There’s something pretty obvious about how the Missouri River divides Kansas City: All the tall buildings are on one side of the river. It seems downtown Kansas City is firmly entrenched on the south side of the river. But … why?

Like so many things in this part of the country, the answer has its roots in the 1800s and how settlers decided things would be.

It might be fun to think that Lewis and Clark had something to do with it. But when the explorers arrived at the intersection of the Kansas and Missouri rivers in 1804, they didn’t write much about the location, except that it was a good place for a trading post, according to Sherry Lamb Shirmer’s book, At River’s Bend: an illustrated history of Kansas City, Independence and Jackson County.

They did extol the virtues of another location to the east, which is where the U.S. Army built Fort Osage to trade with the Osage in Jackson County.

James Shortridge, author of Kansas City and How It Grew, 1822-2011 writes that for a while, Fort Osage had a monopoly on the fur trade, but in 1822, St. Louis business people wanted to get in on the action. They sent Francois and Berenice Chouteau to set up shop in today’s West Bottoms, then called the French Bottoms.

And here we have the first indication of how Kansas City would develop: Both Fort Osage and the Chouteaus’ business were on the south bank of the river along with their trade partners, the Osage, who lived in semi-permanent villages.

On the north side of the river, the Missouria tribe passed through as they followed buffalo. We can only imagine how hard it would be to rely on a roving trading partner.

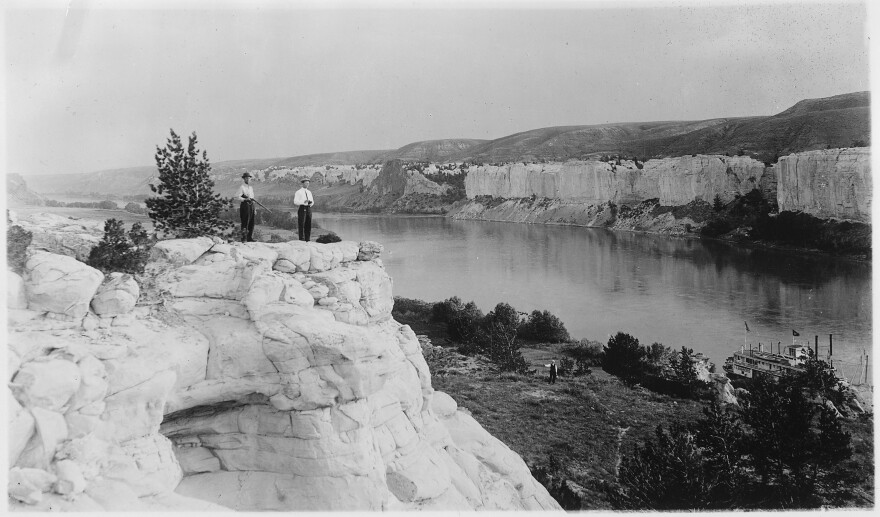

Then there was the matter of the river and the boats that needed to travel on the river. It turns out the south bank was the best place for steamboat landings, according to John Herron, an historian at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

“Pre-Corps of Engineers, the river used to meander around (a lot)," Herron says. "The topography south of the river was always more stable and more elevated and as a result, somewhat protected from a fickle river.”

There’s more, of course. Like the Santa Fe Trail, which took off around the 1840s. That historic trail ran south of the Missouri River, as does Independence, Missouri. Independence flourished because travelers heading west to California and Oregon on the Santa Fe stocked up on goods there.

About this same time there also was a huge Indian migration. The Delaware, Wyandotte and Shawnee tribes were relocated from the Great Lakes region to the Kansas Territory. Westport merchants traded with these immigrant tribes.

So Independence and Westport were established as economic centers, and thus the momentum for development remained south of the river, according to Shortridge. The river was a barrier to the north. Even when crossing the river was possible thanks to early bridges, its floodplain and lack of grassland (for cowherds), got in the way of its development.

So during the industrial revolution, Kansas City, Missouri, and Kansas City, Kansas, saw rapid development and industrialization, but north of the river was just a few small towns — like the town of Harlem — until the turn of the 20th century.

“People in Kansas City’s third close neighbor, Harlem, had only modest aspirations,” says Shortridge. “Harlem at its peak contained a hotel, several saloons, a grocery, a school and a post office.”

And when the slaughterhouses and railroads built up in Kansas City, the large swath of land in the Clay County Bottoms was ignored, Shortridge says.

Willard Winner, who had made a fortune revitalizing Independence, bought the Clay County Bottoms, but an economic crash in the 1890s left him bankrupt before he could build. The Armour and Swift packing companies partnered with the Burlington Railroad and bought Winner’s land. Together they developed the area into a major packing plant, rail yard and the nation’s first planned industrial community – North Kansas City.

And those tall buildings of the 20th century? They rose where the urban action was, south of the river.

This look at the Missouri River is part of KCUR's months-long examination of how geographic borders affect our daily lives in Kansas City. KCUR will go Beyond Our Borders and spark a community conversation through social outreach and innovative journalism.

We will share the history of these lines, how the borders affect the current Kansas City experience and what’s being done to bridge or dissolve them.