A photograph of murdered Chief Big Foot, his body twisted in the snow, is among the most famous images in the history of the American West. U.S. Cavalry troops killed the Lakota leader and more than 200 other American Indian men, women, and children at Wounded Knee on South Dakota's Pine Ridge Indian Reservation on Dec. 29, 1890. Traveling reporters and photographers captured the scene and its aftermath, making it a national news event.

The famous photograph of Big Foot, along with another picture showing his corpse in the snow, are among 60 in a new exhibit at the Kansas City Public Library that's as painful as it is mesmerizing.

Thanks to the library's collection and his own decades of research, organizer Eli Paul provides additional context to the well-known story.

Paul, who co-wrote Eyewitness at Wounded Knee in 1991, took over as manager of the library's Missouri Valley Special Collections in 2011. Looking through the collection, one photograph caught his eye.

"It's not a very exciting scene: a group of soldiers standing behind barricades," he says. "The original caption is 'Indian fighting at Pine Ridge.'"

It might not be an exciting scene, but it's the kind of discovery that excites serious historians.

"I have seen hundreds of photographs taken by this set of itinerant photographers before and after Wounded Knee, but this was one view I had not seen anywhere else before. I was pleased to discover there were 15 original vintage prints in the collection taken at that time."

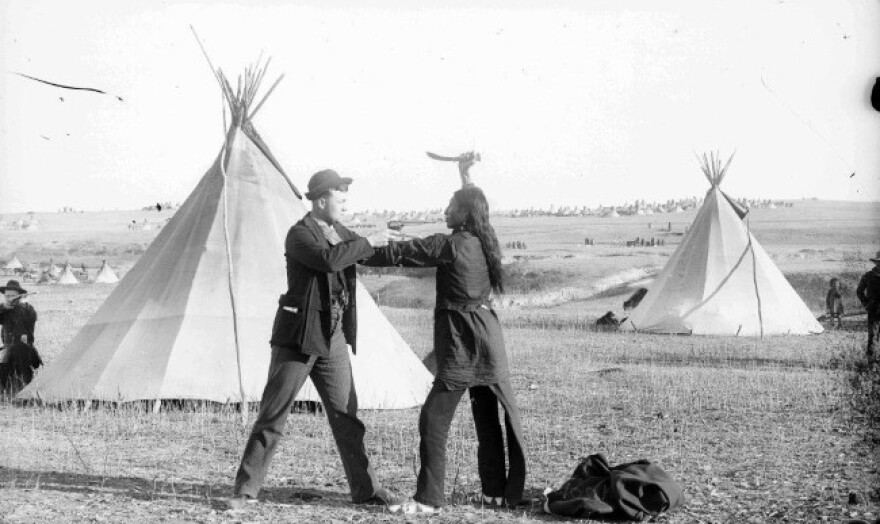

These photographs from 1890-91 are significant because they show tepee villages, scenes within the town of Pine Ridge, and some of the iconic views taken on the site of the massacre, Paul says.

The Kansas City Public Library is not particularly well-known for its American Indian collection. But, Paul says, librarians there have been interested in American Indian history since Colonel Daniel B. Dyer and his wife Ida amassed a collection originally located in the library. (The Dyer Collection ultimately grew to more than 2,000 pieces managed by the Kansas City Museum.)

"About this time last year I noticed that 2015 was going to be the 125th anniversary of Wounded Knee, and I wondered what people were going to do about it," Paul says. "Then I thought, why don’t we do something about it? We have the photographs, a great gallery, and the time to do an exhibit. I like to show that Missouri Valley Special Collections goes beyond just Kansas City and has things relating to the American West."

The Kansas City Public Library's small photographs are in a display case in the middle of this exhibition. Surrounding them on the walls are photographs on loan from the three main repositories of similar historic images: the Nebraska State Historical Society, the Denver Public Library and the Library of Congress, which all have easily accessible digital collections.

Thanks to some of their original glass-plate negatives, Paul says, "the degree of detail you can see now on some of these prints is amazing, the things in the background that I’m now looking at – we're getting whole batches of new information out of them."

To design the exhibition, Paul worked with the library's exhibitions manager, Anne Ducey. He's pleased with the response to what he calls "one clever thing we did that's really caught people's attention" — a section of the exhibition subtitled "Lies, Damned Lies and Photographs," about the absurd subterfuges of 1890s photojournalism.

"This is a brutal topic. It’s not something I would necessary recommend anyone spending all their time on," Paul says of Wounded Knee research. "Even in that situation there are somewhat amusing instances in which the photographer is basically lying to his customer. I've always been interested in them because they do teach a nice lesson: People can’t trust everything they see. A picture might be worth a thousand words, but 500 might be a lie."

That's the case with the famous photograph of Big Foot. In a newspaper article at the time, a reporter traveling with the burial party described how the image was made.

"Big Foot lay in a sort of solitary dignity," the reporter wrote. "He was dressed in fairly good civilian clothing, his head being tied up in a scarf. A wandering photographer propped the old man up, and as he lay there defenseless his portrait was taken."

They may have had a different idea of journalistic standards, but photographers understood their role in history, Paul says.

"They did have an idea they were producing really iconic images that basically say it all about Wounded Knee or the Indian wars or the treatment of the American Indian in the 19th century: The photograph of the guys beside the wagon filled with bodies, the photograph of the common grave where people are standing around with the bodies, either of the two images of Big Foot."

It took some time, Paul notes, before the public recognized that what took place at Wounded Knee was not a "battle," as government officials portrayed it.

"Those photographs prove that as a lie," Paul says. "It took photographs to convince the world that it was the Wounded Knee Massacre. You really have to be a troglodyte to refer to that scene as a battlefield."

Even though the 125th anniversary of the massacre isn't getting as much attention as the centennial, Paul's proud the library has recognized it.

"The people in Pine Ridge obviously remember it. Every year there's a Chief Big Foot commemorative ride they do no matter what the weather, and it’s usually horrendous on Dec. 29. They are still remembering."

C.J. Janovy is an arts reporter for KCUR 89.3. You can find her on Twitter, @cjjanovy.

Frozen in Time: Images of Wounded Knee and Pine Ridge, 1890-91, through March 13 at the Kansas City Public Library, 14 West 10th Street, Kansas City, Missouri, 64105, 816-701-3400.