As the Republican convention gets under way in Tampa tomorrow, we can expect to hear more about the personal life of presumptive GOP presidential nominee Mitt Romney. Romney aides, in fact, say that now is the time for him to " publicly embrace" his Mormon faith, a religion that plays a large role in the candidate's life but is misunderstood by many Americans.

If Romney does open up, we might get some insight into an area of particular interest to us here at The Salt — how that faith may shape his eating habits. Whether you like his politics or not, let's face it, the guy is fit. At the very least, it gives us a reason to explore the relationship between food and the Mormon religion.

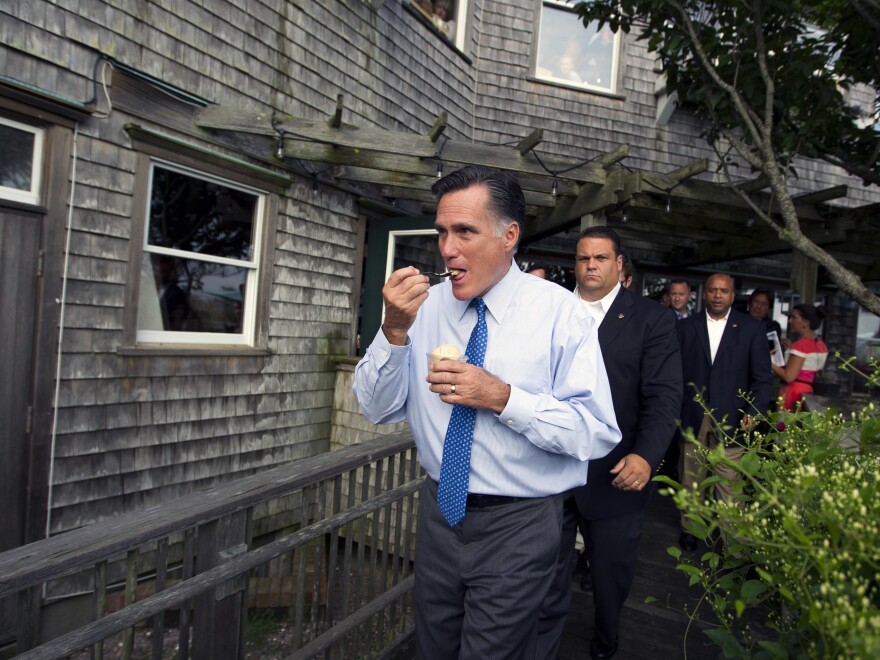

So far, we don't know much about Romney's tastes in food, aside from the occasional ice cream scooped from Bailey's Bubble in Wolfeboro, N.H., and his affection for feeding Jimmy John's subs to the press on the bus. However, parsing the eating habits of presidential candidates (to say nothing of sitting presidents) is now firmly embedded in America's cultural milieu. Just think: Ronald Reagan and jelly beans. Bill Clinton and fast food. President Obama and, well, most things chili-related, plus a bit of home-brewed beer.

We don't know if Romney adheres to it, but there is such a thing as a Mormon food culture. In fact, Mormon culinary traditions, or foodways, closely resemble the tenets of the "good food movement" currently shaping many Americans' renewed interest in food — i.e., cooking from scratch, emphasizing whole grains, and locally sourced fruits and vegetables.

Mormon foodways stem in part from the pioneer roots of Mormonism and in part from the teachings of Joseph Smith, the founder of the Mormon church, formally known as The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

According to church teaching, in the early 1830s, Smith received as revelation and dictated into lectures one of the primary texts of the Mormon faith, The Doctrine and Covenants (D&C). Section 89 of the D&C, known as the Word of Wisdom , is considered by Mormons as their law of health. In it, Smith addressed certain behaviors he wished his followers to avoid, including bans on alcohol, tobacco and " hot drinks." Mormons, therefore, do not drink alcohol or smoke, and many will not take coffee or tea.

But the diet Smith prescribed is probably less well known to non-Mormons. This includes the consumption of wheat, herbs and fruits in season, and meat " sparingly." To be clear, such a manner of eating — oracle-like for today's flexitarians — would have been logical for any people settling in the Western territories of 19th-century America. Followers of the early LDS church weren't the only ones relying predominantly on themselves for sustenance.

But additionally, Smith's followers were actually instructed to be self-sufficient — to "prepare every needful thing" in anticipation of the tumultuous world into which their church was born. (Mormons call this "provident living.") Storing food is one form of physical preparedness. Hence, the vigorous practice of canning that has marked LDS communities in the past, especially those connected to the once abundant, widespread orchards of Utah, and the "putting up" of foods culled from family gardens.

Flush with homegrown produce and the spiritual call to consume wheat, Mormon women built an enviable reputation for the quality of their pies, cakes, breads and the like — a community-specific legacy of superb baking that endures.

A Mormon woman in my town of Arlington, Mass., Saralynn Jensen, is committed to storing food and regularly incorporates whole wheat into her young family's diet from the wheat she buys in bulk and grinds at home. Her commitment to storing food and a diet high in whole wheat, fruits, vegetables and legumes is grounded in her faith, she says, but reinforced by cultural trends and accepted nutritional guidelines. Getting married "made it real," she says.

To be sure, the trajectory from past to present foodways has not been straight. Inevitably, Mormons, as did the rest of America, incorporated into their diets the processed foods readily available in the post-World War II era. We're talking canned soups, store-bought canned fruits and vegetables, boxed cereal, cake mixes, white flour, etc. — the kinds of ingredients easily stored, on hand and rendered in no time into hearty, economical, crowd-pleasing (if not always healthy) fare. In my family, my great-aunt Gladys' infamous lime Jello mold with cottage cheese and pineapple chunks stands out. Green bean casserole with fried onions also comes to mind.

For modern Mormon families, favorites might include Funeral Potatoes and a small repertoire of sweets, made mostly from processed ingredients such as Jello, pretzels and Cool Whip, that fall within the so-called bad Mormon dessert category. (Don't be fooled; they're delicious.)

But now many Americans, regardless of their faith, are looking to improve their eating habits by consuming fruits and vegetables in season and emphasizing whole grains and plant-based proteins. This sounds pretty close to the dietary ideal Mormons are called to follow.

Hopefully we'll hear more about Romney's food habits.

Sue Spinale McCrory, a native of Boston, is the former editor and host of .

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.