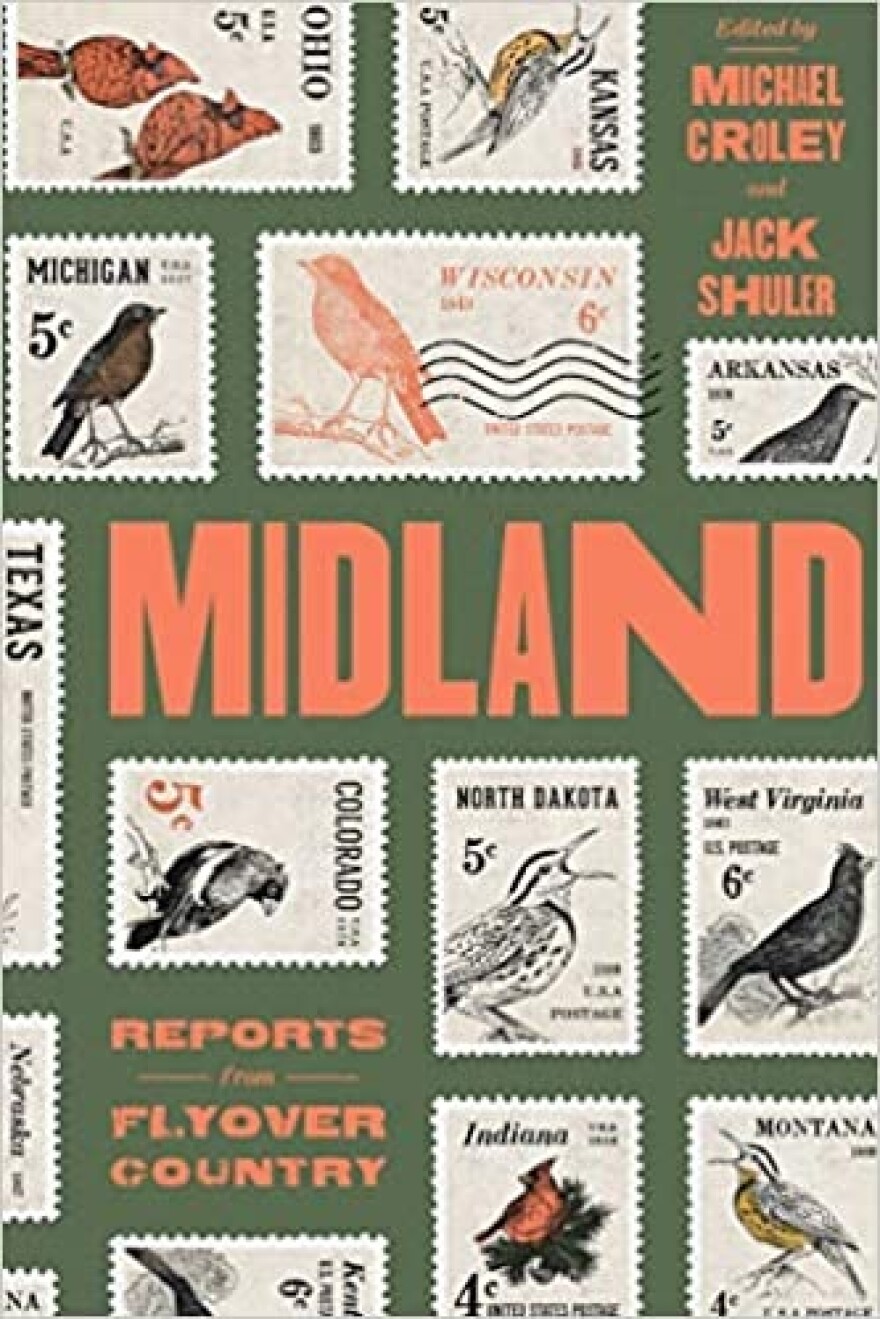

A new book of essays, Midland: Reports from Flyover Country, challenges mainstream media coverage of noncoastal cities. As co-editor Michael Croley puts it, the book is about pushing “out to the coasts, rather than a journalism that pushes in and dictates to the middle of the country.”

Croley is a professor at Denison University in Ohio, where he and other journalists gather a couple times a year for a forum called Between Coasts.

He says the book came out of the forum, which is intended to connect journalists in the middle of the nation with editors from coastal media outlets, so those outlets will be less reliant on “parachute journalism,” in which journalists drop in on a scene, report, and leave.

“When you live in a place, you have a more nuanced understanding of what goes on there, and you don’t just talk to the loudest folks in the diner....and then file your story,” co-editor Jack Shuler says.

When that’s not the case, Croley says, the trouble is two-fold.

Parachute journalism doesn’t allow the journalist enough time to get to know the place or the issues involved, so the coverage becomes what Croley calls an “easy picture,” one which often stereotypes people for quick portraiture.

The result is what the collection’s introduction refers to as “a collage of snapshots rather than a mirror that reflects the complex alignments and vulnerabilities unique to each state.”

Another issue is that residents of stereotyped areas—such residents run into the millions because those areas comprise the majority of the country—no longer trust journalists after they see inaccurate coverage of what they’re most familiar with.

“That’s going to be harder for them to buy breaking news about what the president has lied about or why Congress is stalling on aid for the Coronavirus. There’s a trickle down effect,” Croley says.

Croley and Shuler brought together 23 writers—among them, former KCUR reporters C.J. Janovy and Esther Honig—to showcase the specifics that mainstream media might miss.

Janovy’s essay is called “The Coolest Parents in Johnson County, Kansas,” and is about parents who throw the county’s first LGBTQ picnic as a supportive measure for their child who’d recently come out.

Honig’s essay is set in rural Colorado and deals with the challenges small communities of undocumented workers face, particularly in light of increased immigration raids.

But all of the essays, Croley says, in some way address the idea of community—either the lack or the benefits thereof.

“We’re trying to find common ground. These [writers] are deeply committed to this idea of community,” Croley says.

In some cases, that common ground is within a single family. “Why Can’t We All Just Get Along: A Road Trip with my Trump-Loving Cousin” by Bryan Mealer is about just that. Mealer works toward getting to know a cousin 50 years his senior whom he’d only recently met.

She’s in her 90s and a staunch Trump supporter. He is neither. They road trip to Washington, D.C., together from the Southwest in the hope of meeting the president, but all along the way they meet not only those who side with his cousin, but the very constituents most alienated by the president’s politics.

The idea is that “exposure is the antiseptic to bigotry,” Mealer writes. The result is quite a bit of hugging—the adventure was pre-pandemic—but without a slide into too much sentimentalism.

“We’re not changing the world here,” Mealer writes of the encounters his cousin deems positive. “But the next time Sean Hannity or Laura Ingraham disparages one of her new friends, I hope she’ll remember the baklava.”

Croley hopes the collection will be successful enough to pave the way for similar books. He envisions future collections written by smaller-town journalists addressing income inequality, climate, and race.