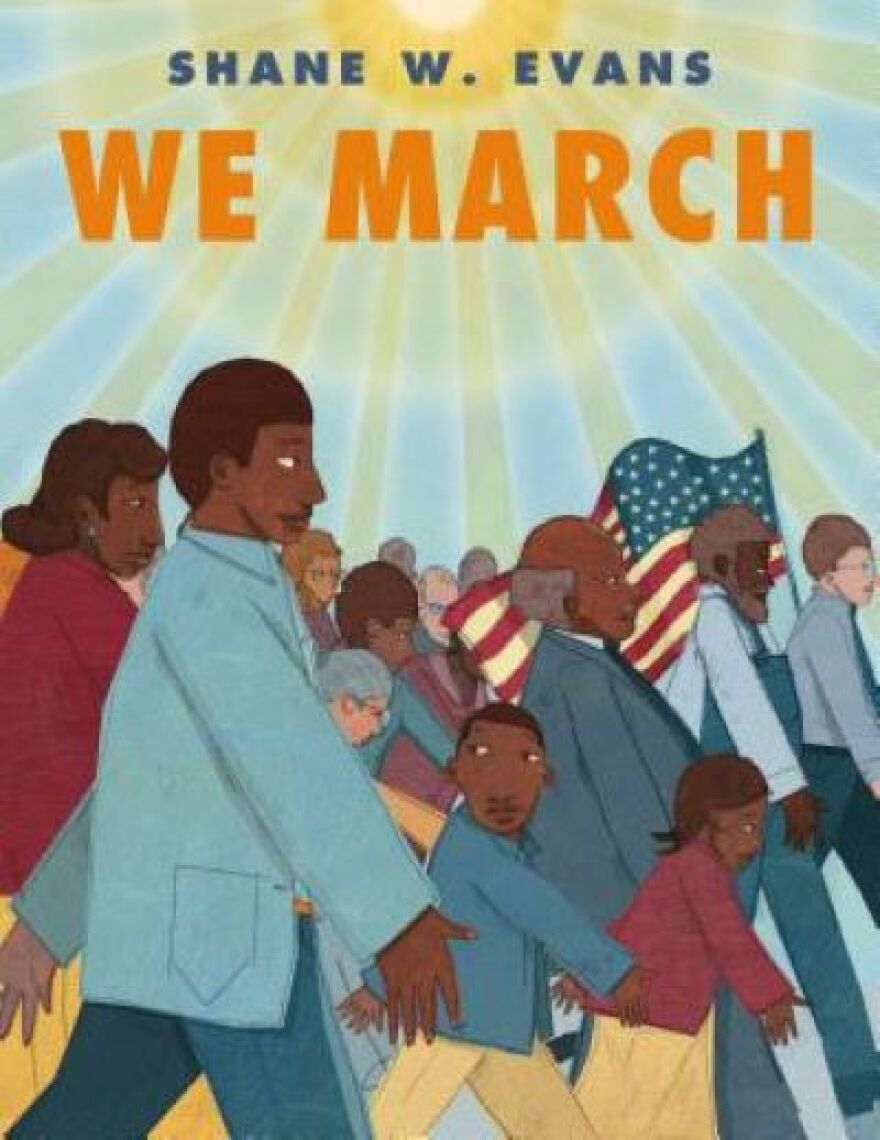

In March, Shane W. Evans discovered that one of the more than 30 children’s books he has illustrated had landed on the list of "Most Banned Picture Books Of The 2021-2022 School Year."

It wasn’t the first time.

Two of his other books — “Mixed Me,” which is one of five books he’s produced with best friend actor Taye Diggs, and “Hands Up” — have also been previously banned.

But the choice of "We March" was a real headscratcher for this Kansas City-based artist because it’s about a near-universally heralded historic event.

The sparsely worded picture book follows a Black family’s preparation and trip to the 1963 March on Washington, where Martin Luther King Jr. mesmerized more than 250,000 people with the “I Have A Dream” speech.

“We March” has been lauded as “highly recommended” for educators to use for children aged 5-9 by the educational site Teaching Books.

“We March” also is included in a Netflix Bookmarks Series project and it was on Kirkus Reviews’ Best Children’s Books of 2012.

The book is the sequel effort to Evans’ acclaimed book “Underground: Finding the Light to Freedom.” That children’s book is about the Underground Railroad that aided enslaved people, and won Evans the Coretta Scott King Award for illustration.

In both Texas and Pennsylvania, where it was initially noted as banned, “We Marched” ultimately passed scrutiny and remained available to students.

‘Another perspective’

Evans’ reaction to news of this latest ban was to see it as an opening “of a door for more sharing and giving.”

He began a crowdsourced campaign to put more copies of “We March” into the hands of more librarians, teachers and children.

Evans plans on delivering at least 101 copies of the books. More than $2,000 was raised in the first few weeks.

After all, the idea of being rejected, or critiqued is part of the process for any artist, Evans explained.

“Utilizing one person’s opinion or banned list or criticism should simply be a moment to be able to discourse, share another perspective,” he said.

On Monday, Evans read the book as part of a weekly gathering put on in the San Francisco Bay area by Bobby McFerrin.

