Drag has been a form of entertainment in Kansas City for nearly 200 years, but it didn’t start out with the flamboyant performances drag queens are known for today.

Lawmakers attempting to regulate and ban the practice isn’t new either. States across the country, including Missouri, are experiencing a wave of legislation targeting drag performances, some of which would make it a misdemeanor for drag entertainers to perform in front of children.

“If people would study their history, they would realize that we had laws against this 150 years ago and they didn't really take, and they're not going to take again,” says Stuart Hinds, curator at the Gay and Lesbian Archives of Mid-America, which works to collect, preserve and share material that reflects the histories of the Kansas City region's LGBTQ+ communities.

“Drag isn't a threat to children,” Hinds says. “It's a form of theater, and it's theater history.”

Hinds says the earliest recorded “female impersonator” – as drag performers were known before the mid-1900s – in Kansas City was in 1876, and was part of a minstrel show, an American form of racist theater entertainment.

This first known appearance of drag in the city wasn’t about appreciation, Hinds says.

“Minstrel shows are really about power and reinforcing the boundaries of power — not only over people of color but also over women,” Hinds says. “Most of the characters in a minstrel show are exaggerations. The best way to exaggerate being a woman is to have a man pretend to be a woman.”

“It was just another form of wrapping that whole notion of control and power into the overall minstrel experience,” he says.

The art form quickly evolved from exaggeration to mimicry with the popularity of vaudeville, a type of variety entertainment that became popular in the late 1800s.

This is when drag artists began to incorporate singing into their performances.

“According to the purveyors of vaudeville, you could take your children to the show and not worry about the show's content,” Hinds says. “That's where the practice of female impersonation, of drag, as it becomes known later, assumes a veneer of respectability and is safe for the family.”

Multiple drag performers rose to national prominence and toured all over the country during this time. Julien Eltinge, Bert Savoy, and Karyl Norman were just a few of the famous artists who toured through Kansas City during the heyday of the Shubert and Orpheum theatres.

“Eltinge was internationally known. He was the RuPaul of his day,” Hinds says. “He was known for the quality of his clothing, his makeup, his ability to ‘pass’ (as a woman) — because that was the measure of a good impersonator.”

Savoy and his stage partner, Jay Brennan, would put on exaggerated comedy routines, laden with iconic catchphrases — a familiar routine for modern drag fans.

Looming over performers throughout that early era was an 1860 municipal ordinance that made cross-dressing illegal. In Kansas City, it was against the law to appear in public in clothes that were “inappropriate” for one’s sex.

“The ironic thing is that as (cross-dressers) were arrested and charged for violating that ordinance, the folks who were doing the same kind of behavior on the stage were celebrated and rewarded,” Hinds says. “We don't start seeing accounts of people being arrested until the very late 1870s and into the 1880s.”

Despite the ordinance, drag thrived in Kansas City, especially around Prohibition.

Prohibition, Pendergast and a safe haven for drag

From 1920 to 1933, drag enjoyed a period of relative comfort. Hinds says the illicitness of alcohol predisposed people to accept other restricted activities as well.

“Folks were still going out to clubs and consuming liquor, which was illegal,” Hinds says. “There was a mindset of, ‘It's OK to do other things that are a little more risque and perhaps illegal.’”

“There was a mentality of acceptance of things that were previously considered taboo — things like drag,” Hinds says.

During Prohibition, there were huge drag balls across the U.S. In Kansas City, drag performances spread throughout local nightclubs.

When the 21st Amendment repealed Prohibition in 1933, drag performances virtually disappeared in many places because of increased regulation and enforcement at entertainment venues that served alcohol.

But in post-Prohibition Kansas City, drag began to flourish. Thanks to Tom Pendergast's near-total political control of the city from the mid-1920s to the late ‘30s, venues operated the same way after Prohibition as during it: Liquor ran freely, and all forms of entertainment were encouraged.

