LANE COUNTY, Kansas — This time of year, the wheat growing in this part of western Kansas should be thigh-high and lush green.

But as a months-long drought continues to parch the region, many fields tell a different story.

“There’s nothing out there. It’s dead,” farmer Vance Ehmke said, surveying a wheat field near his land in Lane County. “It’s just ankle-high straw.”

Across western Kansas, many fields planted with wheat months ago now look like barren wastelands. The gaping spaces between rows of brown, shriveled plants reveal hardened dirt that’s scarred with deep cracks from baking in the sun.

Of all the years for drought to hit western Kansas wheat farmers, it couldn’t have come at a worse time.

Even with wheat selling for near-record-high prices as the war in Ukraine disrupts the world’s food supplies, a lot of farmers in western Kansas won’t have any to sell. And those who made it through the drought with enough crop to harvest will likely end up with far fewer bushels than they had last year, a downturn that limits the state’s ability to help ease the global food crisis.

Wheat prices have bounced between $10 and $12 per bushel since setting an all-time record north of $13 in March. So it might stand to reason that farmers should be able to make up for poor harvests by selling the wheat they do have for more money.

But it’s not that simple.

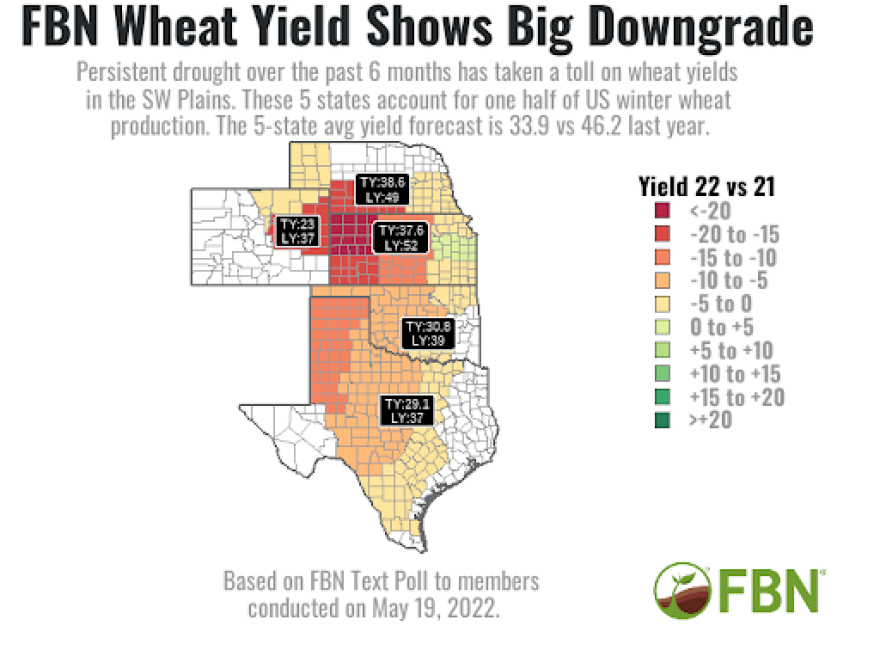

The US Department of Agriculture estimates that wheat fields statewide will average roughly 39 bushels per acre this year, down sharply from 52 bushels per acre last year. But many farms in the western half of the state will produce far less than that.

USDA projections for Lane County say wheat farmers here will end up harvesting an average of 27 bushels per acre — less than half of what the county’s farmers averaged last year.

At $11 per bushel, each acre of that average Lane County farmer’s land would bring in just under $300 this season. In order to recoup the costs of doing business, Ehmke said farmers here need to gross closer to $325 per acre.

Ehmke considers himself fortunate. He expects his wheat to end up higher than that 27 bushel average, something he credits to the way he lets his land rest between plantings. But even with conservative land management strategies, his fields might still only produce half of what they did last year — all because of too much heat and not enough rain.

And he figures that at least half the wheat fields in western Kansas won’t produce enough for farmers to break even.

“They're losing money,” Ehmke said, “even with the highest price of wheat that we've probably ever seen in the past 50 or 100 years.”

Part of the problem is an increase in costs. Farmers face higher expenses across the board this season, largely thanks to supply chain issues caused by the war in Ukraine and sanctions against Russia.

The price of diesel — the fuel required to run the tractors and trucks that keep farms going — reached an all-time high last month and remains more than $5.50 per gallon.

Nitrogen fertilizer prices also soared to record levels this spring, peaking above $1,500 per ton — more than twice what it cost one year ago.

“It’ll be a very difficult year,” Rejeana Gvillo with Farmers Business Network said. “Just because commodity prices are high, it does not mean that producers are better off.”

Gvillo, a senior commodity analyst with the national agricultural data and e-commerce platform, traveled across the state last month to survey crop conditions during the annual Kansas wheat tour.

She said the differences between wheat stands in eastern and central Kansas — areas that should still see a decent harvest this year — and western Kansas were stark.

“Shorter crop. Uglier fields,” Gvillo said. “As we drove west, it just got way worse.”

