Randy Brown was barely talking yet when his father shipped out for Vietnam. To close the distance over the course of that deployment, Brown's parents made recordings for each other.

"The first time that he heard my tiny, little voice was probably on one of those little three-inch audio reels," says Brown, who is now retired from the Iowa Army National Guard.

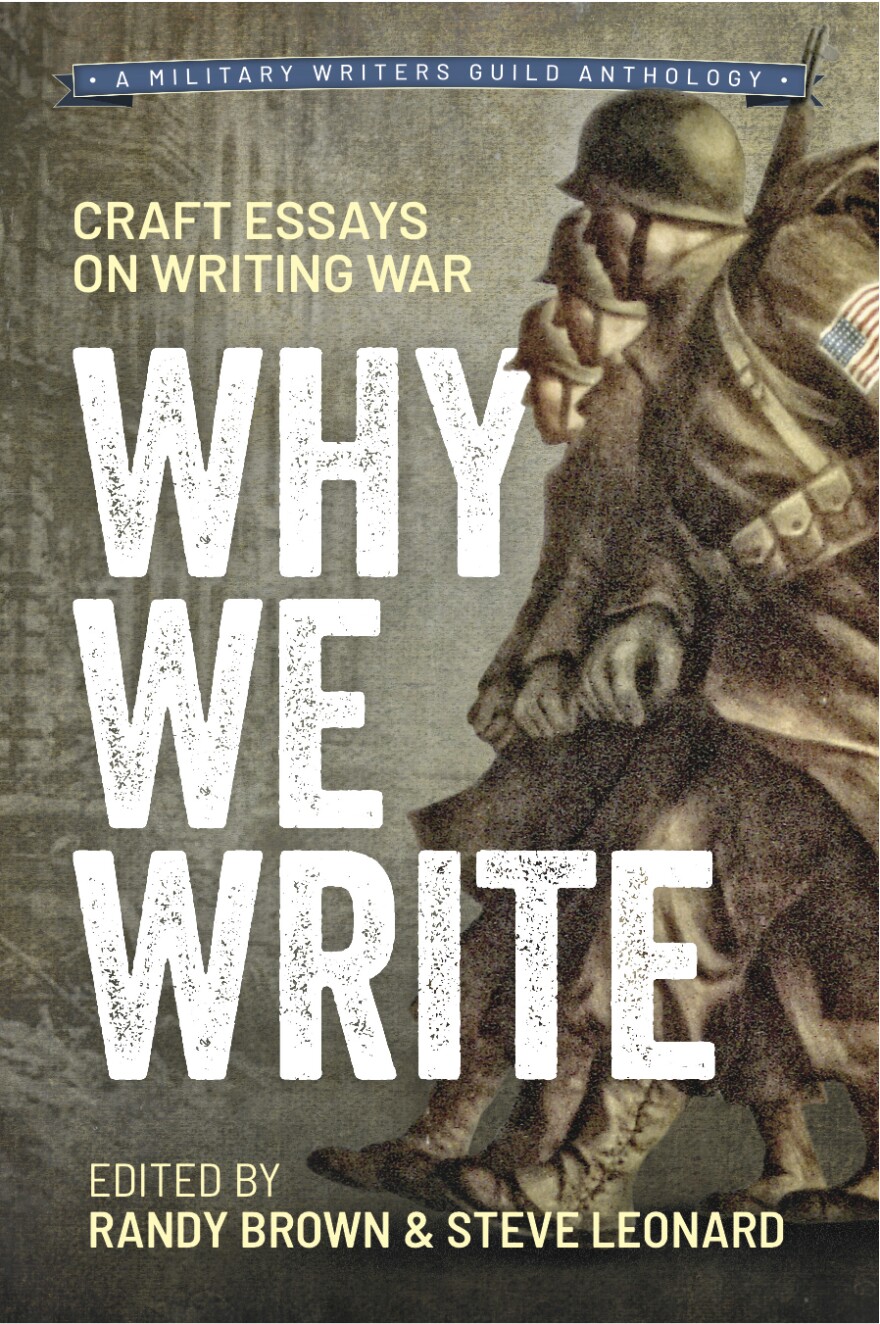

This is part of the genesis story of why Brown writes. He and Steve Leonard, who directs a program in organizational leadership at the University of Kansas and served in the Army for 28 years, have edited a collection of essays with similar explanations and explorations. It's called "Why We Write."

Sixty-one writers, military and nonmilitary, contributed written work.

Leonard says he hopes the book will inspire others, military and non-military, to tell their stories. He cites a teacher who once encouraged him.

"He believed if you don’t tell your stories, no one else will, and you’ll lose your opportunity to leave a legacy behind," Leonard says.

Part of Brown's legacy, it turns out, is recording experiences when a father's deployed. Ten years ago, Brown left his own young family for Afghanistan. Like his father, he found a way to keep his family close. Instead of making tape recordings, he started a blog called Red Bull Rising.

The response was not what he'd expected.

Other military families, whose servicemembers were not writers — maybe not good communicators at all — contacted him to say he was providing missing pieces of information. Thanks to his blog, strangers could better understand what their soldiers, sailors, airmen and marines were experiencing.

"The real reason that we're writing is to create opportunities for conversation and empathy and understanding and to have that present in the pages of this book," says Brown, a freelance writer and editor who lives near Des Moines.

The writers included in the anthology cite these same reasons for why they write. They also say they do it to grapple with circumstances and decisions they'd never imagined encountering.

In his essay, Phil Klay, whose "Redeployment" won the 2014 National Book Award for fiction, says he wrote "about the moral decisions soldiers face, decisions happening at a much lower level than the broad political debates most people think of — should we have gone in, did the Surge really work, what is victory supposed to look like in such a murky war — but decisions nonetheless of huge moral consequence."

Former civilian Army advisor Marcia Byrom Hartwell had another take. She explored bridging the civil-military divide through writing.

During her time embedded in Iraq, she came to know the military as a complex and diverse organization. Other Americans didn’t see it her way, and Hartwell was unprepared for the apathy she returned to.

"Americans look the other way as we engage in endless wars," she observed, so those who are apathetic need someone to explain "why our lessons-learned are relevant to our current political and military decision-making process. Our fellow citizens must be made to pay attention to the consequences of actions being taken in their name."

Brown says the anthology can serve as an important conduit between cultures or generations.

"Seeing those bridges of commonality is yet another example of why I think military writing or writing about war is so important anyway," Brown says.

Leonard says that this book is the first in what they hope will be several by the Military Writers Guild, to which he and Brown belong.

He emphasizes that this book, and certainly those in the future, are for anyone who has a story to tell. As far as he’s concerned, that's everyone.

Follow KCUR contributor Anne Kniggendorf on Twitter, @AnneKniggendorf.