One day last month, Osawatomie State Hospital had 254 patients in its care — almost 50 more than its optimal capacity.

The overcrowded conditions forced a few dozen patients, all of them coping with a serious mental illness and likely a danger to themselves or others, to be triple-bunked in rooms meant for two.

“It got really crowded there,” says Mark Hornsby, a 56-year-old Topeka man who was an Osawatomie patient earlier this summer. “In the lunch room, you were like elbow-to-elbow. And it got really loud there. It got to a point where I just wanted to stay in my room and not get in trouble.”

With the patient count so high, many of the hospital’s direct-care staff were pressed into working one, two and sometimes three overtime shifts a week.

“The place is over census and understaffed,” says Rebecca Proctor, executive director at the Kansas Organization of State Employees, a labor union that represents many state hospital front-line workers. “Conditions there are really, really bad.”

Angela de Rocha, a spokesperson for Kansas Department for Aging and Disability Services (KDADS), confirms that the Osawatomie hospital’s patient count on July 15 was “an overall high for the past 10 years.”

This isn’t supposed to be happening. In January, Gov. Sam Brownback unveiled his administration's plan to convert the state’s Rainbow Mental Health Facility in Kansas City, Kan., once a 50-bed inpatient hospital, to a privatized crisis stabilization center. The center would connect people with serious and persistent mental illnesses to community-based services, which are less expensive than state hospital care.

The reconfigured facility, now called Rainbow Services Inc., opened April 7. Three and a half months later, admissions at the Osawatomie hospital hit a 10-year high.

De Rocha says the two events — Rainbow’s configuration and the spike in admissions at Osawatomie — were unrelated.

Rainbow, she says, has been successful in keeping would-be patients from Johnson and Wyandotte counties in their communities. The increase, she says, was fueled by “fairly high increases in admissions” for other mental health centers in the eastern third of the state.

A ‘win-win’

That’s not supposed to be happening either. In 1990, Kansas lawmakers passed the Mental Health Reform Act agreeing to adequately fund the state’s community mental health centers in exchange for their help in diverting would-be patients — children and adults — from state-run hospitals in Kansas City, Osawatomie, Larned and Topeka.

The new arrangement, lawmakers agreed, would be a win-win: Better, more humane treatment for the mentally ill and lower overall costs for the state.

The shift from institutionalization to community care was made possible by a federal initiative passed more than 25 years before the Kansas reform law. Shortly before his death in 1963, President John Kennedy signed a bill creating a federal grant program to fund the construction of community mental health centers across the country.

The proliferation of community mental health centers in Kansas allowed the closure of the Topeka State Hospital in 1997, retiring almost 300 inpatient beds from the state-run system. That left the state with hospitals for the mentally ill at Osawatomie and Larned. Combined they are now licensed to care for 282 patients.

For a while, the state’s reform plan worked. But today, directors at many of the 26 community mental health centers in Kansas say the system is breaking down because state funding hasn’t kept pace with the increasing demands for care in their communities.

“The argument can be made, I think, that funding for the CMHCs has either stayed steady or slightly increased from the mid-1990s until about five or six years ago,” says Greg Hennen, executive director at Four County Mental Health Center in Independence. “That’s when — because of the economic strain that was going on at the time — a lot of human-service kinds of things sort of got moved to the back burner.”

Five years ago, he says, Four County had about 3,300 active patients at any given time; today, it has 4,200 and expects to reach the 5,000-patient mark within a year.

Growing numbers of uninsured

One of the biggest problems for the centers is the growing number of uninsured Kansans needing treatment. Statewide, more than half of the patients at community mental health centers are uninsured.