In past years’ wheat tours, Gvillo said she would wear a rain suit to walk into wheat fields because she would get soaked with dew. This year, she didn’t see any morning moisture on plants until the tour neared Wichita.

Many stands were in such bad shape that she could easily step between scrawny rows of wheat without touching the plants at all. In some of the hardest-hit areas, she found seeds lying in the dirt that never got the chance to sprout.

“It was so dry, the grass on the side of the road was dead,” Gvillo said. “And that's weeds.”

Even some of the better-looking crops in western Kansas are so short — stunted by the heat and lack of moisture — that there’s concern about whether or not combines will be able to reach low enough to harvest them properly.

And with those high diesel costs, she said, it might not be financially feasible for some farmers to run a combine over their wheat — even if the crop could produce a few bushels per acre.

Too little, too late

Kansas isn’t called the Wheat State for nothing. It produced nearly one quarter of all American wheat harvested last year.

But this year’s Kansas wheat crop has been through a lot of hardship since seeds went into the ground this past fall.

There was the Dec. 15 storm that battered the region with widespread wildfires, hurricane-force wind gusts and swirling clouds of dirt that zapped crops with static electricity and evoked images of the Dust Bowl.

Static electricity damage to wheat from dirt storm pic.twitter.com/cRmNpiGLd5

— Clay scott (@scottwestacre) December 16, 2021

This spring, extreme weather has continued to damage some wheat stands with hail, above-average winds and freezing temperatures.

Then there’s the months-long drought that continues to ring the region dry of what little moisture it has.

Every inch of western Kansas remains blanketed by some level of drought. Virtually all of southwest Kansas faces extreme or exceptional drought, the two most severe levels on the U.S. Drought Monitor’s scale. Some areas in the southwest corner of the state have been in extreme or exceptional drought since Christmas.

Even with some recent precipitation, much of western Kansas would still need an additional three to five inches of rain just to get back to its historical year-to-date average.

Most of the wheat stands in western Kansas are dryland, meaning they’re not irrigated. So growth depends on how much it happens to rain on that particular field.

But after months of wheat farmers hoping for rain, that window has closed.

“It’s basically too late for moisture to help,” Gvillo said. “In fact, water would probably hurt.”

That’s because rain would be more likely to increase the risk of disease or fungus than it would increase the yield at this late stage in the plant’s growth.

Marsha Boswell, vice president of communications with the Kansas Association of Wheat Growers, said the good news is that modern varieties of wheat seed have been bred to handle this dry climate.

“Wheat is one of the most drought-tolerant crops and one of the most resilient crops,” Boswell said. “But it does need just a little bit of help.”

The conditions this year have pushed those crops to the limit.

The US Department of Agriculture says 41% of Kansas wheat is in “very poor” or “poor” condition. That’s up from just 14% at this time last year.

The Wheat Quality Council estimates that more than one of every ten wheat fields in Kansas will be abandoned, meaning they didn’t grow enough crop to bother harvesting it. And that number is likely to creep up in the coming weeks.

“Abandonment is going to be a lot higher than an average year,” Boswell said. “There’s no way to harvest some of those acres where there’s just next to nothing left.”

Just finished up with our crop ins appraiser. Over half of our acres will not see a combine. Turns out CC wheat needs 10 lives with only 1” of precip pic.twitter.com/0eIIwe1jvC

— luke jaeger (@luke_jaeger) May 21, 2022

In other parts of the High Plains, the outlook is even more grim.

To the west in Colorado, projections say nearly one-third of wheat fields won’t produce enough to bother harvesting. In Texas, around three-quarters of the crop will likely be abandoned.

Daryl Strouts is president and CEO of the Kansas Wheat Alliance, which helps get new wheat varieties developed by Kansas State University out to farmers. If the state hadn’t already spent decades developing those drought-tolerant wheat breeds, he said, this year could have been much worse.

Kansas is still expected to harvest more than 250 million bushels of wheat this season. But that total will be down more than 100 million bushels from last year.

With record high wheat prices, that drop in production really adds up.

If you take those missing 100 million bushels and multiply them by the $11 per bushel that farmers could have potentially sold them for this year, it means the drought could cause the Kansas economy to miss out on more than one billion dollars.

“I'm always reminded of an old proverb,” Strouts said. “A farmer that has too much water has a lot of problems. A farmer that doesn't have enough water has only one.”

‘People will starve’

Now, global events have put even more pressure on Kansas wheat fields to produce food that millions of people around the world desperately need.

But even before this year’s drought, the total number of acres planted with wheat nationwide had been on a steady decline for decades as other crops like corn and soybeans became more profitable.

Two decades ago, the US produced one quarter of the world’s wheat exports. By last year, that number was down to just 13% as other countries took a larger share. Two of those counties were Russia and Ukraine, which have recently accounted for roughly one-third of the world’s wheat exports.

Now, Russia is blocking Ukraine from exporting some 20 million tons of wheat. And the war will likely prevent many Ukrainian farmers from harvesting or exporting this year’s crop.

