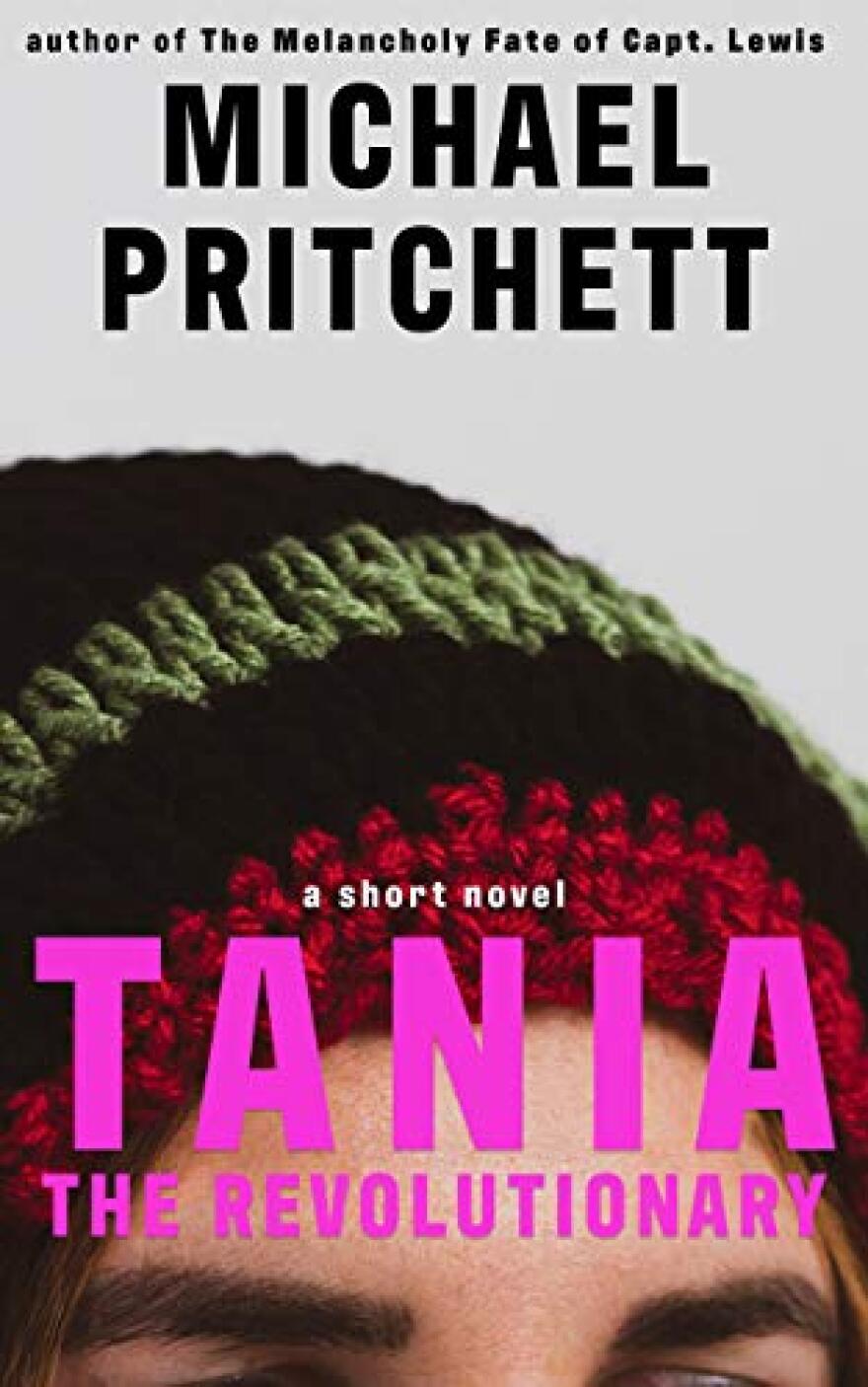

Michael Pritchett’s new work of fiction packs a lot into a small space. "Tania the Revolutionary," the University of Missouri-Kansas City professor’s third book, is named for what Patty Hearst called herself while held captive by the Symbionese Liberation Army in the early 1970s.

He sees that time-period as rife with what he thinks of as culturally-induced hysteria — pretty similar to the current climate.

“Hysteria is something that I have been sort of studying throughout my writing career, and it’s something that I’m always writing about in one way or another,” Pritchett says.

And that thinking led to this novella, about a young woman who’s fallen prey to a character looking to organize around and spread the feeling of hysteria. Pritchett says the idea for the story had been percolating since his own adolescence, when he followed the news about Hearst’s abduction and the Manson Family murders.

“I got interested in the idea of somebody who has been through an experience that is similar to Patty’s, and I think this happens to a lot of people,” Pritchett says. “They lose control of their lives through meeting some charismatic, controlling personality who kind of takes them over.”

He says the feeling is sometimes called an anxiety disorder, but that more than being about an individual’s personal psychology, the disorder is culturally induced.

“I think that it’s playing out very profoundly in both the COVID crisis and in what we’re seeing with the Black Lives Matter movement,” he says.

As Manson and the leader of the Symbionese Liberation Army found, wanting to spread the feeling is a good way of recruiting people, “and it also gets a lot of actions accomplished that wouldn’t otherwise be accomplished if you were trying to recruit people who were calm and relaxed and in a fairly passive state of mind,” he says.

However, hysteria does tend to cause actions that people on the outside of the feeling can view as excessive, like violence or destruction of property.

And that, Pritchett says, might make "the people involved in taking those actions look like they’re being irrational or being crazy, and I think in fact people aren’t being irrational or crazy, they’re being pushed by their culture to feel this hysterical feeling and to act on that hysterical feeling."

"Tania the Revolutionary" focuses on the aftermath of this kind of experience, telling the story of a Midwestern girl named Judy, who's escaped a cult and reunites with her mother.

Like Pritchett when he was young, Judy and her mother hang on every radio broadcast concerning Hearst or Manson. The stories frame Judy’s own healing from having been held, if not captive, at least in thrall to a charismatic male leader. And more than that, her eyes open to a larger societal issue.

“I think what she starts to think about the Patty Hearst story and the Charles Manson story in combination, is that we are very frightened of the sexual power and the sexual energy that is locked up inside the basic young woman,” Pritchett says.

As Judy compares those experiences to her own, it becomes plain that everyone around her, not just her abductor, but the church, law enforcement, men in general, and even women to an extent, are all frightened by the sexuality of young women and want to control it.

Though the story of Judy’s ordeal is never fully revealed, the reader gets glimpses of what she endured. Even the book's title is a hint. Like Manson and Hearst’s captor, Judy’s “guy,” as he's called, used a variety of nicknames to gain control over Judy.

“I think what it does is it starts to destabilize your identity and force you to give up everything that that identity—whatever that name embodies for you—to give that up and try to experience life without that kind of protective label that our names gives us,” Pritchett says.

Name-calling isn’t confined to the victims. The counterculture of the 1970s seized on the term “pig” to describe anyone who was not “enlightened,” Pritchett explains.

“That word got aimed at members of the military, members of the police, members of the government, members of the FBI, you know, pretty much all of the authority figures got labeled in various ways,” Pritchett says.

He’s not surprised to see a resurgence of the term now in light of the societal upheaval surrounding police brutality and the Black Lives Matter movement.

Pritchett says, “It still has power to refer to somebody who is not enlightened, and it makes the person who is being called a pig— it sort of brings them up short and causes them to ask themselves: Is there something disgusting or awful about my behavior that I need to look at, and I need to change?”