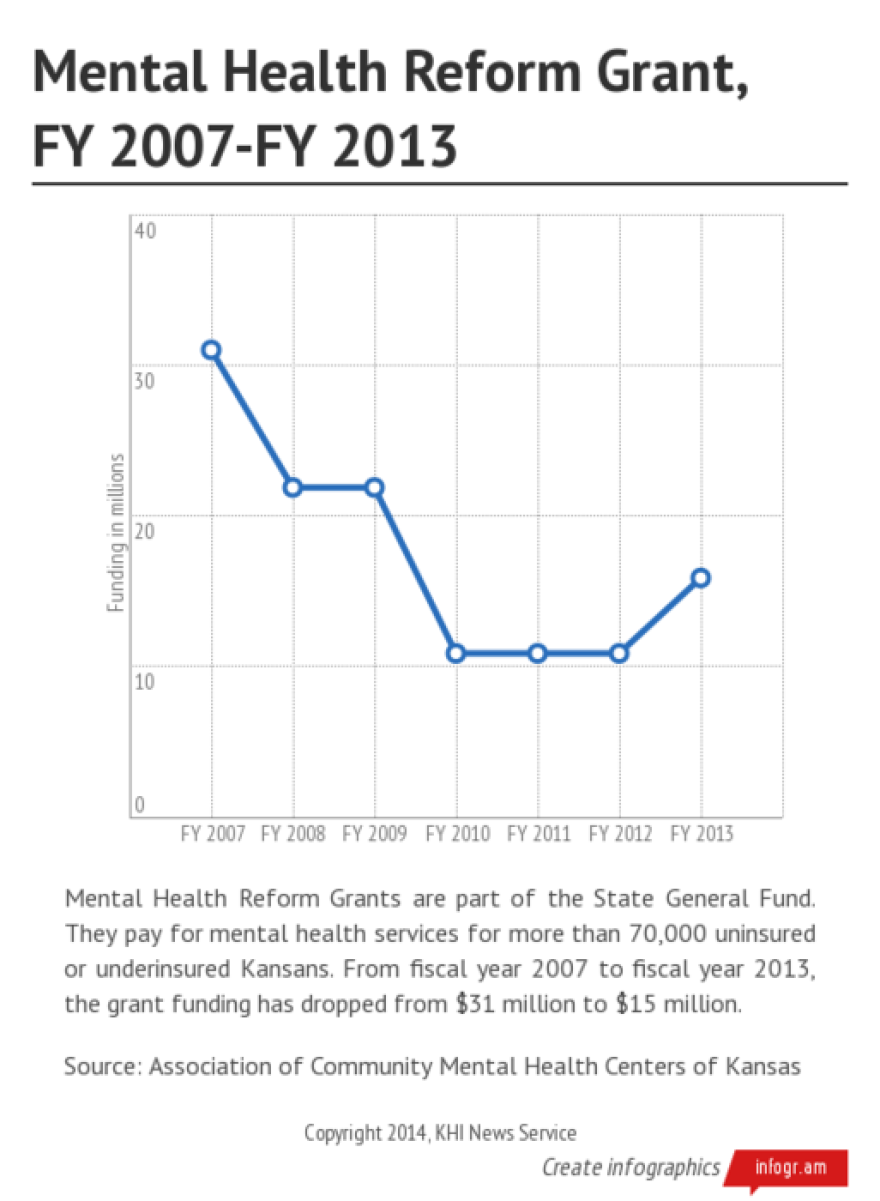

In the 1990 reform act, lawmakers created a state-funded grant program to help the centers offset their cost of caring for the uninsured. But between 2007 and 2012, the grant program’s funding fell from $31 million a year to $10.9 million.

“It pains me to say this, but when you take that much money out of a system for that many years, it’s going to have a negative effect,” says Bill Persinger, executive director at the Mental Health Center for East Central Kansas in Emporia. “That’s just the real world. There are services we used to provide that we had to quit providing because there wasn’t any money.”

Before the cuts in state spending, Persinger says, the Emporia center’s annual budget for its seven-county service area was close to $10 million. It’s $8 million now.

Before the cuts, Persinger says, the Emporia center had access to six full-time psychiatric care providers who were able to prescribe medications and monitor patients. Today, he says, he has access to three full-time providers and about half of another’s time.

“And that’s in jeopardy,” he says.

Three years ago, the center closed its two group homes for the seriously mentally ill. “We just couldn’t keep them open,” Persinger says. “We helped people find apartments and we switched to a peer-support model, which is better, but we still have encounters with people who need 24-hour supervision, and they’re not getting it.”

