Cowardice comes in many forms, but there's a special sense of shame reserved for captains who abandon ship.

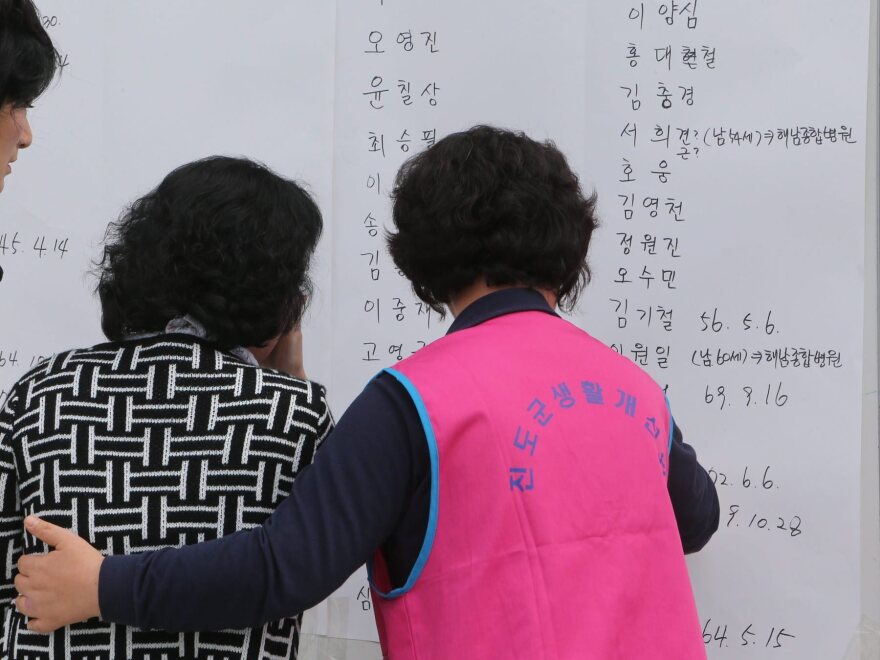

South Korean authorities have arrested Capt. Lee Jun-Seok, who was one of the first to flee from the ferry as it sank on Wednesday.

"I can't lift my face before the passengers and family members of those missing," Lee told reporters.

The incident came two years after Francesco Schettino, the captain of the wrecked cruise ship Costa Concordia, was charged with manslaughter and abandoning ship — charges he denies. The ship ran aground off the Italian coast in 2012, killing 32 people.

Has the old idea that captains should not abandon ship itself been abandoned?

"I'm kind of flummoxed that a master of a passenger ship anywhere in the world would not understand his obligation extends until that last person is safely off the ship," says Craig Allen, director of the Arctic Law & Policy Institute at the University of Washington.

The Victorian notion that a captain should actually go down with the ship has become archaic. But his or her responsibility extends to executing the evacuation plan that all passenger ships are required to have and practice.

"It comes from the tradition that the captain has ultimate responsibility and should put the care of others ahead of his own well-being in the discharge of his duties," says David Winkler, program director with the Naval Historical Foundation.

Women And Children First

In the middle of the 19th century, there were a number of incidents in which ships foundered and captains and their crews were either celebrated for leading the rescue or reviled for saving themselves while passengers drowned.

One of the most famous involved the HMS Birkenhead, which wrecked off the coast of South Africa in 1852 while transporting British troops to war.

"The captain called the men to attention," says William Fowler, a maritime historian at Northeastern University. "They were to stand at attention on the sinking ship until the women and children — their wives and children — were led off the boats."

The moment was immortalized by Rudyard Kipling as the "Birkenhead drill." Reinforced when Capt. Edward Smith went down with the Titanic, the notion that a captain must stay with his ship became part of folklore.

"A lot of this is candidly still more lore than law," says Miller Shealy, a maritime law professor at the Charleston School of Law.

A Breach Of Duty

In the U.S., case law indicates that a ship's master must be the last person to leave and make all reasonable efforts to save everyone and everything on it.

"It is not just unseemly for a captain to leave a ship," Shealy says. "In Anglo-American law, you would lose your license and make yourself liable."

After Capt. Chesley "Sully" Sullenberger crash-landed a flight in the Hudson River in 2009, he twice walked the plane to make sure no one was left onboard before leaving himself.

International standards for sea captains vary. Often, as in the case of Schettino, charges are brought based not on dereliction of maritime duty but for offenses that might pertain on land as well, such as negligence and manslaughter.

In 1991, Capt. Yiannis Avranas not only abandoned the Greek cruise ship Oceanos after it suffered an explosion off the coast of South Africa but cut ahead of an elderly passenger to be hoisted aloft by a helicopter.

"If the master is simply looking out for himself or herself, you've breached your duty both legally and morally, to your ship, your crew and your passengers," says Allen, the University of Washington law professor.

Part Of The Culture

In last year's Star Trek Into Darkness, the bad guy taunts Captain Kirk by saying, "No ship should go down without her captain."

The image of a captain staying with a sinking vessel has recurred again and again, in literature and real life. It remains so potent because of the almost mythic authority invested in ship captains, Allen suggests.

At sea, there's no question about who's in charge, so there's no doubt who is responsible for safety.

"His duty as the highest authority available short of God himself was to make sure his crew was safe before he left the ship," says Craig Symonds, a retired Naval Academy historian.

The sense that captains are beyond the law — that they are the law, or at least they were, during the age of sail — is why they make such great bad guys.

"When they go bad, they're evil," Shealy says.

Think of Bligh, or Queeg, or the autocratic captains who drive many of the novels and stories of Herman Melville.

In Moby-Dick, Captain Ahab sets off to hunt the whale, leaving the capable Starbuck in charge. When his "death-glorious ship" sinks, Ahab mourns that he's been denied the "pride" of having gone down with her.

"Ahab is a great example in the sense that he knows a captain should go down with his ship," says Wyn Kelley, a Melville scholar at MIT. "He deeply regrets not being with his crew."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.