They call it "The Hummus Wars."

Lebanon accused the Israeli people of trying to steal hummus and make it their national dish, explains Ronit Vered, a food journalist with the newspaper Haaretz in Tel Aviv. And so hummus became a symbol, she tells us, "a symbol of all the tension in the Middle East."

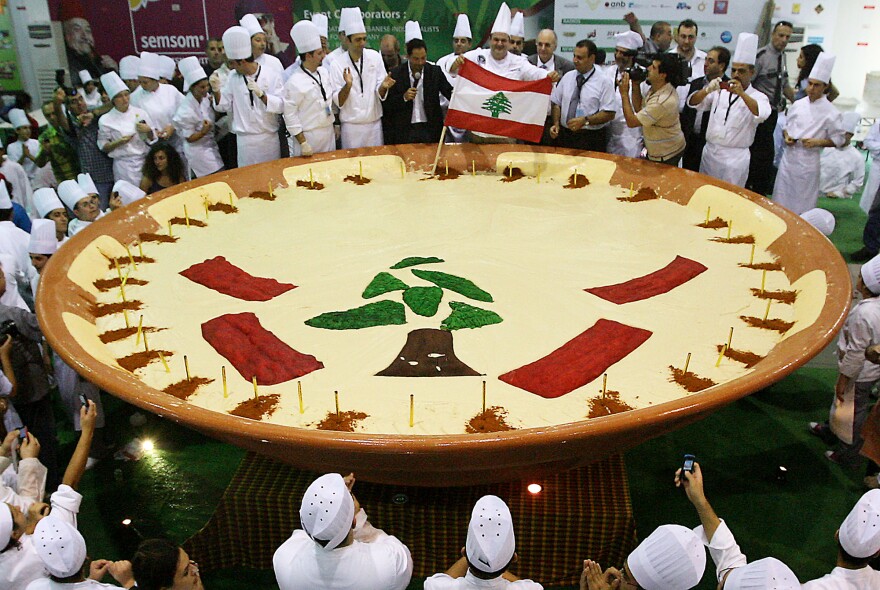

The war began over a 4,532-pound plate of hummus.

In 2009, Fadi Abboud — the minister of tourism -- led Lebanon to break the world record for making the largest tub of hummus in the world. At the time, Abboud was also chairman of the Lebanese Industrialists Association. "A group of us just came from a food exhibition in France. There they were telling us that hummus is an Israeli traditional dish," he says. "I mean, the world now thinks that Israel invented hummus."

Abboud could not let that stand. "I thought the best way to tell the world that the hummus is Lebanese is to break the Guinness Book of Records."

At the ceremony, when Guinness awarded Lebanon the prize for its epic plate of hummus, Abboud announced, "We want the whole world to know that hummus and tabouli are Lebanese, and by breaking [into] the Guinness Book of World Records, the world should know our cuisine, our culture."

The event was big news all over the Mideast region. "It was [a] big issue that hummus was Lebanese," says Jawdat Ibrahim, an Arab-Israeli entrepreneur and owner of the popular Abu Gosh restaurant in an Arab village of the same name near Jerusalem. "I said, 'No, hummus is for everybody.' "

And so, "I hold a meeting in the village and I say, 'We are going to break Guinness Book of World Record.' Not the Israeli government, the people of Abu Gosh."

When they did just that, in January 2010, the news was broadcast around the world. "In the town of Abu Gosh this morning, Israel retook the title for the world's largest hummus dish, weighing 4 tons and served in a satellite dish," one news announcer intoned.

"Yes," Ibrahim recalls, "a satellite dish. It's a dish, no?"

It drew more cameras than when Obama visited the country, Ibrahim says.

Within hours, the Lebanese planned a counterattack -- and within months, they presented the world with a vat filled with 23,042 pounds of hummus.

At the time, Abboud says, Lebanon was also trying to register the word "hummus" with the European Union, with a protective designation of origin — in the same way Champagne is registered by France, Parmigiano Reggiano by the Italians, and the Greeks lay claim to feta cheese. Abboud was asking the EU to ban any country other than Lebanon from calling their product hummus. The Lebanese Industrialists Association called its campaign "Hands Off Our Dishes."

