For more stories like this one, subscribe to Real Humans on Apple Podcasts or Spotify.

A year into the pandemic, there are two kinds of social distancers in Kansas City, and these two kinds of distancers harbor two very different post-pandemic fantasies.

Some of us live in close quarters with other people of varying ages and we may not always admit it, but despite our gratitude for companionship, we have spent much of the last year fantasizing about alone time. A single solitary experience — nothing more, nothing less.

In my version of this fantasy, I'm sitting alone on a restaurant patio. I'm eating breakfast and drinking fresh squeezed orange juice and wearing sunglasses (I don't own sunglasses). There's a perfect gentle breeze and all is quiet. I have other, more sociable fantasies that include the people I desperately miss, but those fantasies come to me when I'm thinking. This one's visceral. It comes to me when I'm struggling.

On the other end of the spectrum are the many people who have weathered the pandemic thus far on their own. For people in this category, alone time is pretty much the only time there is. This group fantasizes not only about parties and restaurants, but perhaps more poignantly, hugging.

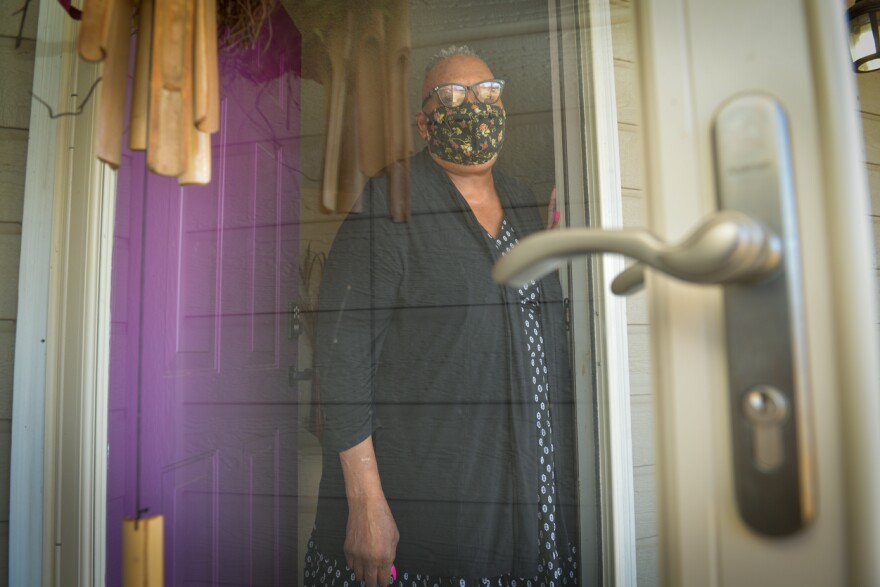

Wilma Gibson is the latter. It's been a year since she last hugged another person.

Gibson, in her late sixties, calls herself a homebody. But she works at her church, handling the organization's finances. That first Sunday of the pandemic, right before everything went on coronavirus lockdown, Gibson sent the minister a text asking him to discourage the customary exchange of hugs among parishioners. She didn't want to have to swat people away, but she says she would have.

"I'm not moving," she remembers telling him. "And I don't want anyone coming to me."

Two days later, lockdown began in earnest. Gibson remembers that she and her adult daughter each went out for one last grocery haul, and that Tuesday night, when they both got home to their separate houses, Gibson thought to herself: "We're in here."

Natasha Ria El-Scari, Gibson's daughter, just turned 45 this week. She's a poet, a social butterfly, and a mother of college-age kids. She also runs an art gallery. And El-Scari, like her mom, is single. Gibson is quick to point out that of the two of them, going a year without hugging and socializing has been harder on her daughter.

"I'm a homebody, so it doesn't bother me to stay home, but she has to go, she has to get out," Gibson says. "Natasha was staying away to protect me."

The discipline of it was never a question for El Scari. Her mom has sarcoidosis, a condition that affects her lungs, meaning as far as her daughter is concerned, "COVID would be a death sentence."

But it's been hard.

Early on, when very little was known about virus transmission, El-Scari and Gibson didn't see each other at all. Eventually, realizing that neither of them had gone anywhere, they started meeting for what they call "driveway visits" on Sundays: Gibson in her garage, El-Scari on the driveway.

At first, even that was kind of new and scary. In a recent Zoom call, they joked about their tentative early visits, remembering the days of neighborhood walks with about twenty feet of distance between them.

El-Scari laughs, adding, "I was that serious about protecting you. I was like, 'no games.'"

Since then, El-Scari has rearranged her furniture at home specifically so her mom can come over. Gibson has her own loveseat all the way across the room from the couch.

"We see each other often," Gibson says. "But we don't touch. Oftentimes we'll start to go toward each other and go, 'Oops. No, we can't do that.'"

This might sound like a small thing, but it's not. Human beings are wired for touch, particularly when we're stressed. Touch is a source of comfort that can help soothe us and moderate our emotions. Evolutionary biologist Robin Dunbar told The Guardian last month that the norm for our species is for any given human to have about five friends or family members with whom they routinely exchange touch.

"We touch each other more than we realize," he explained. "These intense coalitions act as a buffer; they keep the world off your back."

For people whose coalitions don't live in their households, the touch that typically comes with those relationships — whether we notice it or not — is gone. And with that comes a physical isolation more profound than the human nervous system was built to handle.

Gibson notices the absence of hugs most around hellos and goodbyes, but the desire to make contact was most painful at exactly the time it would have been the most dangerous: when her daughter had COVID.

Despite taking serious precautionary measures, El-Scari got sick in early November, and stayed sick for most of the month.

At points, it was scary. For a while, she was sleeping 22 hours a day. A friend who'd already had COVID came over in double masks to line up water bottles and pre-portioned food, then quickly leave.

"When I had a really horrible episode, my temperature went from 99 to 104, 105 in a moment," El-Scari recalls. "And I called my mom. I said, 'Something is happening.'"

Gibson walked her daughter through that episode, telling her to keep breathing, keep breathing. But what she wanted to do, hearing her daughter in distress, was physically take care of her.

"It was very hard because I did want to be there and care for her and change her bed and make her food. I mean, to take food to her and put it on the porch and run back to the car and to see her come to the door, that just tore me up," Gibson says. "Because I couldn't touch her. So I called her a lot and I probably woke her up a lot because I wanted to make sure she was awake. You know, that she was going to wake up. Cause it was bad."

It's been months since then, and El-Scari has a newly updated policy on hugging; she now hugs select friends who, like her, have already had COVID. For better or worse, she says, that's true for many of her friends. There's always a conversation about it beforehand. Spontaneous hugging is still out. And for El-Scari, social situations are still awkward, even in a mask, maintaining distance.

She tried going out recently, and it was stressful.

The people who'd been in touch and knew how seriously she was taking the pandemic kept their distance. "Like they just came six feet and then it's, 'Hey, miss you.' And we did the kind of hug yourself," El-Scari recalls. But the people who hadn't gotten the memo sometimes reverted, uncomfortably, to old habits.

"They just grabbed me," El-Scari says.

I ask what it will take for this mother and daughter to finally trade hugs.

"I don't know," Gibson says, pausing to consider it. "We could probably do it now."

"Mommy, I want you to be vaccinated first," Natasha interjects.

At 67, with a pulmonary condition, Gibson was still unable to secure an appointment when we spoke earlier this week, because appointment times in her neighborhood have been in short supply. But I just got word that she's finally on the books.

So the wait is almost over, but not quite. Until mother and daughter both have immunity, the air hugs continue, and these two Kansas City women find ways to hold each other up, without holding anyone at all.