Joe Jones doesn’t sound like the name of a great artist – it sounds like the name of a house painter, which is what Jones was during his early days in St. Louis. But an exhibition at the Albrecht-Kemper Museum in St. Joseph argues that Jones' name deserves to be as well known as his regionalist contemporaries: Thomas Hart Benton, John Steuart Curry and "American Gothic" painter Grant Wood.

Or Edward Hopper, if Hopper would have painted fewer lonely urban coffee drinkers and more Dust Bowl agricultural workers. Consider Jones' "Farmer With a Load of Wheat," an oil painting depicting the man from behind – we can't see his face; all we know about him is what kind of hat he's wearing and that he's strong enough to shoulder a burlap-type bag of grain – staring ahead at a horizon darkened with factory smoke.

"This one is painted really during the height of the Depression – 1936 is one of the worst years of the Depression, especially in the Midwest," says Albrecht-Kemper Museum director Brett Knappe. "Perhaps he’s lost his farm, perhaps he’s now working as a day laborer. We don’t know exactly what his story is, but clearly it’s a story of struggle, a story of poverty, a story of difficulties of life."

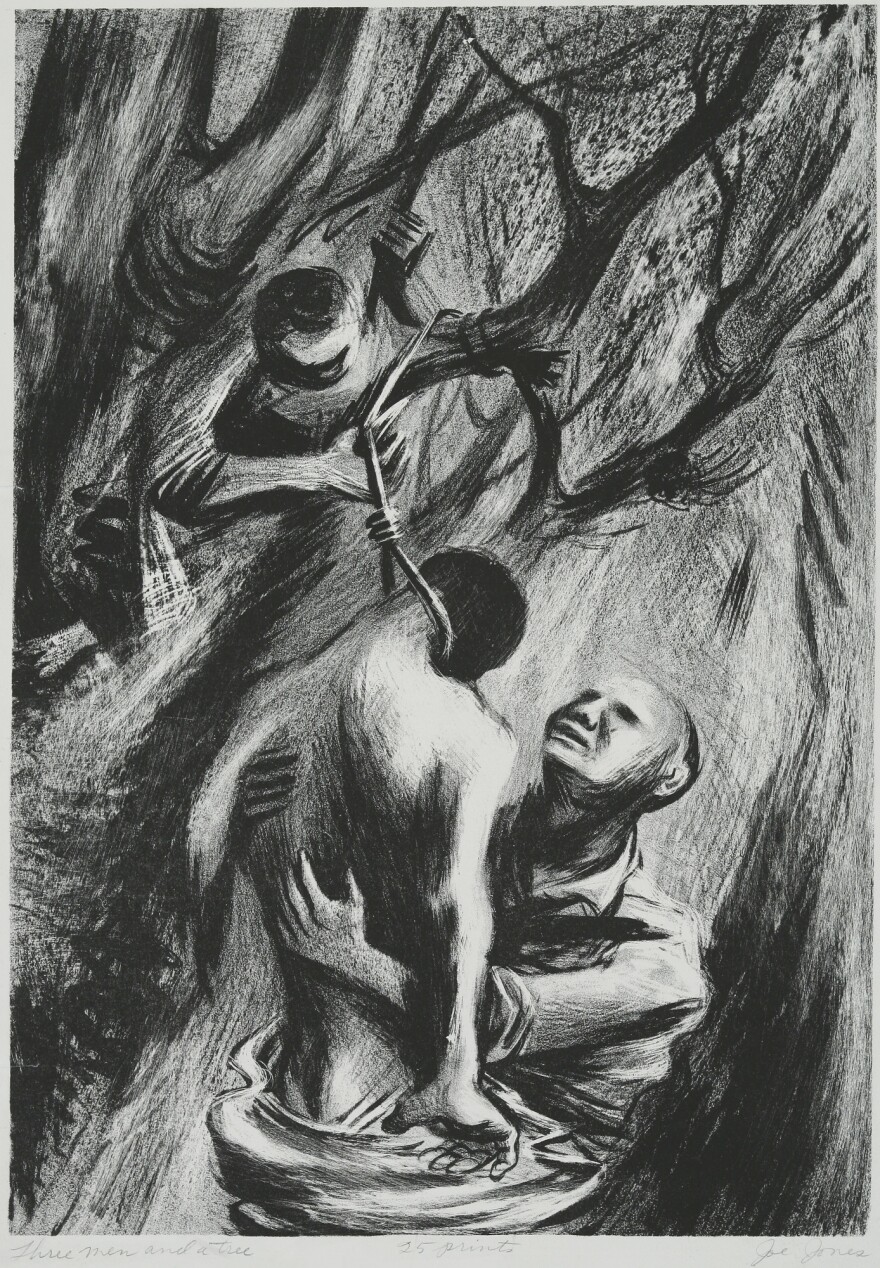

A few walls away is a more intense work of social commentary. "Three Men and a Tree," from 1937, is a black and white lithograph of a lynching scene. A father pulling his son down from a tree.

"It’s the body language, it’s the facial features that really tell the story," Knappe says. "The incredible emotional pain in this period, not just for the family, not just for the community, but the incredible pain that we feel for the nation when we see horrors that happened earlier in our history."

It may be the resurgence of those types of horrors that's generating new interest in Jones. But if that's the case, audiences might miss another important phase of the artist's career, according to Kansas City art collectors James and Virginia Moffett.

