Until now, all the pictures of the sun have been straight-on head shots. Soon, scientists will be getting a profile.

NASA and the European Space Agency are set to launch a joint mission on Sunday to provide the first-ever look at the sun's poles. Previous images have all been taken from approximately the same angle, roughly in line with the star's equator.

Scientists are hesitant to guess what the elusive poles of the star might look like. "I hate to speculate," says Holly Gilbert, the NASA project scientist for the mission.

"We're constantly taken by these discoveries where we thought we knew what something would be before we measured it for the first time," says David McComas, an astrophysics professor at Princeton University. "And then we go like, 'Oh, geez, that's really different than we expected.' So, I think we want to keep an open mind about that."

After the NASA/ESA probe called Solar Orbiter takes off from Florida's Cape Canaveral, it'll use Venus and Earth's gravity to propel itself outside that equatorial plane where all the planets in our solar system orbit the sun. Orbiter eventually will be able to look down onto the poles of the sun.

There are many reasons why scientists want to know more about the sun's poles. They think the poles might be driving some important aspects of space weather throughout the solar system, which can impact spacecraft and even humans on Earth. "It has real world effects on our satellites, our GPS, our power grid and things like that," McComas says.

"As we get more and more technologically advanced, the more susceptible we are to space weather and the more important it becomes to be able to forecast and hopefully ultimately predict," Gilbert says. The data that Orbiter collects could eventually help build models forecasting space weather.

The mission will map the sun's magnetic fields from the poles. Scientists think these fields have a complicated relationship with what's happening inside the sun.

Since the 1800s, scientists have noticed that the sun goes through cycles between points of relative calm and high activity. The active times are associated with "a lot of sunspots, a lot of flares, and solar storms," Gilbert says. These cycles happen roughly every 11 years.

Scientists don't fully understand what causes these cycles. But they've noticed that they line up with major changes in the sun's magnetic field. One pole is positive and one is negative — and every 11 years, the poles swap and have the opposite charge.

Gilbert says the changing polarity is likely because of activity inside the sun. "It's a very complicated, rotating ball of gas and that causes the magnetic fields to get all tangled up." The fields store magnetic energy, which can escape in the form of solar storms when the fields get snarled. It's a chaotic process that can result in the poles switching polarity.

It would be useful for scientists to better understand when the biggest flares are going to happen, in order to protect satellites and other spacecraft. "Even though we have ideas about how many sunspots and how many storms and how often they might occur, we can't really predict how strong they're going to be," Gilbert says.

The Solar Orbiter will also be able to collaborate with another probe circling the sun. NASA's Parker Solar Probe launched in 2018 and will eventually come within 4 million miles of the sun's surface — far closer than this new mission. It will move through the sun's corona, a super-hot aura of gases around the star, and gather data on its magnetic fields and energetic particles, as NPR's Nell Greenfieldboyce has reported.

At certain points, the Solar Orbiter will be positioned along the same magnetic field line as the Parker probe. Gilbert says this means they'll be able to measure particles at two different times — once at Parker and then once again when they reach the Solar Orbiter. "We're going to have a nice picture of evolution of some of these particles and how that flow is changing as it's moving away from the sun," she says.

McComas, who is involved in the Parker mission, says he's excited to be able to look at the solar wind from two different latitudes at that same time. That solar wind blasts the sun's magnetic field in all directions, which can create the space weather bursts that interfere with satellites and GPS.

"We almost always measure it from this one perspective in the equatorial plane," he says. Having these measurements from two perspectives will allow them to determine whether the perspective that we've always known is representative – or as he explains, maybe they'll say, "Gee, it's really different when you get to be, you know, 30 degrees higher."

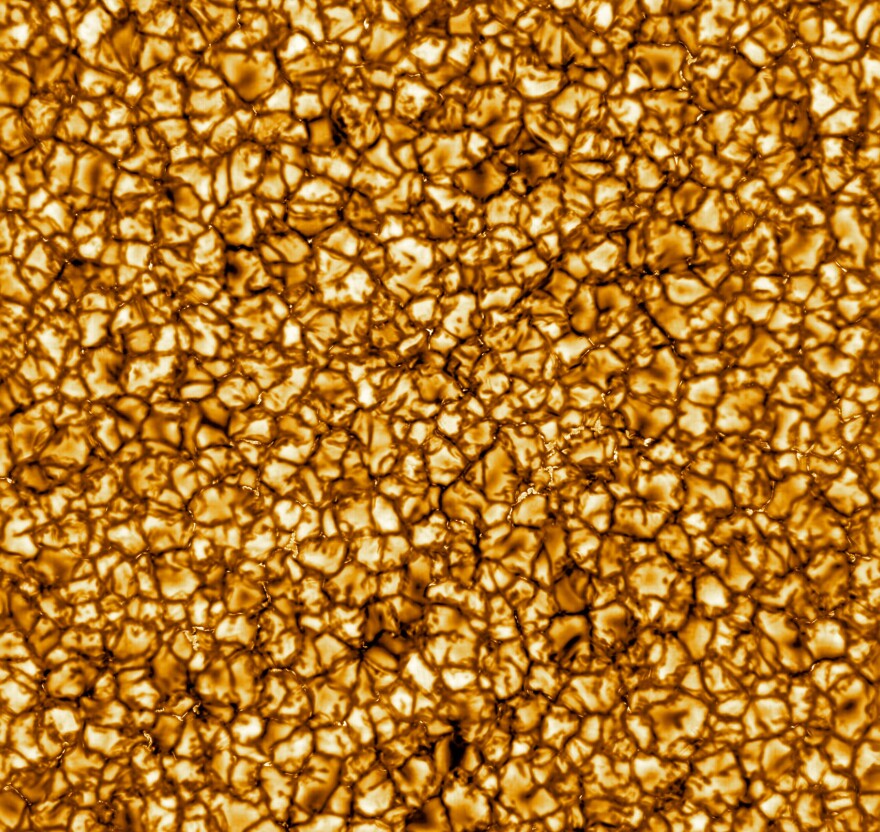

It's worth noting that scientists are also getting unique views of the sun from the National Science Foundation's Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope. Last month, the foundation released unprecedented, mesmerizing photos of the sun's surface.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.