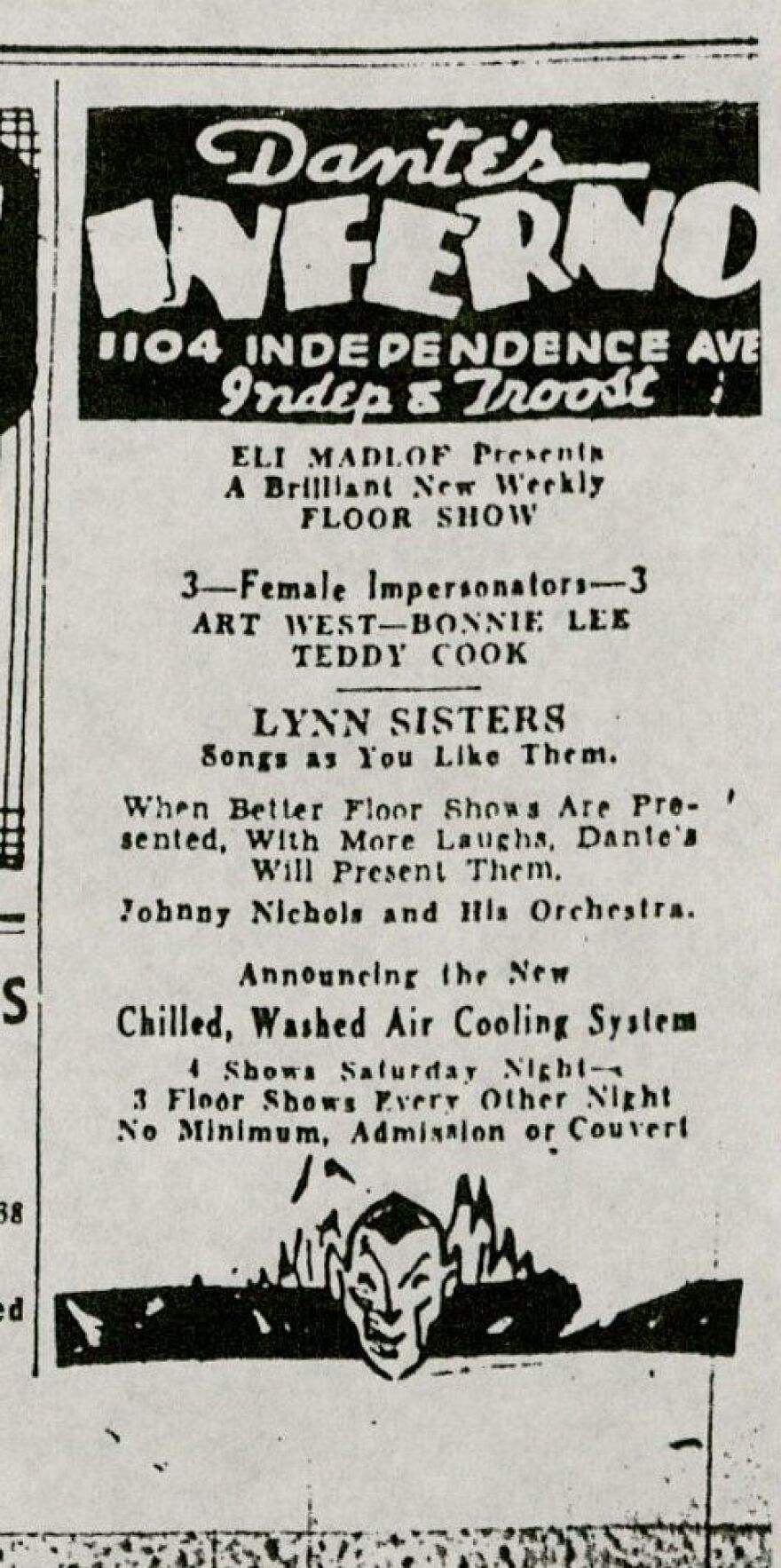

“Literally the day that Prohibition is repealed in the United States, a club opens at Independence Avenue and Troost, called Dante's Inferno,” Hinds says.

The club became the home of drag in Kansas City. And because drag was forced back underground after Prohibition, Dante’s Inferno and other venues in the city, including a few in the 18th and Vine district, were important stops for many nationally touring artists.

Kansas City continued to be an epicenter of drag until Pendergast’s reign ended in 1939, when he went to jail for tax evasion. Beginning around the time of World War II, there is not much evidence of drag in the city until the late 1950s.

An evolution into self-expression

In the late ‘50s, drag evolved again from mimicry to a form of liberation.

A bar off Troost Avenue called the Jewel Box Lounge began to host regular drag performances. It became so popular that the bar hosted multiple shows almost every night of the week to satisfy patrons.