Antonina Broyaka has seen how the Russian invasion has affected Ukraine’s communities and industries first-hand.

Until earlier this spring, she worked as dean of the agricultural economics department at the Vinnytsia National Agrarian University, just a few hours drive southwest of Kyiv. When Russia’s invasion began, she and her family fled to Kansas State University, where Broyaka studied nearly two decades ago.

She estimates that around 40% of Ukraine’s winter cropland has been lost because it’s become unsafe or is occupied by Russia.

Ukraine generally exports five to six million tons of grain per month. But most of that went out through Black Sea ports that are now blocked by Russia.

The country has still been able to export around one million tons of grain per month through rail and river transportation, Broyaka said, but that multimillion-ton deficit leaves a gaping void in the global food supply.

“Ukraine feeds around 400 million people in the world, so people will starve,” Broyaka said. “Some countries will need to replace that shortage.”

Another concern is Ukraine’s ability to store whatever grain its farmers are able to harvest this year.

Some of its large storage facilities have been destroyed by Russian bombings or left in occupied territory. Broyaka said many of the facilities that are accessible remain half-full with grain from the previous harvest that Ukraine hasn’t been able to export.

She’s also worried that Russia will continue to hold Ukraine’s wheat hostage in Black Sea ports as part of its political strategy. Russia could use that bargaining chip to blackmail nations that rely on Ukraine’s grain exports, pressuring them to support Russia’s military actions.

“That is a global problem,” Broyaka said, “and if the world will not help Ukraine to stop Russia, it will get worse.”

Recent reports warn that just 10 weeks’ worth of wheat remain in global stockpiles.

The U.S. exports more wheat than it imports, so the disruptions in Ukraine are unlikely to cause widespread food shortages here. But prices for wheat-based items like cereal and baked goods have already gone up.

For those living in countries that depend heavily on Ukrainian wheat, the consequences could be devastating. People in places like Egypt, Lebanon and Pakistan, for example, already face skyrocketing bread prices and shortages that put them at risk of going hungry.

On top of that, the world’s other leading wheat producers, India and China, have seen their crops damaged by blistering heat and overwhelming rains, respectively. Just last month, India sent wheat prices climbing yet again when officials stopped exporting the grain altogether because of worries about having enough for its domestic population.

Ernie Minton, dean of Kansas State University’s College of Agriculture, said the places most likely to be hurt by this shock to the food system are ones where millions of people already live on the edge of malnutrition.

“That is the really disturbing part,” Minton said. “The countries and the individuals that are impacted most are the ones that are least capable of shouldering that kind of shock.”

So how could the international community help? Building new grain storage infrastructure in Ukraine, Broyaka said, or investing in temporary plastic storage options — like the grain bags that K-State has been evaluating in parts of Africa — to increase Ukraine’s capacity in the short term.

Farming regions like Kansas could also help by exporting more grain. Roughly half of the wheat harvested in Kansas in a given year gets exported abroad, Minton said.

But increasing wheat production isn’t something that can happen overnight.

Here in Kansas, farmers planted their winter wheat last fall, months before Russia invaded Ukraine. So by the time global markets began feeling strained from the war, there wasn’t anything Kansas farmers could do to try to grow more, even if the rains would have allowed.

But, Minton said, that’s why K-State’s long-term research into developing new wheat varieties that can withstand future Kansas droughts is so vital.

“These are times when we really need to be cognizant of how fragile this global food issue is,” Minton said. “We all have to get involved and look for solutions, and there may not be easy ones in the short run.”

Furthermore, wheat is far from the only crop for which the world depends on both Ukraine and Kansas.

Ukraine is also one of the world’s largest corn exporters, accounting for roughly 17% of global exports. As planting time arrives for that spring grain, questions remain about how much Ukrainian farmers will be able to produce and export this year.

“Will Ukrainian farmers have access to the seeds? The fertilizer inputs? The fuel they need to run their equipment?,” Minton said. “That’s certainly a real concern.”

If drought continues in western Kansas, it is likely to limit the state’s ability to export its own corn to help make up for that deficit.

And even though this winter wheat season isn’t over yet, there are already concerns about next year.

Gvillo, the commodity analyst, said it would take superb harvests from all of the world’s major wheat producers to stabilize global supplies, and it doesn’t look like that’s going to happen this year. That would ratchet up the pressure on the 2023 wheat crop before it’s even planted.

And as the Kansas drought and Ukraine war drag on into uncertain futures, she said, global grain markets are likely to remain strained for months or even years.

“We’re not out of it yet,” Gvillo said. “I think this time next year, we’ll be having the same conversation.”

David Condos covers western Kansas for High Plains Public Radio and the Kansas News Service. You can follow him on Twitter @davidcondos.

The Kansas News Service is a collaboration of High Plains Public Radio, Kansas Public Radio, KCUR and KMUW focused on health, the social determinants of health and their connection to public policy.

Kansas News Service stories and photos may be republished by news media at no cost with proper attribution and a link to ksnewsservice.org.

Copyright 2022 High Plains Public Radio. To see more, visit High Plains Public Radio.