GARDEN CITY — As a nurse, Betsy Rodriquez interviews teenagers who are sexually active and often shockingly ignorant about sex.

“So if I sit here and ask a teenager, ‘Have you had oral or vaginal sex,’” Rodriquez said, “some of them cannot tell me what oral or vaginal sex is.”

Few places in Kansas, much less the country, draw people from so many places and such dire circumstances. From one apartment complex to the next block, the dominant language can change — dozens of times.

But while immigrants and refugees that man the region’s beefpacking plants often come from places that lack modern health care, it’s far from the only contributing factor. There’s drug abuse, sex trafficking, gaps in sex education classes for teens and a laundry list of cultural taboos all leading to an environment where gonorrhea, syphilis, chlamydia and, now, HIV spread quickly.

Rising STD rates

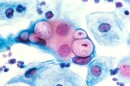

Since 2015, sexually transmitted diseases have climbed in Kansas along with national rates. A 2017 study from the Centers for Disease Control noted a rise of syphilis, including among the newborns of infected mothers.

More gonorrhea cases were reported, and the report states that’s particularly worrisome because the agency is “running out of treatment options to cure” emerging strains of drug-resistant gonorrhea.

Kansas Department of Health and the Environment Secretary Lee Norman, a physician, said the state saw nine cases of babies who contracted syphilis from their mothers in the womb in 2018. That congenital syphilis can cause developmental delays — even death — in newborns.

For a decade, Norman said, there were no reported cases of congenital syphilis. Within the last several months, he said, “we had a pair of twins born both with congenital syphilis and both died.”

From January to June 2019, Finney County has seen a higher rate of reported chlamydia cases than it did during the same period in 2018.

In 2017, Kansas Health Matters compiled the state’s STD data, which showed Finney County having the second highest rate in the state behind Wyandotte County.

Rodriquez said that new HIV infections are also on the rise.

“A lot of people believe that HIV and syphilis aren’t a thing anymore, but they’re both coming back,” she said. “There are different risk factors for these things, but it applies to everybody — it doesn’t just apply to men having sex with men or bisexual people or transgender people.”

Finney County HIV rates rose from zero to four new cases in 2018.

“To have four new cases identified in 2018 in a small county like Finney,” Norman said, “is troublesome.”

Drug use and the sex trade

Risky behaviors such as unprotected sex and needle sharing still contribute to new infections. Norman said the uptick in opioid and methamphetamine use tracks with the escalation of HIV and syphilis cases.

“Health is not top of mind,” Norman said. “Access to drugs is top of mind.”

Norman said trading sex for drugs isn’t new, but it’s particularly common among people who are poor and mentally ill.

“You talk about, you know, somebody that’s having three or five sexual contacts a day, when they themselves are infected, just in order to get their drugs,” he said. “That’s a public health nightmare.”

Anytime a patient admits to using drugs to Garden City physician Racquel Stucky, she makes sure that patient is tested for STDs. And she worries whether the person might be forced to sell sex for money.

“A lot of times, you’re kind of looking back and you’re like, ‘Oh, my goodness, I wonder if that person is involved in that and will they ever come back and will I ever be able to step in and help in a way?’” Stucky said.

Uncomfortable conversations

Garden City public schools teaches one unit of reproductive health in English in both middle and high school. The classes are abstinence-based. Students’ parents can opt their kids out of those classes.

“Abstinence is the only 100% effective way to prevent pregnancy or the spread of sexually transmitted diseases,” Superintendent Steve Karlin said.

Students are taught about methods of contraception. But Karlin said they are not taught how to use condoms.

Despite rising STD rates, the number of pregnancies among 10- to 19-year-olds in Finney County dropped from 145 in 1995 to 45 in 2018.

Forty languages are spoken in Garden City schools, but reproductive health is taught only in English. Norman said materials should be provided in different languages.

Sister Janice Thome with Dominican Sisters Ministry of Presence has served people from 26 countries in her 22 years with the ministry.

“In most of the countries that our immigrants and refugees come from, you only go to the doctor when you’re sick,” she said. “There’s no such thing as a well-baby checkup or whatever.”

Before coming to the U.S., immigrants and refugees undergo a physical and mental health screening by a doctor, said Rosa Norman, a spokeswoman for the CDC. The checks include tests for leprosy, gonorrhea, syphilis and tuberculosis.

“These are considered inadmissible conditions under federal regulations and must be treated prior to U.S. arrival,” the CDC official said in an email.

Stucky speaks Spanish and uses a phone translation service. Still, she said translating medical terms may feel invasive to some of her patients.

“Even with a translator, you were saying, ‘You know, do this or use a condom.’ And that might be socially, culturally, just not even a thing that you’re allowed to do,” she said.

Stucky, Lee Norman and some state legislators want to attack the problem more aggressively. If a person tests positive for an STD, they want the freedom to treat their sex partners even if they’ve yet to be infected. That approach, called expedited partner therapy, is illegal in Kansas.

A bill approving the treatment passed in the Kansas House this year, but stalled in the state Senate.

“If they have chlamydia, it will be treated,” Norman said. “If they don't have chlamydia, they haven't done themselves any harm.”

Corinne Boyer covers western Kansas for High Plains Public Radio and the Kansas News Service. You can follow her on Twitter @corinne_boyer or email cboyer (at) hppr (dot) org.

The Kansas News Service is a collaboration of KCUR, Kansas Public Radio, KMUW and High Plains Public Radio focused on the health and well-being of Kansans, their communities and civic life.

Kansas News Service stories and photos may be republished at no cost with proper attribution and a link to ksnewsservice.org

Copyright 2020 High Plains Public Radio. To see more, visit High Plains Public Radio.