Kansas City is one of the top five metropolitan areas expected to experience heat index temperatures above 125 degrees in the coming decades, according to a new heat risk model. St. Louis is also on the list.

“This is sort of an emerging phenomena of days that are really off the charts of the scales that we've developed to measure these kinds of things,” said Bradley Wilson, the director of research and development at First Street Foundation, the New York-based climate research non-profit that developed the model.

The study uses land and air temperature data and climate models to predict the heat index temperatures over the next 30 years and how those temperatures will affect specific properties. It allows people to search an address and see their home’s heat risk factors.

“We're not trying to say that you're going to be boiling to death, all summer,” said Wilson. “There might be a day in the summer in your area where you know it really is not very safe to spend a lot of time outside.”

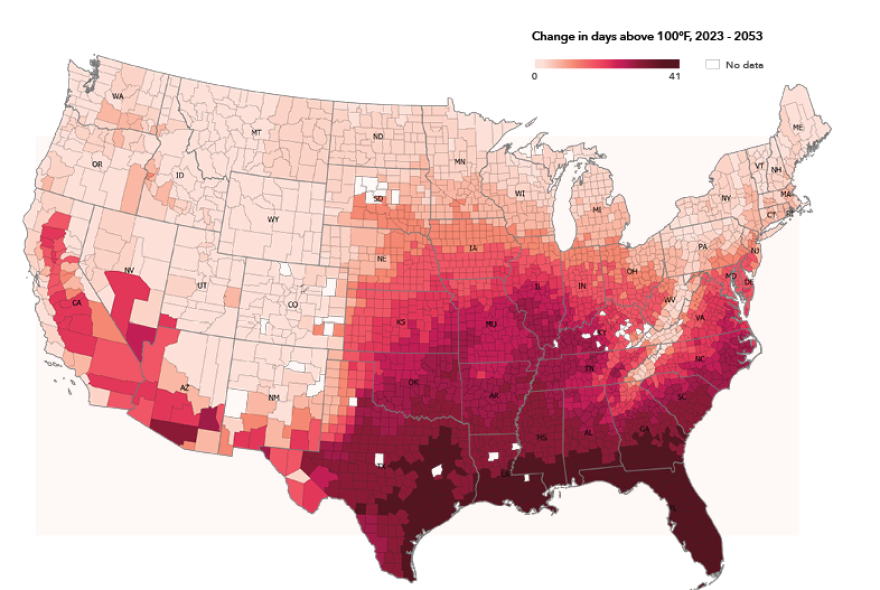

According to the study, Missouri and the eastern parts of Kansas are part of an extreme heat belt that will stretch from the Gulf Coast all the way up to southern Minnesota and Wisconsin. Kansas City is already known to be an urban heat island, and people in the metro began to feel the effects of this heat belt with high temperatures in July.

“Some of those heat waves basically formed this dome over the Midwest,” said Wilson. “The Midwest has a bunch of factors that are contributing, but at its core it's a combination of both high temperatures and humidity values that create these temperatures that feel much hotter than the actual temperature.”

Missouri is also one of the states to see a dramatic increase in the number of dangerous days — days when the heat index will surpass 100 degrees.

Some parts of Missouri will see extreme heat a lot sooner. Dunklin County, in the Bootheel, is expected to see 39 dangerous days this year. By 2053, it could see as many as 60.

These extreme heat days are a particular concern for outdoor workers and populations that are susceptible to health problems caused by heat.

“Cooling infrastructure is something that is becoming an increasing consideration in a lot of places,” said Wilson. “When you do have heat waves come through, multiple days in a row of extremely high heat, that can be a risk for vulnerable populations.”

Missouri is also one of the states estimated to have the largest increase in carbon emissions from air conditioning use, partly because of the state’s lack of green energy infrastructure. This could strain energy systems and complicate emission reduction goals.