“The Jewel Box becomes like Dante's 20 years before: the home of drag in Kansas City,” Hinds says.

“At first it tends to draw a pretty gay crowd — that's typically kind of what happens when you start to feature drag — and then it becomes more popular with straight folks,” he says. “Mom and Pop would drive in from Liberty or Raytown and go to dinner, and then go see a show of the ‘funny ladies’ at the Jewel Box and then go home.”

That era is the first time names of individual, local drag queens are preserved. Skip Arnold, G.G. Allen and Rae Bourbon were just a few of the well-known performers who propelled the Jewel Box to decades of success.

Edye Gregory and Rae Rondell, the first documented Black drag queens in Kansas City, also performed at the Jewel Box later in the club’s history. Gregory went on to win Miss Gay Illinois and was runner-up for Miss Gay Missouri.

“The Jewel Box was pretty white, to be frank,” Hinds says, “and it's not really until after Stonewall, into the ‘70s, that we start to see impersonators of color there.”

Other bars also began to feature drag performances, including the Redhead in Westport and the Colony Bar on Troost Avenue. No establishment hosted as many performances as the Jewel Box.

Kansas City had an active drag ball scene in the 1960s. The GLAMA collection currently has advertisements in the Kansas City Star for drag balls in 1965 and a printed invitation to one in 1968.

Kansas City was such a popular destination that anthropologist Esther Newton, who studied drag, used Kansas City as one of the case studies for her 1972 book “Mother Camp: Female Impersonators in America.”

It was one of the first scholarly looks into the world of drag queens, and Newton connected with Arnold for a look into the local scene.

In the 1970s, the Jewel Box’s success started to wane. Redlining, the Kansas City Race Riots of 1968 and individual business decisions spelled disaster for the club.

“They open up two clubs next door,” Hinds says. “One is a burlesque club and the other is a strip club — and when you put a strip club next to your drag bar, the strip club is drawing in a very different audience.”

“By the end of the decade, they're not doing as much business because Mom and Pop Raytown don't want to go to a nightclub that is just right next door to a strip club,” he says.

The Jewel Box eventually moved and lasted for about 10 more years, declining in popularity each year, Hinds says. After it closed, Rae Rondell went to work at Sarah Crankankle’s Cafe at 33rd Street and Gillham Road, a forerunner to Hamburger Mary’s that used drag queens as wait staff.

Bars continued to come and go for the next decade but drag remained prolific. And in the 1980s, the pageantry and comedy of drag were used to garner help during the AIDS epidemic.

Pageantry and philanthropy

When the first cases of AIDS in Kansas City were reported in 1982, the LGBTQ+ community turned to drag queens for help. They responded immediately, hosting benefits to raise money for the four local organizations providing help.

A drag troupe called The Kansas City Trollops formed in 1986 to perform comedy.

“They were just there to raise money, and what they ended up doing was raising spirits as well because it was a particularly dark time,” Hinds says.

Bars like the Cabaret became mainstays for local drag, and performers like Melinda Ryder and The Flo Show rose to prominence. With a comedic routine that featured exaggerated makeup and jokes, Flo was a captivating performer.

“The pageantry is really just expanding … it's just becoming this huge deal,” Hinds says. “There's a lot of that going on in clubs, but the need for fundraising around AIDS doesn't go away.”

In the mid-1990s, The Flo Show began giving all proceeds from a weekly show at the Cabaret to the American Foundation for AIDS Research. The show raised around $500,000 over the course of a decade.

“(She had) a working-class kind of maternal character: sassy and irreverent,” Hinds says. “Her shows were insanely popular. People are still very, very passionate about them today.”

Around the same time, a group called Late Night Theatre began performing routines of cultural milestones like “The Stepford Wives” or Alfred Hitchcock’s “The Birds” in drag.

Both Flo and Late Night Theatre still perform.

Since Kansas City was established, drag in various forms has entertained and provided an outlet for self-expression.

Hinds says he doesn’t understand the current backlash against it, but he does see similarities between the way drag is treated now and how it was dealt with more than 160 years ago.

“There's this outrage, and arrests again of people on the street in the real world,” he says. “And that's kind of what we're seeing again now: If it's in the real world and my kids can get to it, it's really not OK. But we'll let it be OK on the stage where kids can't get to it.”