CSU-Bakersfield men’s basketball coach Rod Barnes emerged from the locker room late last month at Municipal Auditorium in Kansas City. He was seeking a familiar face, one who gave Ole Miss its first all-African-American starting five, who encouraged him to not listen to naysayers.

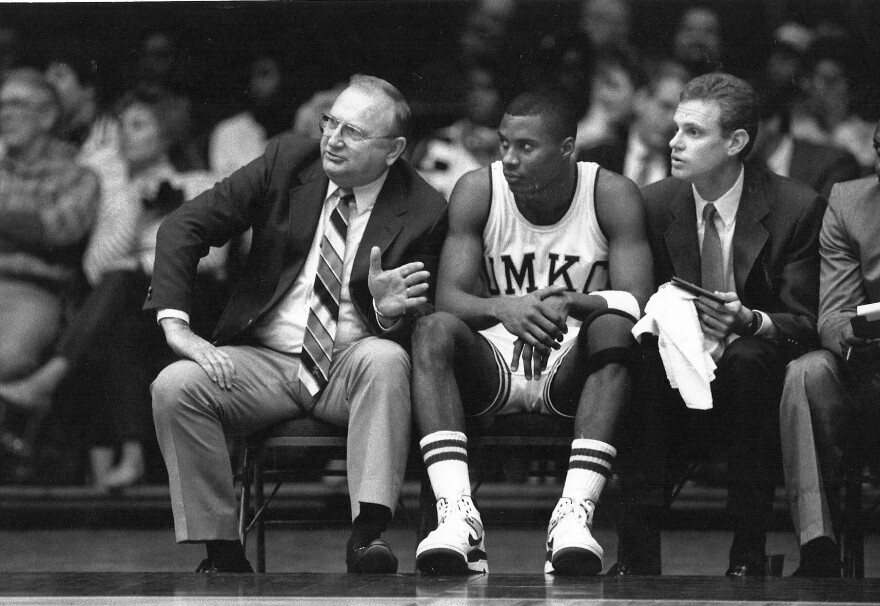

He was looking for former UMKC athletic director and basketball coach Lee Hunt, the man who was on the leading edge of race relations in high school and college sports during the Civil Rights Era. Barnes found him, exclaiming, “Coach! It’s good to see you.”

Hunt recruited Barnes to play at the University of Mississippi in the early 1980s. Just 20 years earlier, riots broke out there when a black man and war veteran, James Meredith, tried to integrate the school. Barnes says his family pressed Hunt for some answers.

“We asked him a lot of questions about the university, how the racial relations are there,” Barnes says. “How would I be put in harm’s way? Would I be treated equally and fairly? He (Hunt) guaranteed that.”

Barnes was a member of the 1984-85 team, the first at the school to have five African-American starters. It didn’t sit well with all Ole Miss fans.

“I got some hate mail because of it,” Hunt says.

On the forefront

“I’ve always had a strong feeling about this, about the way the African-American people were treated over the years,” says Hunt, who retired from UMKC in 1996.

His pushback started when he was the Warrensburg High School coach in the 1960s. One of his teams, which included a black player named Gibby Forbush, came home after a tough loss in 1962 — the same year Meredith tried to get into Ole Miss. They all wanted to grab a bite at a diner called Peterson’s.

“We went in and the manager came over and said, ‘I’m sorry, we can’t serve you. You have a black athlete with you,’” Hunt recalls. “I said, ‘If that’s the case, we’re leaving.’”

Hunt eventually became an assistant at Memphis State, now known as the University of Memphis, in 1970, which was two years after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated.

The team was good on the court, even going to the NCAA championship in 1973, where they lost to UCLA and legendary coach John Wooden. But Hunt and the rest also succeeded in lifting up Memphis, according to Jimmy Hayslip, who worked in Memphis schools for 50 years and was a scorekeeper at home games.

“They (the coaching staff) did more to bring a consolidation of whites and blacks together in this Memphis area than all the politicians combined,” Hayslip, who is white, says.

But that harmony didn’t last as the years went on, with white residents moving to the suburbs and black residents staying in the city. Memphis historian Jimmy Ogle, who is also white, says Beale Street, known now as a tourist destination, was fenced off in the late ’70s and early ’80s.

“You couldn’t walk or ride down Beale Street. Not a single business was open except for one little ol’ general store you had to enter from the alley,” Ogle says. “In 1979 is when the statistic is about more people in jail than living residentially.”

Black coaches' rise

In the national coaching community, however, there was upward mobility as more black assistants became head coaches (though the Minneapolis Star Tribune reports that trend peaked in 2005 and fell to 17 percent of major-conference teams in 2017).

Barnes joined the head coaching fraternity with a return to Ole Miss. He says Hunt never told him or his teammates about the hate mail during the 1980s, but once at the helm, Hunt warned him about what he might see.

“He (Hunt) said, ‘Hey listen, there’s going to be some people that send you mail that say things to you. But just continue doing what you’re doing,’” Barnes recalls. “’The problem is not you. It’s them.’”

Barnes’ team played in the 2001 NCAA Tournament at Kemper Arena. Hunt was keeping close tabs on Barnes, and it caught the attention of the Mississippi media.

“Rod, a few of us during your practice had a chance to visit with Lee Hunt and he said mostly nice things about you,” one reporter asked during a news conference. Barnes laughed, and the reporter continued, “Can you just comment on what he has meant?”

Barnes was clear: “I think he’s responsible a lot for me having the opportunities that I have right now.”

When Hunt looks back at his days at Ole Miss, he says he alone didn’t set out to change race relations; Ole Miss alone made a conscious effort to alter its image in sports.

“They treated the black athlete(s) extremely well,” he says. “Our athletic director stayed with one kid for six years to get his degree. That showed me that they were serious about (changing) the image that they had.”

And Hunt is thankful, because it forged the relations he has with guys like Barnes, even up until today.

Greg Echlin is a freelance sports reporter for KCUR 89.3.