Stars are disappearing above the middle of the country.

The night is getting brighter, as light pollution — much of which could be fixed by switching to better bulbs and light fixtures — washes out the views above small and large cities alike.

The college town of Kirksville, Missouri, population 18,000, is nicknamed “the North Star of Missouri,” but spotting that celestial body within city limits is getting harder and harder.

And skyglow in large metros like Kansas City, St. Louis, Minneapolis, San Antonio, Houston, Dallas and Chicago is a key reason those cities now rank among the top 10 riskiest for birds trying to survive spring migration each year.

As skies above the U.S. get about 10% brighter per year, confused birds aren’t the only casualties. Pollinators and other wildlife suffer. Our sleep and wellbeing do, as well.

But astronomer Connie Walker has good news.

Losing night skies isn’t a foregone conclusion, said the scientist at NOIRLab, the U.S.’ national center for ground-based astronomy, based in Tucson, Arizona. Communities could do a lot to protect their starry views both for the sake of the environment and for the breathtaking sight.

“We have a responsibility to maintain that access to a beautiful, dark, starry night sky,” Walker said. “It’s an easy thing to rectify.”

One way to help is to look up at the constellation Orion in February or March and report what you see on a smartphone to Globe At Night, a citizen science project that celebrates its 20th anniversary this month.

This simple act helps scientists track where skyglow is worsening and how fast the change is happening. The stars you can — and can’t — see in and around Orion reveal the extent of light pollution where you live.

Walker, who helped create Globe At Night two decades ago, explains how to participate on the Midwest and Great Plains environmental podcast Up From Dust.

She welcomes as many reports as possible, and especially encourages people to start participating in areas where the program doesn’t often receive data.

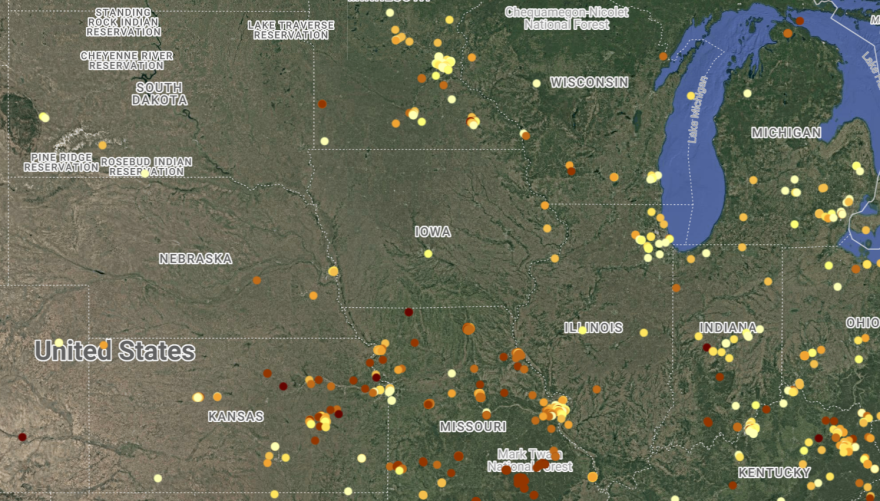

The project’s online interactive map shows that this includes many rural areas — such as much of Nebraska, Iowa, the Dakotas and Kansas.

“A lot more measurements from there would be to everybody’s benefit,” Walker said.

Documenting skyglow is just one step toward addressing it. Some cities, parks and college campuses are working to reduce their skyglow without sacrificing the need for people to see at night. They’re doing this by installing smarter fixtures and better bulbs.

Up From Dust offers three podcast episodes that will get listeners up to speed on the solutions and the stakes.

Episode 1: Say no to skyglow

This episode explains the basics on skyglow and how to reduce it with the right lighting.

It also tells the story of how a Missouri college campus and a state park are ditching bad lighting and installing smarter options.

Park workers, students and faculty are putting to rest any notion that more light is always better. Truman State University students observed just the opposite when they set about improving the lights on their campus. They found that well-designed lighting can reduce skyglow and look softer from afar while actually illuminating spaces better.

“Overall they look dimmer,” Truman State graduate Daphne Broski-Laing said of the improved lights she helped get installed on her campus. “But we measured the brightness underneath the lights and we found that on the ground the illumination level was brighter.”

Truman State professor Vayujeet Gokhale also offers a quick primer for homeowners on picking out good light bulbs and fixtures at a hardware store.

“You can fix the problem in your community if you get together and say, ‘Yes, we need lighting. Let’s do it responsibly,’” he said. “So that we are safe — and yet we can see the stars and yet the pollinators can benefit.”

Episode 2: Can we save millions of migrating birds?

This episode tells the story of one exceptionally determined museum employee, a whopping 40,000 dead birds and a discovery that could save millions from suffering the same fate.

It’s a decades-long journey that started in 1978 and ended up documenting the link between a Chicago convention center’s lighting and the number of birds that crash into it and die.

The center of the country is a vital bird migration corridor, which makes light pollution in cities from Texas to Missouri to Minnesota a particularly dangerous problem for these creatures.

But the discovery in Chicago is helping to inspire families and businesses to turn out unnecessary lights during migration season, pull curtains closed and take other steps to help birds make their long biannual treks.

This episode offers a primer for helping during bird migration season, whether or not you live in one of the major cities that pose the biggest risks.

“The notion that the problem is just in cities is wrong,” Andrew Farnsworth, with the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, explains on the podcast. “Your kitchen window, your living room window, your glass door — whatever it is. When you walk outside and you find a dead bird beneath glass, you can address that.”

Episode 3: Stargazers, unite for science!

This episode explains step-by-step how to participate in Globe At Night.

“It’s a way you can be a steward of your earth,” Walker said, “by looking up and taking these measurements.”

The project has so far gathered 300,000 observations worldwide. In 2023, scientists used this data to conclude that the night sky is getting about 10% brighter per year.

Joining in the effort doesn’t require any special astronomy equipment, Walker said. People simply look at a constellation, such as Orion, and then compare it to several star charts on Globe At Night, selecting the one that best matches what they see.

Participants should do this activity when there’s no moon in the sky, since the moon interferes with accurate measurements. Also, people should make their observations at least 1.5 hours after sunset and at least 1.5 hours before sunrise, to avoid interference from the lingering light of dusk and dawn.

Celia Llopis-Jepsen is an environment reporter for Harvest Public Media and host of the environmental podcast Up From Dust. You can follow her on Bluesky or email her at celia (at) kcur (dot) org.

Harvest Public Media is a collaboration of public media newsrooms in the Midwest and Great Plains. It reports on food systems, agriculture and rural issues.