McFerrin first became popular back in the late 1980s with his song, “Don’t Worry, Be Happy.” And Evans had previously appeared at the artists’ weekly CircleSongs events in Berkeley, California.

In writing “We March,” Evans purposefully chose a cadence and rhythm for the relatively simple wording accompanying the illustrations that fill the pages.

“The sun rises.”

“And we prepare.”

“To march.”

“We pray for strength.”

News of it landing on the banned list touched on some of his original intentions for the work.

“The focus for the rhythm of ‘We March’ is about harmonizing, no matter the dissidence and discord that some groups are having with these projects,” he said.

Careful consideration

Dialogue about why bans are happening, the feared impacts and rationales for those who initiate them was part of “Canceled, Censored, Banned,” a recent program jointly presented by American Public Square at Jewell, Kansas City PBS and the National WWI Museum and Memorial.

The panelists were Missouri Secretary of State Jay Ashcroft, ACLU Kansas Executive Director Micah Kubic, business owner and conservative political advisor Sally Bradshaw, and author and journalist Michael Ryan.

Last fall, Ashcroft introduced a new rule requiring public libraries receiving state funds to publish policies allowing parents to designate materials their children can access.

Ashcroft and his goals in doing so were a large part of the conversation between the panelists.

A concern for a parent’s ability to oversee what their children have access to in classrooms is often cited as a reason for such efforts around books, in school districts locally and nationally.

But what one person labels a ban often isn’t seen as being all that restrictive to another.

Bradshaw and Kubic both pointed out that in doing so, too often, one parent winds up deciding what all children can read, not just their own child.

Kubic also noted that the works targeted are often titles by African Americans or those with themes about LGBTQ+ people.

Ashcroft pushed back at several points in the discussion.

“This rule doesn’t ban any books,” he said.

And all the panelists concurred that an emphasis on critical thinking and civil discourse was necessary for such conversations.

Impact of bans

PEN America didn’t notify Evans that his work had made the banned list, which was published in February.

PEN counted bans at schools and found 1,648 books had been banned last school year. Most, the group reported, were written for young adults or adults.

But they also created a list of banned picture books like the ones that Evans illustrates and authors, finding 317 such works.

One possible impact noted by Kansas City area leadership consultant Nicole Price is that banning books might affect the development of empathy and compassion in young children.

“Through fiction, we can experience the world as another gender, ethnicity, culture, sexuality, profession, or age, and even experience another time period,” Price said.

In addition, she added, “Recent brain research suggests that reading literary fiction helps people develop empathy and critical thinking.”

The two bans that affected, at least temporarily, “We March” also point to how different people see those actions.

“We March” was included in decisions at two school districts, one in Texas and another in Pennsylvania, according to PEN America.

District officials in the central Pennsylvania school district of Central York said that an existing diversity resource list was merely rescinded for a time. “We March” was on a long list of about 300 titles the district recommended for teachers to use during classroom instruction.

The list had been put together as teachers looked for ways to help students in the wake of the 2020 George Floyd death in Minneapolis. A police officer was later convicted of the murder and the case was part of the spark for the nationwide Black Lives Matter gatherings.

In Texas, a review of more than 400 titles began in 2022 after Gov. Greg Abbott asked schools to research whether pornography or sexual content was available in public schools.

More than 100 books at the North East Independent School District, in San Antonio, were either removed or “updated,” with newer editions or books that had a similar theme, according to news reports. A search on a website maintained by the school district shows that “We Marched” will continue to be available for students.

Media reports noted discussions about how the books were never taken from libraries, nor were they banned from use in after-school periods.

‘Let it be’

A close inspection of what happened or who was behind the ban hasn’t consumed Evans’ attention.

Evans is well known in Kansas City and considers it a home base, although he was raised on the East Coast and travels widely around the globe, producing and performing his art and music.

He was educated at Syracuse University and initially arrived in Kansas City through a job at Hallmark, where he worked for seven years and considers the company his “graduate school” because he was exposed to so many talented artists with international ties, a path he’s followed.

Evans’ commitment to travel and work abroad also began during that period of his career. Japan was first. Then Venezuela, followed by Burkina Faso in West Africa.

He’s produced five books in collaboration with Diggs, the actor and Broadway star.

The first was also on a banned list at one point. "Mixed Me" is about a young child growing to understand and love the uniqueness of his bi-racial heritage, with the guidance of his loving mixed-race parents.

Some have tried to explain society’s current rapt attention to books accessible to children as a period of changing perspectives, especially because so many of the titles involve people of color or the LGBTQ community.

The final page of “We March,” differs from the rest of the text. It’s an explanatory message by Evans that’s clearly for adults. It’s several paragraphs about the historic implications of organized marches, noting how they’ve been used to advance common goals, often against resistance.

“It takes people of all ages and cultural backgrounds to move a nation into a new era of freedom,” reads one passage. “In a sense, these marches pushed old ideas out of the way and moved new ideas forward.”

The crowdsourced campaign around “We March” will likely end as April concludes. The intention was always to have it last about a month.

Once the campaign is complete, Evans said, he “will let it be.”

This story was originally published on Flatland, a fellow member of the KC Media Collective.