"The word for chickpea in Arabic is hummus," says Abboud, who has been studying the history of hummus for some time now. "So the actual name comes from the Arabic for chickpea."

But in the end, the EU did not allow Lebanon to register hummus as its own, because it is the food of an entire region.

'The Hummus Is Our Tradition'

That region includes Israel.

Vered, the food journalist with Haaretz, has been chronicling the arc of Israeli food and cooking for years.

Since the country is only 68 years old, and its citizens came from all over the world, it lacked a unifying food tradition. So hummus became a common ground for Israelis.

"Palestinians also made hummus a symbol," Vered notes — a symbol "that we didn't only take their land, we took their food as well and made it ours."

Palestinian Nuha Musleh agrees. "The hummus is our tradition. Tabouli is our tradition," says Musleh, who works as a fixer with international journalists and owns a rug and antiques store in Ramallah.

We travel with Musleh from Jerusalem to the West Bank and Ramallah. After a long wait at a checkpoint while making the crossing, Musleh stops her SUV at one of her favorite restaurants in Ramallah so we can taste Palestinian hummus. "People run to get hummus when they are in Ramallah," she says. "It's like getting a good pizza in downtown Rome. Or getting a good T-bone steak in Texas, I imagine — I haven't been."

The restaurant owner, Ali Abu Anas, leads us into his kitchen, where plates of hummus piled with radishes, pickles and sumac are being made. "What distinguishes any hummus from another is nafs — which is 'soul' in Arabic," he says. Here, they pound the hummus by hand.

"They pound it, they pound it, they pound it. They don't use a machine," he says, as Musleh translates for us. "They use good tahini, sesame seeds crushed, sumac, lemons from Jericho, olive oil from the Hebron hills." He tells us that Palestinians don't mind that Lebanon is proud of its hummus, or that Egypt makes hummus as well. This is a dish that brings Arabs together.

But this same dish that unites Arabs doesn't always have the same effect between Palestinians and Israel.

"In the first two decades of the state, the Israeli people didn't really eat local food. They stuck to their old habits," Vered explains. "It's also a political issue. If I eat Palestinian food, in a way, I acknowledge that they exist, that there are other people here who have food of their own."

By the late 1950s, the Israeli army started serving hummus in mess halls, and soon the average Israeli came to know hummus as an everyday food.

As the local fare became more familiar to the Israeli immigrants from Europe, hummus became hip, something young people began to eat, says Dafna Hirsch, a sociologist at the Open University of Israel in Tel Aviv and author of the article " Hummus is best when it is fresh and made by Arabs."

"Hummus became appropriated as the food of the new sabra," she says, using the term for an Israeli Jew born in Israeli territory, someone rooted in the land. "In Israel, hummus is considered a masculine dish," says Hirsch. "It's a kind of masculine ritual to go with a group of men to the hummusiya and eat hummus, wiping with these large circular gestures."

These days hummus isn't merely a dish -- it's a subculture, says Shooky Galili, a young Tel Aviv entrepreneur who runs hummus101.com. The blog features recipes, reviews and recommendations for hummusiya, or hummus joints. There's a community around hummus, he says.

But Musleh -- the Palestinian woman who has been showing us around Ramallah — is far from taken with the subculture that Galili and many Israelis are feeding.

"Hummus, unfortunately, has become in the category of fast foods," Musleh says. "But actually in [the Arab world] and all of Palestine, hummus is a Friday honorable breakfast. The father wakes up in the morning, makes hummus, makes food, invites all his daughters and daughters-in-law and sons. It's a way to get together in the morning of a Friday, when the family wants to throw all their worries and problems away."

'Food Is Maybe The Only Thing That Gets People To Sit Together'

As Musleh drives us back to Jerusalem, back toward the checkpoint, she explains, "there's usually congestion, because there's the refugee camp on left, a village called Qalandia on the right, and there's no man's land, Kufr Aqab. You have 130,000 people using one road."