“We need to reopen 10 of the 20 beds we lost, but we can’t because the money isn’t there,” he says. “I can’t put any fluff on that, it’s just a fact.”

The center’s finances, he says, caused it to close its outpatient substance abuse treatment programs as well.

“Don’t get me wrong, we’ve been successful in diverting lots and lots people (from the state hospitals), and I think Kansas has a very strong community-based system in place,” Persinger says. ”But there’s more demand than there used to be, and we can’t keep up.”

Center directors also say their efforts to keep patients out of state hospitals and in their communities have been hampered by several public and private hospitals deciding to close their inpatient psychiatric units.

The Menninger Clinic closed its Topeka campus in 2003, followed by the closure of Lawrence Memorial Hospital’s 15-bed psychiatric unit in 2004. Since then, hospitals in Liberal, Coffeyville, Pittsburg and Manhattan also have shuttered their units. Cushing Memorial Hospital in Leavenworth closed its psychiatric unit just last month.

“If you go back to the late 1950s, early 1960s, there were 5,500 inpatient psychiatric beds in Kansas,” Hennen says. “Today, there are fewer than 500. That’s quite a shift in a span of 50, 60 years.”

Four County Mental Health Center, he says, has lost access to 45 private inpatient psychiatric beds.

“They’re gone,” Hennen says. The closest inpatient psychiatric unit is at Stormont-Vail HealthCare in Topeka, where he says Medicaid patients can get in if there’s an opening. For uninsured patients, he says, “Osawatomie is the only option.”

Incarceration isn’t treatment

Mental health advocates have long argued that the psychiatric unit closings and the financial challenges faced by community mental health centers are the reasons that the number of mentally ill inmates in the state’s prison system has more than doubled since 2006.

According to Kansas Department of Corrections data, more than a third of the state’s 9,600 inmates are known to have a mental illness. More than 900 are considered seriously and persistently mentally ill, a designation comparable to what’s required for admission to Osawatomie or Larned state hospital.

Neither KDADS nor the Department of Corrections tracks the number of former state-hospital patients who are now incarcerated.

“The good news, I guess, is that we’re not institutionalizing people in psychiatric hospitals like we were 30 years ago,” says Barb Andres, executive director at Episcopal Social Services, a Wichita-based program for the city’s homeless and near-homeless populations, many of whom are mentally ill.

“But the bad news is that we’re institutionalizing them in jails now,” she says.

Andres says she’s having second thoughts about the campaign to downsize the state hospitals. “I’ve worked in the mental health field for 30 years,” she says. “When I was young, as an advocate, I pushed really, really hard to close the big mental health hospitals because it was the right thing to do.

“But now when I look back and I see how we’ve got all these people in jails and prisons, I tell myself, ‘I wouldn’t do that again,’ because if we’re going to be institutionalizing people, I’d rather have them in a hospital than a jail. It really disappoints me to say that.”

Recession cuts not restored

Legislators in 2013 agreed to put an additional $5 million in the grant program that community mental health centers use to offset the costs of caring for the uninsured.

But in 2014, Gov. Sam Brownback redirected the funds to help pay for the establishment of five regional hubs to provide crisis stabilization and intensive case management to keep people with mental illness out of jail and from returning to state hospitals. The other $5 million was pulled from a fund called Family Centered Systems of Care that centers used to pay for in-crisis services for at-risk families.

“Basically, an additional $5 million got put in the system and then it got repurposed,” says Rick Cagan, executive director for the Kansas chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness. “That’s OK, that’s good, and it’s much-appreciated, but the reform grants are still way short of where they were five or six years ago.”

Last spring, Brownback proposed a $1 million increase in the grant that mental health centers used to cover the cost of providing care to uninsured Kansans. Again, Cagan says the increase was appreciated, but the amount being restored was “a drop in the bucket” compared to what was needed.

Despite what they see as an urgent need for more funding, mental health advocates fear that the best they can hope for in the 2015 budget is to hold on to what they have. Income tax cuts approved as the centerpiece of Brownback’s initiative to stimulate the Kansas economy have sharply reduced state revenue collections. As a result, legislators may be forced to cut spending when they return to Topeka in January.