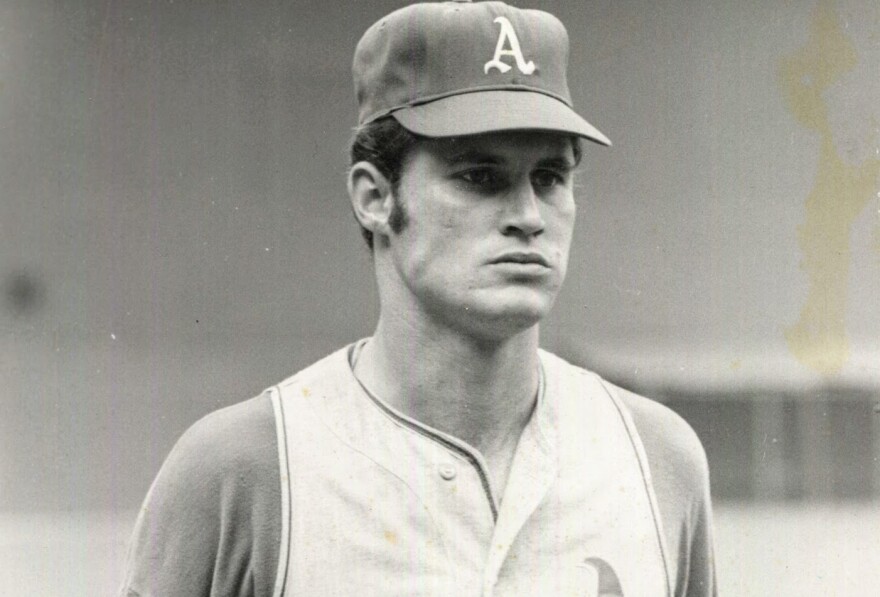

As a high school kid in Kansas City, Chuck Dobson threw heat — with the occasional control problems — pitching for the De La Salle High School boys baseball team in the early 1960s.

Yet even as a standout ballplayer, the big league Kansas City Athletics seemed so big.

On his high school ballfield, sometimes the players could hear cheers of the crowd at nearby A’s games at the now-gone Municipal Stadium at 22nd Street and Brooklyn Avenue.

But Dobson had that rare rifle-for-an-arm talent that drew the attention of scouts. He went on to play in exhibition games in the Olympics and ultimately captured the eye of future Hall of Fame manager Whitey Herzog.

He landed with the A’s and less than two hours before the team’s home opener in Kansas City, on April 19, 1966, pitching coach Cot Deal told him he’d be starting on the mound.

“‘It’s your turn, big boy.’ I said, ‘OK,’” Dobson said in a 2011 interview with KCUR. “I was nervous. I was real nervous. But nothing uncontrollable. I was OK.”

Few things compare with the excitement of pitching for a major league ball club for the first game of the season in front of home fans. Dobson was the only guy who played high school baseball in Kansas City and then threw the home opener for the pro team.

Dobson died on Nov. 30, 2021. A memorial service is set for later this month.

He’ll always be the first hometown Kansas City kid to pitch a home opener here.

The game went well. Dobson pitched nearly six innings. And he got credit for the A’s 3-2 win over the Minnesota Twins — a team that had played in the World Series the previous season.

Lew Krausse, who died last year, was one of Dobson’s best friends. He’d made his major league debut five years earlier with the A’s.

In a 2010 interview, Krausse said he knew how Dobson felt that day.

“He was as nervous as hell, man,” Krausse said. “Dobber has always been a high-strung guy anyway. But he had family and friends. This was where he was born and raised.”

Dobson hadn’t thrown a single major league pitch, yet here he was staring down a brawny Twins lineup.

“They had some thumpers. … Tony Oliva, Harmon Killebrew. You just go through that whole lineup,” Dobson said. “I’m kind of oblivious, kind of in the twilight zone out there. I’m just, ‘Let’s get the next hitter and not try to embarrass myself.’”

It meant a lot to start the 1966 home opener because Municipal Stadium was so close to where he’d grown up and played high school ball at 16th Street and Woodland Avenue.

“I used to listen to the crowd roar,” he said.

Dobson walked six batters that day. His tendency to throw wild dogged him throughout his nine years in the majors.

“Dobber will bounce it around on you,” said Ken Suarez, Dobson’s catcher in his first big league win. “But Chuck Dobson had (as) live an arm as you will ever see.”

In 1967, the A’s left Kansas City for Oakland and took Dobson with them.

In a three-year stretch, from 1969 to 1971 in Oakland, Dobson won at least 15 games each year.

Then his arm began to fail him.

“They (the A’s medical staff) operated on my arm and took a half an inch of bone off my elbow,” said Dobson. “Then I came back and tried to throw.”

Dobson missed all of 1972, then won only two more games in his final three seasons, one with the A’s (1973) and two with the Angels (1974 and ‘75).

After baseball, he met Betsy Phillips of Kansas City, Kansas. He introduced himself to her as Charles Dobson and she didn’t know at first that he was a former major league pitcher.

He wouldn’t talk about baseball — unless someone else brought it up.

“He was full of wonderful stories about baseball,” said Phillips. “He remembered everything.”

Dobson was a renaissance man after leaving the diamond. He studied history and geography and enjoyed the Kansas City Symphony. The music inspired him to buy his own violin, but he stopped short of trying to master it only a month later.

“It was too little for him to feel comfortable playing,” Phillips said.

Dobson had a range of jobs after baseball — a counselor, the owner of a house-painting business — and also devoted much of his time to volunteer efforts.

“He never met a stranger,” she said.

A memorial service to celebrate Dobson’s life is set for April 30 at the McGilley Memorial Chapel in Midtown.