A leukemia drug may have cleared another hurdle as a potential treatment for Parkinson's disease.

But critics say it's still not clear whether the drug, nilotinib (brand name Tasigna), is truly safe or effective for this use.

In a study of 75 people with Parkinson's, nilotinib appeared to improve quality of life and boost the chemical dopamine, a team from Georgetown University Medical Center reported Monday in JAMA Neurology.

"We are seeing signals that this may be a potential treatment for our Parkinson's disease patients," says Dr. Fernando Pagan, director of the medical center's movement disorders program.

But other scientists are less positive about the results.

"They really didn't find anything convincing," says Dr. Joel Perlmutter, who directs the movement disorders program at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

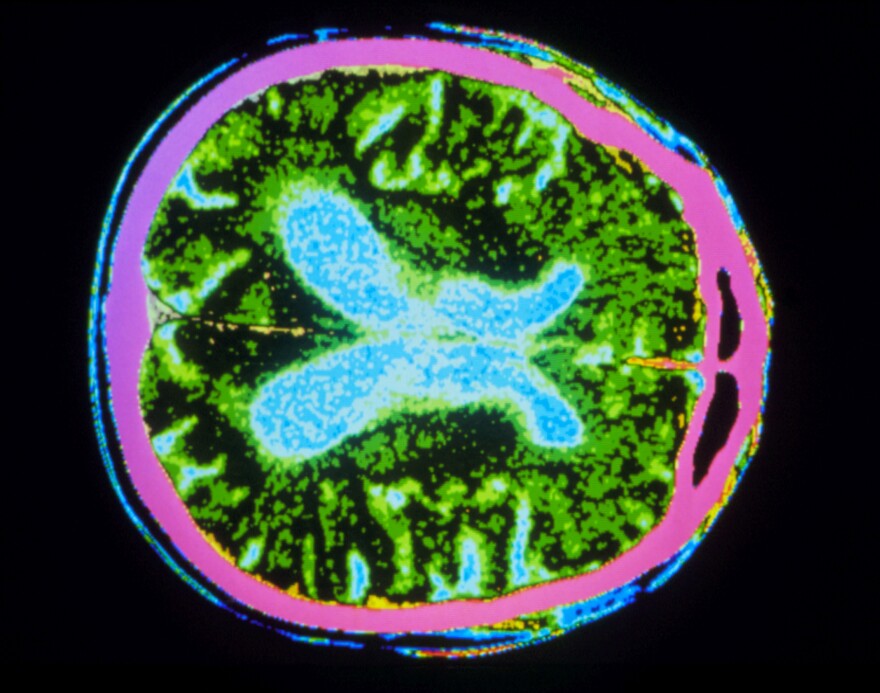

Parkinson's is a nervous system disorder that causes movement problems including stiffness and tremors. Existing drugs can treat those symptoms, but not the underlying loss of brain cells that causes the disease.

Several years ago, a team at Georgetown began studying nilotinib as a way to treat Parkinson's and other brain diseases, including Alzheimer's.

The drug appears to help brain cells clear out toxic substances that build up in those diseases.

When patients take nilotinib, "You turn on the garbage disposal daily and you're able to get rid of that accumulation and hopefully see better function," Pagan says.

Results of a small, preliminary study looked promising. So the Georgetown team launched the larger, more rigorous second-phase study of 75 people.

In the new study, some Parkinson's patients took either 150 milligrams or 300 milligrams of nilotinib each day for a year, while others received a placebo.

The results suggest that the drug is reasonably safe for these patients and may even be slowing down the disease, Pagan says.

Samples of spinal fluid showed that patients who got the 150-milligram dose of the drug had lower levels of a toxic form of the protein alpha synuclein, which tends to build up in people with Parkinson's.

The study also found some evidence that nilotinib raised levels of dopamine, the brain chemical that is lacking in people with Parkinson's.

"Nilotinib is increasing the availability of stored dopamine in the brain," says Charbel Moussa, scientific and clinical research director of the translational neurotherapeutics program at Georgetown University. "So the brain is now extracting its own endogenous stores of dopamine."

Perlmutter isn't so sure.

It's not clear from the study whether the dopamine changes were caused by nilotinib or something else, he says. And other seemingly positive results looked good at one point in time but not in another.

"It's possible these are really statistical aberrations and are not really convincing evidence of a change induced by the drug," he says. "But we don't know."

Perlmutter is also concerned about side effects, including heart problems, which were more frequent in people who got the drug than those who got a placebo. Nilotinib is known to cause heart problems in some leukemia patients.

The Georgetown study represents the latest exchange in an ugly scientific conflict over the use of nilotinib for Parkinson's.

The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research has publicly criticized the Georgetown research — even as it was conducting its own study of the drug.

And a week ago, the foundation put out a press release saying that nilotinib didn't help Parkinson's patients in their study — even though results of that study haven't been published.

Moussa, who holds a patent on the use of nilotinib for treating brain diseases, says patients should ignore the scientific infighting.

"This may fail. It's OK," he says. "But I think the concept is very feasible and if this drug doesn't work, another drug will work."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.