In search of gold, the first Spanish conquistadors arrived in Kansas in 1541. Though they were disappointed, the age of discovery is still alive and well for a Kansas State University scholar named Patrick Dittamo, who has recovered a treasure of the Renaissance.

It’s a piece of music that Kansas City audiences will be the first to hear in nearly 500 years, and the first to hear outside the Sistine Chapel.

Dittamo is a graduate student in composition and musicology. He first encountered the music of the Renaissance in college at William & Mary, then kept up his enthusiasm for early music while he served in the United States Army and continued his studies at K-State. Last summer, he attended Yale’s Historical Notation Bootcamp.

“There are plenty of pieces from the Renaissance that are still in manuscript,” he says. When he learned the Kansas City Chorale wanted to resurrect a piece from the era, he says, “I went rummaging and I came across a somewhat obscure Spanish composer, Bartolomé de Escobedo.”

Escobedo lived from around 1505 to 1563. He spent a little over 14 years as a singer with the Sistine Chapel choir. (When Escobedo arrived in Rome in 1536, Michelangelo was just starting his work on the fresco “The Last Judgement” that adorns the altar wall).

Though few of Escobedo’s works have survived, in his time he was well regarded for both his composition and his voice. His appointment to the Sistine Chapel choir caused a ruckus: He was the second Spaniard admitted, and his appointment was by a special decree from the Pope, though that went against the rules of the self-governing choir, which auditioned and selected its own members.

He also had a temper, incurring fines for insulting his fellow choristers, and was even excommunicated in 1546 and absolved the next day.

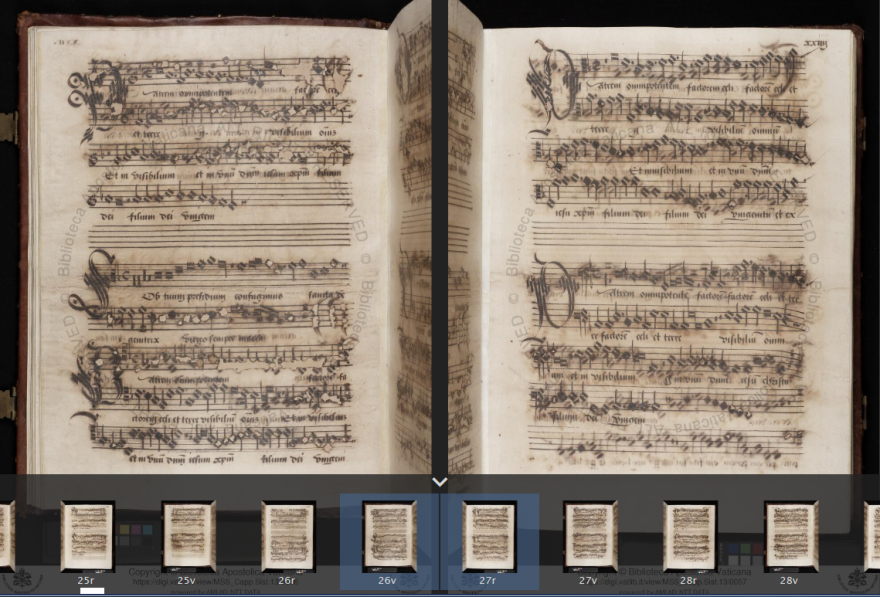

Escobedo’s “Missa Ad te levavi” exists in only one record, a manuscript copied out around 1540 by the Vatican’s official scribe. It’s in poor condition, written with oak gall ink (derived from the ball-like growths created by wasp infestation), a highly acidic substance that corroded the paper.

“Centuries of storage without humidity or temperature control has led to a great deal of ink bleeding,” Dittamo says.

Fortunately, the Vatican Library had digitized its music manuscripts and made those images available on the internet for study.

Nevertheless, reconstructing it was a painstaking process, which took Dittamo about six months. Working from the digitized manuscript, Dittamo used image-altering software to sharpen resolution and alter tint and brightness.

“It’s not as high-tech as one might think,” he says. “But imagine, though, a few decades ago this capability wouldn’t be available to a random person.”

First, he had to figure out what was missing from the manuscript, as well as accounting for any errors by the scribe.

“You often have to infer what the original notes were based on context clues,” he says. “If you have a smear of darkened ink that’s about yea wide, you know it’s going to be one of maybe four notes, but which one? You have to use your judgement.”

Additionally, scribes wrote voice parts separately, without barlines.

“It’s just a continuous stream of music,” Dittamo says. “You have to get the voices to align, which is kind of like a musical jigsaw puzzle.”

Once he’d figure out the notes and put them in modern notation, then he worked with the text.

“In this era, they wrote the whole word underneath the music where it starts. The singer was expected to have acquired in their training a sense of taste as to how one should apply the syllables,” he explains.

Similarly, scores did not include sharps or flats, dynamics, articulations or tempo marks.

“It was expected that any salient nuance they would do themselves,” he says.

Of course, it helped that the composer was in the singers’ box with the chorus.

The Kansas City Chorale previews its upcoming performance of Bartolomé de Escobedo’s “Missa Ad te levavi”:

The Kansas City Chorale performs the result on May 5 and 7, as part of a program inspired by the travels of 13th century merchant Marco Polo, and brings together musical traditions from China, the Middle East, India and Mongolia.

Charles Bruffy, the Chorale’s artistic director, feels like an archeologist.

“We get to share a piece of human history,” says Bruffy, “connecting the sounds of the Sistine Chapel from half-a-millennium ago with the modern age.”

The Kansas City Chorale presents "Hidden Treasures: The Travels of Marco Polo," 2 p.m., Sunday, May 5 at Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, 11th and Broadway, Kansas City, Missouri 64105; 7:30 p.m. Tuesday, May 7 at Our Lady of Sorrows, 2552 Gillham Road, Kansas City, Missouri 64108.

KCUR contributor Libby Hanssen writes the culture blog Proust Eats A Sandwich. Follow her on Twitter, @libbyhanssen.