Finding an address on a map can be taken for granted in the age of GPS and smartphones. But centuries of forced relocation, disease and genocide have made it difficult to find where many Native American tribes once lived.

Aaron Carapella, a self-taught mapmaker in Warner, Okla., has pinpointed the locations and original names of hundreds of American Indian nations before their first contact with Europeans.

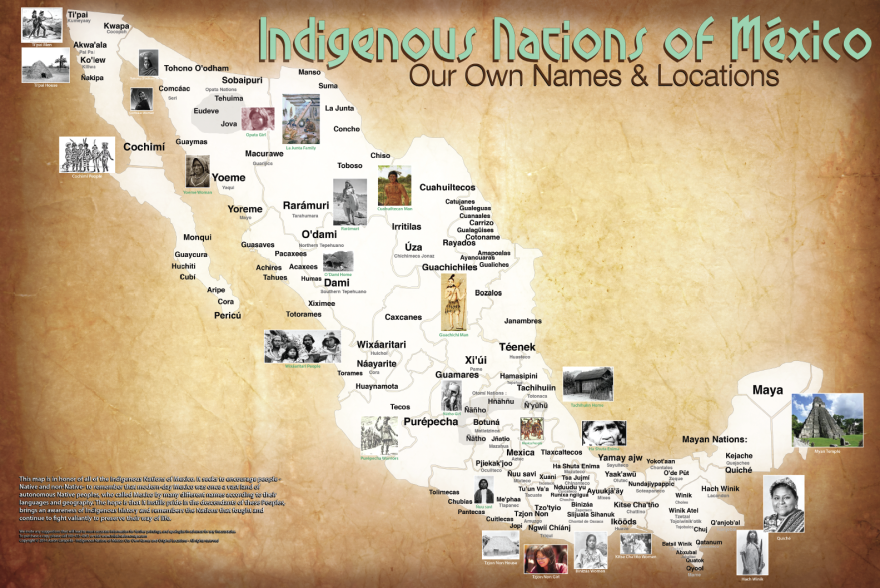

As a teenager, Carapella says he could never get his hands on a continental U.S. map like this, depicting more than 600 tribes — many now forgotten and lost to history. Now, the 34-year-old designs and sells maps as large as 3 by 4 feet with the names of tribes hovering over land they once occupied.

"I think a lot of people get blown away by, 'Wow, there were a lot of tribes, and they covered the whole country!' You know, this is Indian land," says Carapella, who calls himself a "mixed-blood Cherokee" and lives in a ranch house within the jurisdiction of the Cherokee Nation.

For more than a decade, he consulted history books and library archives, called up tribal members and visited reservations as part of research for his map project, which began as pencil-marked poster boards on his bedroom wall. So far, he has designed maps of the continental U.S., Canada and Mexico. A map of Alaska is currently in the works.

What makes Carapella's maps distinctive is their display of both the original and commonly known names of Native American tribes, according to Doug Herman, senior geographer at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C.

"You can look at [Carapella's] map, and you can sort of get it immediately," Herman says. "This is Indian Country, and it's not the Indian Country that I thought it was because all these names are different."

He adds that some Native American groups got stuck with names chosen arbitrarily by European settlers. They were often derogatory names other tribes used to describe their rivals. For example, "Comanche" is derived from a word in Ute meaning "anyone who wants to fight me all the time," according to the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

"It's like having a map of North America where the United States is labeled 'gringos' and Mexico is labeled 'wetbacks,' " Herman says. "Naming is an exercise in power. Whether you're naming places or naming peoples, you are therefore asserting a power of sort of establishing what is reality and what is not."

Look at a map of Native American territory today, and you'll see tiny islands of reservation and trust land engulfed by acres upon acres ceded by treaty or taken by force. Carapella's maps serve as a reminder that the population of the American countryside stretches back long before 1776 and 1492.

Take a closer look at Aaron Carapella's map of the continental U.S. and Canada and his map of Mexico . He sells prints on his website .

Carapella describes himself as a former "radical youngster" who used to lead protests against Columbus Day observances and supported other Native American causes. He says he now sees his mapmaking as another way to change perceptions in the U.S.

"This isn't really a protest," he explains. "But it's a way to convey the truth in a different way."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.