As a teenager in Queens, New York, Vladimir Sainte often didn't want to go home after school. So he didn't. His parents, Haitian immigrants, worked several jobs, and Sainte had become a defiant and anxious boy.

When his parents decided they could no longer manage him, they shipped him to Kansas City to live with his uncle. He was 16 then. But now, years later in his career as a social worker, he sees he could have been taught to manage his emotions better.

Children, he notes, don't have the "verbal literacy" of adults.

"Their brains are not fully developed. It's our job — slash — our mandate as adults to teach them those emotional skills for self-regulation, for communication," he says.

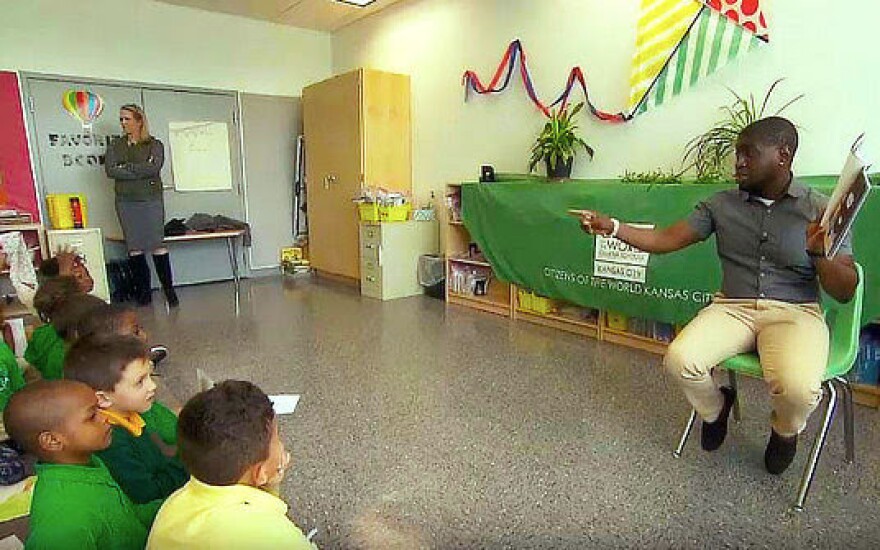

One way he teaches kids the ideas of self-worth and self-soothing is bibliotherapy — reading books that show a character dealing with similar issues.

During sessions with one particular African American boy, however, no book seemed to fit the situation. That was largely because there aren't many children of color depicted in books that deal with mental health. Like Sainte as a child, the boy literally was not comfortable in his own skin.

"I remember just feeling that way, and what really hit home for me was working with this kiddo who was not okay with his skin tone to the point where he wanted to take sandpaper, and he thought he could rub it off," Sainte says.

He decided to write and illustrate a series of children's books.

"I love art, I know mental health," he recalls thinking. "If I want to see this, then I need to be the change and do it myself."

The first book, "Just Like a Hero," is about an African American boy who powers his way to good self-esteem.

The second in the series, recently released, is called "It Will be Okay." It's about Alma, a Latina girl who learns to combat fear and anxiety.

For that one, Sainte created an antagonist, a fear monster named Mr. Limbo, who watches Alma on monitors as she huddles in a corner and as she texts that no one likes her.

As in "Just Like a Hero," the child character learns tools to care for herself. She creates a "hope shield" with the help of therapist named Mr. Dave.

The shield, Sainte writes, is the "source of her powers on learning ways to conquer her fears. The shield helped remind her of all the things she had learned in therapy."

Things like breathing deeply, taking breaks when needed, and how to tell bullies she's not scared.

Thanks to the shield, Alma is even able to help her friends feel more positive about themselves.

Sainte is a married father of two, and at home he tries to speak openly about how he feels and what he'll do with those emotions. But he recognizes not every parent knows to try that.

"If I was a dad and I didn’t have this clinical background, how can I understand this, digest it, and regurgitate it back to my child?" Sainte says. "I wanted to make the writing simplistic and easy and transferable, so anyone can read it."

He hopes his books will raise awareness about kids who behave the way he once did.

"Just remember that there's more going on to a child than what we're seeing on the outside," he says.

"So if we can take the time to be compassionate and understanding, it will go a long way to helping the individual."

Vladimir Sainte spoke with KCUR on a recent edition of Central Standard. Listen to the full episode here.

Follow KCUR contributor Anne Kniggendorf on Twitter, @AnneKniggendorf.