Amy Tan was 200 pages into a new novel when she attended a large exhibition on Shanghai life in the early 1900s. While there, she bought a book she thought might help her as she researched details on life in the Old City. She stopped turning pages when she came upon a group portrait.

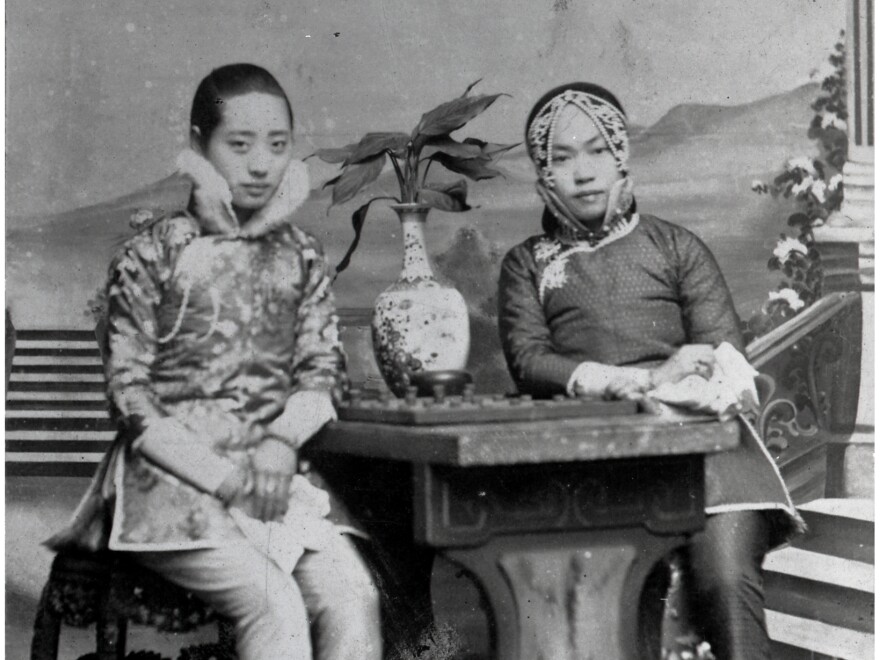

"It's called the '10 Beauties in Shanghai,' " she says. These were the winners of a citywide beauty contest for courtesans. There, staring solemnly at the reader, were 10 young women, half of them dressed in similar outfits — snug silk jackets with high, fur-lined collars and three-quarter-length sleeves that displayed long, white sleeves underneath. Several of the women were wearing tight headbands embroidered with pearls. The shape of the headbands brought the wearer's forehead to a comely V shape, and the tension pulled the eye upward, into the much-desired Phoenix eye shape. The wardrobe and the look were all part of the courtesan's official ensemble.

Tan stared at the photo. There was something about it that was disturbingly familiar.

Then she remembered a photograph of her grandmother, the long-suffering family matriarch, that she kept on her desk for inspiration. Tan's so attached to the picture, she carries a copy of the image on her mini-tablet. She pulls it out to show me.

And there, staring straight at me, is a young woman dressed exactly like the richly garmented 10 beauties.

A Picture And A Mystery

Tan says absent a diary or some other incontrovertible piece of evidence, all one can do is speculate. Family history says her grandmother married late, had two children and was widowed when her husband died in the 1918 influenza pandemic. She went to live with her brother, who, Tan says, was cheap and provided her and the children with only the barest of necessities.

Did Tan's grandmother become a courtesan because she needed the money?

Or maybe she wasn't one at all. Maybe the image reflected something else altogether. Maybe she took the daring step of entering a Western photographer's studio (where no proper young Chinese woman would ever be caught) and had her photograph taken in courtesan's clothing for shock value.

Even the most innocuous speculation, though, was too much for Tan's relatives still in China. "They were very upset that I could even bring up such a notion," she says. In deference to family peace, Tan has let it remain a mystery.

'I Never Have Trouble Cutting Pages'

Tan dumped her 200 completed pages and began again. (That's the equivalent of a modest-sized book, but Tan wasn't fazed: "I never have trouble cutting pages.") She crafted a new story of how a woman from a good family — like her grandmother — goes about making a life for herself after suddenly finding herself needing support. Back then, Tan says, "if you don't have family that are willing to take you in, you're stuck. If your family all have died in famine, or fire or political insurrection — you have nothing."

Tan's The Valley of Amazement is an opus that covers half of a tumultuous century, ranges across two continents and involves love, deceit, forgiveness and, ultimately, redemption. The novel tells the story of Lucia Minturn, a headstrong young woman from a family of bourgeois San Francisco intellectuals who meets a handsome Chinese artist under her parents' roof and falls in love. When the artist returns home to Shanghai, Lucia — abandoning all propriety — follows him. She quickly discovers he will not buck his rigidly traditional family, even though she's pregnant with their first grandchild. To support herself and her daughter, Violet, Lucia establishes a first-class courtesan house. In the chaos that follows the Qing Dynasty's collapse, Lucia is separated from Violet, and when she is of age, Violet becomes one of Shanghai's most famous courtesans.

A Deeper, Different View Of An Ancestor

There are familiar Tan themes throughout The Valley of Amazement: family estrangement, mother-daughter angst, the displaced feeling of being considered "other" in a new environment. And there is rich detail of life in the early 1900s, both in San Francisco and in Shanghai.

Her copious research gave Tan a fuller understanding of what her grandmother's daily life must have been like in China and broadened her perception of who her grandmother must have been. Her grandmother never got around to telling her own story; she committed suicide as a young woman, after what she considered an unforgivable betrayal. But Tan says The Valley of Amazementmight add another dimension to the family lore: "She was more than just a wife and a mother who cried a lot. What I imagined in my mind is whether she would have been pleased that I knew she had more gumption, more style and more attitude than the stories that had been told about her."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.