As we get closer, we notice the rug merchants and food vendors who have set up makeshift businesses along the crawling route. "I never think of eating breakfast on days when I have to go through the checkpoint," Musleh says, "because, look, there's a kebab stand and there's vendors selling ka'ak, the bread with sesame and za'atar." These vendors do a big business. "Because you're stressed, you need something. You could get shot. The checkpoint could close. You could get a gas bomb. Suddenly you're not a human being. The kitchen of the checkpoint is really crucial to connect people together as human beings," Musah says.

Back in a cab in Tel Aviv, we notice the tattoo on our taxi driver, David Varon, and ask, "What does it say?"

" 'No fear,' " he says. "Some people are afraid to live in a country where there is so much blood and wars and conflict over thousands of years. You cannot live in fear in Israel." Because, he adds, "this conflict is about religion, and it will not be over until religion is over." He drives, and continues, "Hummus and falafel — food is maybe the only thing that gets people to sit together."

Most of the hummus makers at the hummusiyat we visited in Israel -- Lena's in Jerusalem, Abu Hassam in Tel Aviv, Hummus Said in Akko -- echoed Varon's thoughts.

But Dafna Hirsh from the Open University of Israel isn't buying it. "This kind of approach says, 'Oh, if we eat together, peace will come through the stomach.' But no. As long as colonization continues, as long as occupation continues, then hummus is not going to solve it." Many of the Palestinian hummus makers we spoke with expressed similar sentiments.

Still, Jawdat Ibrahim has a vision -- a kitchen vision.

Ibrahim grew up in poverty in Abu Gosh, an Arab living in an Arab village in Israel. He came to America in his early 20s with just a quarter in his pocket, then won a $23 million lottery in 1973 in Chicago and returned to his village in Israel to open his hummus restaurant. "We broke the Guinness world record, but to make hummus is not the issue. To put people together, that is the main thing. People talk about blood and killing, and I want to take it to a different way," he says. "People can talk about the Middle East about nice things, not killing and shooting."

The Hummus Wars continue. But, Ibrahim says, "Nobody gets hurt with this war."

Recipe: Basic Hummus

This recipe comes courtesy of British-Israeli chef and restaurateur Yotam Ottolenghi, who grew up in Jewish West Jerusalem, and his business partner and co-chef Sami Tamimi, who grew up in the Muslim neighborhoods of East Jerusalem. It is excerpted from Jerusalem: A Cookbook.

This hummus is smooth and rich in tahini (sesame paste), just the way we like it.

Makes 6 servings

1 1/4 cups dried chickpeas

1 teaspoon baking soda

6 1/2 cups water

1 cup plus 2 tablespoons light tahini paste

4 tablespoons freshly squeezed lemon juice

4 cloves garlic, crushed

6 1/2 tablespoons ice cold water

Salt

The night before, put the chickpeas in a large bowl and cover them with cold water at least twice their volume. Leave to soak overnight.

The next day, drain the chickpeas. Place a medium saucepan over high heat and add the drained chickpeas and baking soda. Cook for about three minutes, stirring constantly. Add the water and bring to a boil. Cook, skimming off any foam and any skins that float to the surface. The chickpeas will need to cook for 20 to 40 minutes, depending on the type and freshness, sometimes even longer. Once done, they should be very tender, breaking up easily when pressed between your thumb and finger, almost but not quite mushy.

Drain the chickpeas. You should have roughly 3 2/3 cups now. Place the chickpeas in a food processor and process until you get a stiff paste. Then, with the machine sill running, add the tahini paste, lemon juice, garlic, and 1 1/2 teaspoons salt. Finally, slowly drizzle in the ice water and allow it to mix for about five minutes, until you get a very smooth and creamy paste.

Transfer the hummus to a bowl, cover the surface with plastic wrap, and let it rest for at least 30 minutes. If not using straightaway, refrigerate.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.