WICHITA, Kansas — Little did city leaders know what they were setting in motion when they decided in the early 1930s to widen the Arkansas River downtown to prevent flooding.

The decision meant the end of Ackerman Island, which sat on a sandbar in the middle of the river. And the end of Island Park, the baseball stadium there.

In 1934, Raymond "Hap" Dumont helped convince city officials to build Lawrence Stadium, promising to hold a national baseball tournament there if they did.

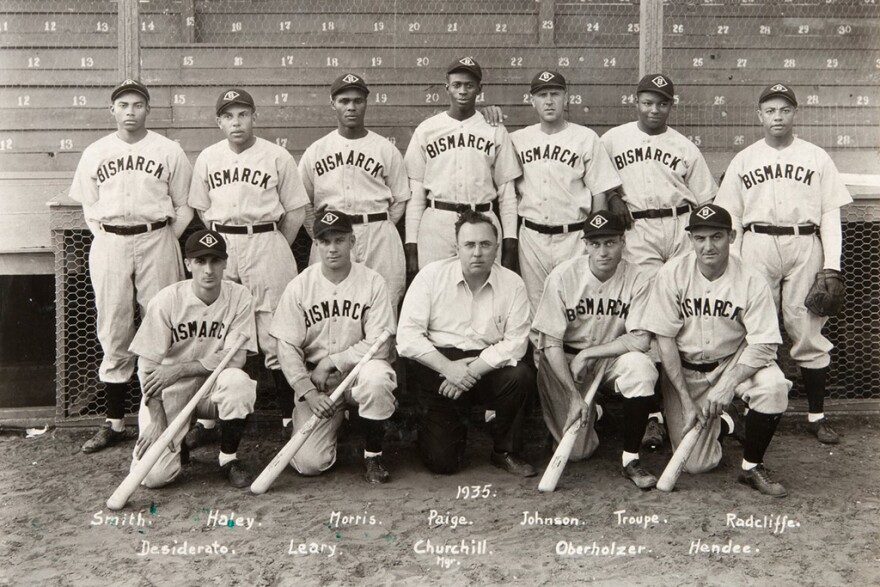

And for that first National Baseball Congress event in 1935, Dumont lured Leroy "Satchel" Paige and his team from Bismarck, North Dakota, as the featured attraction.

Nearly 100 years later, the NBC is still running. And Paige has become perhaps the most significant player in Wichita's long baseball history.

He was the star of that first tournament, winning four games, striking out 60 batters, leading Bismarck to the championship, and, most importantly, drawing large crowds.

The tournament was a huge success, drawing more than 100,000 fans over 16 days, including 10,000 for the championship game.

"Paige was recognized at that point as certainly a drawing card," said Tom Dunkel, who wrote a book about Paige and the Bismarck team, "Color Blind: The Forgotten Team that Broke Baseball's Color Line."

"And that played out in Wichita. If you looked at the attendance figures for that first tournament, they were getting almost double the crowds for those games that Paige was pitching."

Bill Kentling worked with Dumont as the NBC's vice president of marketing in the early 1970s. He said Paige set the tournament on a path for success.

"There is no question in my mind that if the first tournament fails, there is every likelihood there is not a 1936 national (tournament)," Kentling said.

"It put the National Baseball Congress on a map larger than just Wichita, Kansas."

Dumont had promised Paige's team $1,000 just to play in the tournament, more than double what the average worker earned in 1935. The team won another $2,500 by knocking off the Halliburton Cementers of Duncan, Oklahoma, in the title game.

Paige struck out 14 that night and also drove in a run with a single.

"It supposedly took Paige a half hour to get off the field after the game cause he was swarmed by so many people and kids who wanted autographs or a chunk of his uniform," Dunkel said.

"So clearly, the Paige mystique was already in high gear at that time, and he was very much the life of that 1935 tournament."

Despite his starring role in the first NBC tournament, Dunkel said Paige's performance in Wichita had a historical significance that ran much deeper.

Bismarck had both Black and white players, a rarity in 1935. And that drew the interest of Branch Rickey, who was general manager of the St. Louis Cardinals.

Ten years later, Rickey — by then president of the Brooklyn Dodgers — would sign Jackie Robinson, major league baseball's first Black player.

"Rickey, being the savvy baseball man that he was, was keeping his eye on that tournament and seeing, 'Well, how are people reacting to having Blacks and whites playing on the same field?' And then you even have one situation with the Bismarck team where they were playing on the same team," Dunkel said. "So that tournament, I think, definitely raised both Paige's profile and opened the door to the possibility of the major leagues being integrated."

Paige would eventually become part of that integration movement, joining the Cleveland Indians in 1948. That same season, he became the first Black player to pitch in the World Series.

Over the following decades, Paige was a regular visitor to Wichita. He played here with various barnstorming teams and even pitched in the NBC tournament in 1960 at age 54. Paige would continue to play baseball well into his 60s.

He also came back several times as a baseball celebrity and ambassador.

In 1971, Paige was the first player selected by a special Negro League committee to join the baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

A year later, he came to Wichita to throw out the first pitch at the NBC and put on a pitching exhibition between games. Kentling said Paige was a national icon by then but had remained good friends with Dumont.

"He had genuine affection for Dumont because he understood what Ray Dumont and what that tournament had meant to his own career," Kentling said.

During his appearance, Kentling said Paige was mobbed by fans.

"By that point in his life, Paige understood his role as a celebrity," Kentling said. "Part of the deal was he was going to stand for a lot of pictures. He was going to sign autographs. Because he wasn't Satchel Paige, the great right-handed picture anymore. He was Satchel Paige, the celebrity. But he adapted to that very, very well and embraced it.

"I cannot tell you how many kids who had never seen Satchel Paige play wanted his autograph."

Paige died in 1982 in Kansas City, Missouri, where he had spent many years playing with the Monarchs of the Negro League.

Kentling said Paige's contributions to baseball in Wichita transcend any other player.

"It's incalculable what this one man meant to the city of Wichita, " Kentling said. "And when you tie his legacy to Dumont, I would argue that they are the two most influential people in the history of baseball, not just in Wichita, but I would say Kansas.

"And the fact that the universe put them together for one summer, and that here we are 50 years later talking about it, answers your question about the influence that he had."