The Moffetts own about 40 of Jones’ paintings, prints and lithographs. It’s their collection that’s on view at the Albrecht-Kemper, along with another 20 pieces on loan from other museums and galleries.

"He said a lot on paper and on canvas that grabbed me," Virginia Moffett says. "He talked about the suffering of people during the Depression. And then he moved beyond that, and went to a calmer, quieter time."

A Midwesterner first

Joe Jones was born in St. Louis in 1909. While working with his father as a house painter, he taught himself to paint pictures, and did well enough that a group of patrons got together to send him to an artists’ colony in Provincetown, Massachusetts.

"And instead of getting all the training and classes everyone expects," Knappe notes, "he becomes a communist instead."

He ended up in New York, where his shows got rave reviews. During the Depression, he earned Works Progress Administration commissions to paint post-office murals that still exist in Missouri, Kansas and Arkansas.

And after swearing that even as a Communist he'd never had any intention of disrupting the American government, Jones was among the painters in an official War Art Unit who deployed to various theaters during World War II. Their charge, from the U.S. Army Chief of Engineers, was to "record the war in all its phases; and its impact on you as artists and as human beings... the nobility, cowardice, cruelty, boredom of war; all of this should form part of a well-rounded picture."

When he returned home to the East Coast, his art was different. So were his politics. In 1957, Jones would write in a letter to a friend that his belief in Communism had ended nearly two decades earlier.

"I don't see what is to be accomplished by me saying I hate the Communist Party while there are so many other things I hate at least as much," he wrote.

"Joe Jones wasn’t the only one who was one thing before the war and another one after," says James Moffett. "The world changed."

An ocean painter second

By the late 1940s and '50s, Jones was making lyrical landscapes, peaceful boats in placid harbors.

"Abstract expressionism comes into play, so the whole art world is transitioning at that point to art for art’s sake, and pure color and form and line, completely devoid of social content," notes Cori Sherman North, curator at the Birger Sandzén Memorial Gallery in Lindsborg, Kansas, as well as the curator for the Moffetts’ collection. She did extensive research to write the essay in the exhibition’s catalog.

"That's what was popular at that time, and I would say that Joe Jones was certainly affected by that whole mileau of the art world changing and no doubt he wanted to change with it," says North.

This work also earned critical acclaim and sold well. So the Moffetts thought it was unfortunate when the St. Louis Art Museum did a major Jones exhibition in 2010 and didn’t include this phase of his career.

"We feel he got short-changed in St. Louis," Jim Moffett says.

"We wanted people to see the Missouri wheat farmers, the fisher women in Alaska," Virginia Moffett adds. "We wanted them to see how far he took it."

"He was a good artist and well-respected at the time," Jim says, "and when he died, all of a sudden, 'poof.'"

"It wasn’t too long after his death in 1963 that people started forgetting his work and what he’d accomplished," says North. "Even in his own town, where he settled in Morristown, New Jersey. They did a retrospective exhibition of the area and he was barely a footnote."

The Moffetts say they hope the Albrecht-Kemper brings Jones some of the attention he deserves. So does one recent visitor to the museum: the artist's son, Jamie Jones, who brought his family to St. Joseph for the show.

In the end, an American painter

As his wife, Karen, and daughters Elizabeth Grace and Katherine toured the exhibition, the younger Jones told stories prompted by pieces he recognized – and considered whether to make the hour-long drive west to Seneca, Kansas, where his father painted a post-office mural he'd never seen.

"I’m just so proud of my father's work," Jamie Jones said. "There are things here I haven’t seen before, some things I've seen things many times. I'm always amazed at how good he was, how varied the work is, how wonderfully he chronicled what our country was going through at a very difficult time and the variety of the subject matter."

Jones was 12 when his father died, but because Joe Jones had a studio in the big carriage house where they lived in Morristown, Jamie Jones has vivid memories.

"He didn’t go away in the morning to New York City to work like a lot of my friends’ fathers did, so he was always around," Jamie says. "I had a lot of contact with him, he was very affectionate, he loved me and I loved him. He was continually working at the easel, painting, and I was very influenced by his personal presence and his values. He taught me the importance of following your dream, letting the creative forces of the world have their way in your life."

The younger Jones says art historians have told him there are periods when artists will be forgotten and then times when they'll be rediscovered and rise to prominence, which is what seems to be happening now. He says he’s getting more requests to reproduce his father’s work. Maybe because of its earlier themes.

"To be struggling with poverty, or injustice, racial injustice especially — those are the sort of things that got the attention of my father at a very young age, and people are rediscovering them. I think the mood of the country is changing and there’s an interest in these things," he says.

But whether he’s looking at a political piece or something impressionistic, Jamie Jones says that familiaity always gives him the same feeling.

"Every time I look at a painting or print or lithograph or watercolor that my father did, I feel peace within me because I feel close to him. And it reminds me of the world that I've known all my life, which has always been his artwork and what it represents," he says. "So every time I see Joe Jones, I feel a sense of contentment and peace within myself. After all, he was my father."

What’s interesting is I’d never heard of Joe Jones, and I feel the same way.

The Restless Regionalist: The Art of Joe Jones, through September 10 at the Albrecht-Kemper Museum of Art, 2818 Frederick Avenue, St. Joseph, Missouri, 64506; 816-233-7003. The museum is extending its hours on Saturday and Sunday, August 19 and 20, for visitors coming to St. Joseph for the solar eclipse.

C.J. Janovy is an arts reporter for KCUR 89.3. You can find her on Twitter, @cjjanovy.