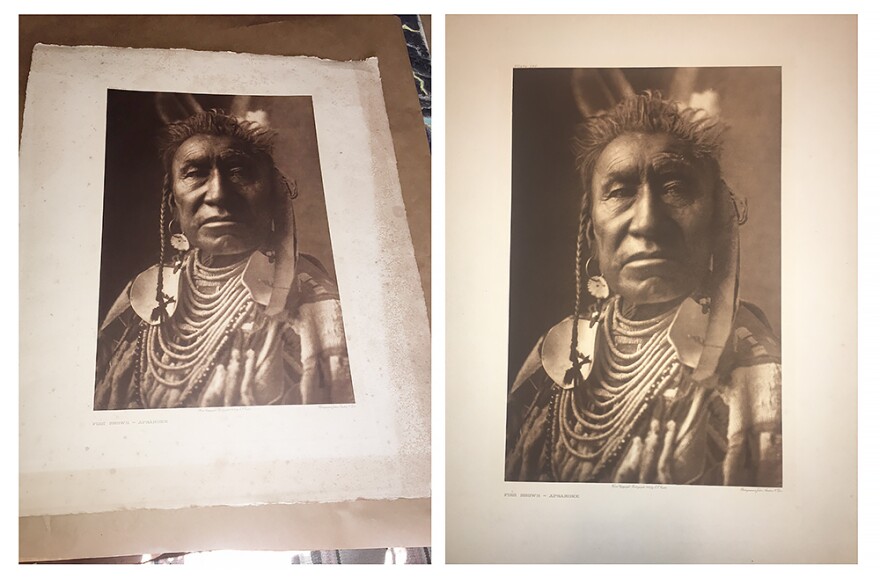

One recent customer was Matt Denney, an amateur art collector who from Parkville who brought Stevenson a recent acquisition from an auction: a photogravure of an Apsaroke (or Crow) warrior, one of thousands of images made more than a century ago by Edward Curtis, a famous American photographer who spent two decades photographing Native Americans in the West.

“When I purchased it, it was hanging from a clothesline,” Denney said. “There was a lot of staining around the perimeter of the print and it just looked terrible."

It took Stevenson six weeks, but when he was finished with Denney's piece, the paper was bright and clean. Stevenson has removed the stains of age to show the weathered face of a man who sat for Curtis more than a century ago.

“Wow! Oh my goodness,” Denney said when he saw it. “That is breathtaking. You’re a magician, man. This is pretty incredible.”

Burton Dunbar, a retired professor of art history at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, often works on projects with Stevenson.

“Works on paper are incredibly fragile,” he says. “They don't like light. They don't like dampness. They like to be put away for long periods of time. That's why museums will exhibit a work on paper for a period of time and then put it to bed for maybe five years."

But he says the beauty of works on paper makes the effort worthwhile.

“With works on paper, you find yourself taking a breath,” Dunbar says. “How lush they are even though they may be black and white, the extremes in value that we have from pure white to deepest black.”

Dunbar says that's where people like Mark Stevenson come in. All of the objects Stevenson repairs are valuable. Sometimes that value is monetary, sometimes it's sentimental.

Another recent client wanted him to stabilize old family letters.

“Human beings, being the strange creatures that they are, we invest inanimate objects with meaning and we form emotional bonds to them whether it's your mink coat, your new car or your family documents," Stevenson notes.

Nursing cherished works on paper back to health is a big responsibility, and Stevenson says in many ways the most rewarding part of what he does is helping out. Sometimes that involves walking people through their grief.

“Whether it was the basement flooded or something fell off the wall and the glass cracked and tore something, they bring them to you and you can tell these people are just distraught,” he says. “And it's like, 'OK, let me see what I can do.' And quite often something can be done."

There are limitations and even risks to repairing damage. Occasionally an object is beyond saving, and he finds himself helping people come to terms with loss.

“Two of my great grandfathers were ministers. My grandfather was a pharmacist. My father was a pharmacist. I come from a long line of healers," Stevenson says.

He says he's come to see his job as "a healing thing" as well.

"It’s a cultural healing, sometimes it's a personal healing."

Julie Denesha is a freelance photographer and reporter for KCUR. Follow her on Twitter, @juliedenesha.