Willa’s Books and Vinyl is technically closed to the public.

But, on a hot Tuesday afternoon in July, the doors to the storefront along Troost Avenue and 56th Street keep swinging open.

Owner Willa Robinson stays busy inside, preparing to move her vast collection out of the store. In the main room, books by Black authors remain on the shelves. But there are signs of Robinson’s upcoming departure: boxes of books and vinyl are scattered around the store.

“I got so much stuff I got to pull out of here,” Robinson says.

Frequent patrons of the store come inside to chat with “Miss Willa,” as she’s affectionately called, and browse the selection of music and literature. Some are surprised to hear she’s retiring and closing the store.

“I’m not selling anymore,” Robinson tells one customer looking for gospel records.

“That’s messed up,” he says in disappointment.

But Robinson, who has run the longest-standing Black-owned bookstore in Missouri, still wants to help.

“If you wait around,” she tells the man, “I might be able to help you.”

Collecting and selling Black books and records has been at the center of Robinson’s life for decades. At 84 years old, she’s entering a new phase in her life — as is her beloved bookstore. Last weekend, friends and supporters of the store celebrated Robinson and bade goodbye to Willa’s Books and Vinyl with the help of The Kansas City Defender, the Black-owned media outlet that will take over the space at 5547 Troost Avenue.

Robinson said she did not expect the outpouring of support at her retirement party.

“I was surprised, really, that they cared that much about the books,” she said. “This was just a wonderful ending of it.”

"Like you’re walking into someone’s home"

The Defender, which has been covering the store’s rent since 2024, plans to turn it into a public archive and a community space. People will still be able to visit and browse some pieces in Robinson’s immense collection, but the books and magazines won’t be for sale.

Nina Kerrs with The Defender said the team acted quickly when they first heard of Robinson’s plans to retire. They learned how to preserve and archive the thousands of books, magazines, CDs and vinyl records Robinson has collected over the years.

“This being the longest-standing Black bookstore in Missouri, it is very scary and critical for that to just be wiped out of our community, especially with the loss of Black history in the education system,” Kerrs said.

Kerrs remembers the first time she walked into Willa’s Books and Vinyl in 2023. Music played from the turntable, and there were books everywhere. Kerrs stayed and talked with Robinson for hours that day.

She said Willa’s Books and Vinyl feels “like you're walking into someone's home.”

“That was my first feeling, is safety,” Kerrs said. “Being in the Black community, having somewhere that you feel safe to be yourself truly is very rare.”

The Defender’s team especially wanted to learn how to preserve Robinson’s archive, which includes books dating back to the 1800s.

“She has some of the first books, written by Black people, recorded,” Kerrs said. “It is really, really beautiful. Even books that, when she's shown them to me, they're almost crumbling in our hands.”

"I wanted children to know their history"

Robinson began collecting books in the late 1970s. At the time, she was interested in books about the Holy Spirit, she says.

“So when I went down to Salvation Army, they would always have books on the Holy Spirit, and they would have books on Black people,” Robinson said. “I wanted to collect books by Black authors. That was my whole thing.”

Robinson’s avid search for books by Black writers took her to thrift stores, estate sales and places outside Kansas City.

“I am a hunter,” she said. “I would be there early as I possibly could, and I would be there until it was time to go.”

She wanted old books that they “didn’t sell in Barnes and Noble.”

Growing up, Robinson said she doesn’t really remember reading books written by Black authors.

“We very seldom saw Black children in books,” she said. “So it was important to me to put books in my store where they could see their faces in a book.”

Robinson began selling books while working for the U.S. Postal Service, out of an empty room inside the Richard Bolling Federal Building in downtown Kansas City. She had to stop after the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995 led to tighter restrictions in federal buildings. Robinson took her growing book collection to 18th and Vine, where she’d set up a stand during events like the Jazz Festival or Juneteenth.

She opened her first store, Willa’s Books, in 2007, on Troost Avenue. In 2015, she moved to an office building on East 63rd Street, joining more than a hundred other Black-owned businesses. Those tenants, including Robinson, were forced out in 2021 when a developer purchased the building to demolish it and turn it into apartments.

Robinson reopened Willa’s Books and Vinyl at its current location in 2021. By her estimate, she’s collected around 15,000 pieces of art over the years — all by Black people. Some of her rarest finds are kept behind a glass case by the register, including a first edition book by Frederick Douglass from 1864.

“That's one of the reasons that this bookstore is here, is because I wanted children to know their history,” Robinson said.

"They can sell it for less"

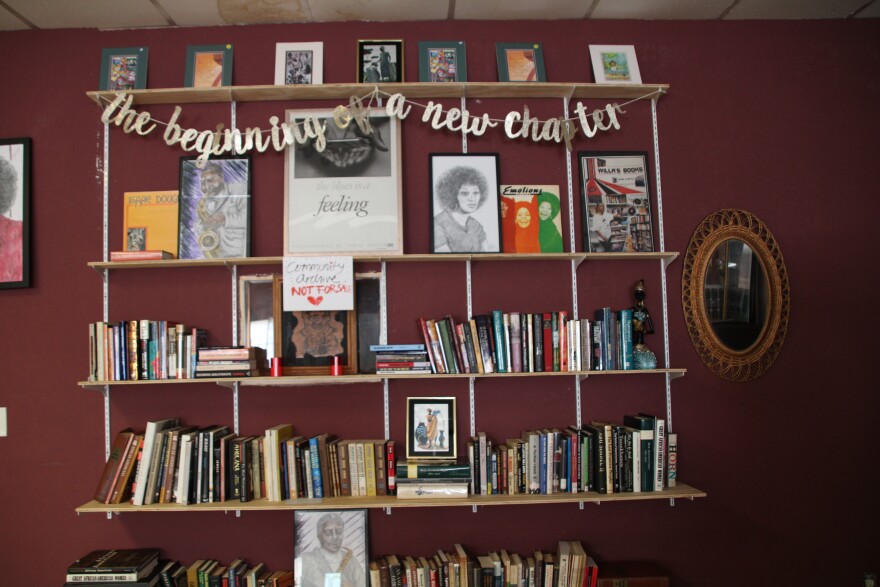

Parts of Willa’s Books and Vinyl are already showing hints of transformation. In the second room, a shelf is lined with books by Black writers, including novels and works of nonfiction covering abolition and Black history.

A banner that reads, “the beginning of a new chapter” hangs along the top shelf. Stacked nearby are copies of Ebony magazine stretching back decades.

“She's kept them alive for so long, which is so beautiful,” Kerrs said. “We can honor her legacy by preserving them as best as we can, to have it for future generations of Black people.”

Though she’s loved the recent outpouring of support, Robinson knows how difficult it’s been to stay afloat as a bookseller.

“There are books in this place that you cannot find on Amazon, you cannot find it in Barnes and Noble,” Robinson said. “But the thing that has gotten us, that messed us up: they can get it to you fast. They can sell it to you cheaper.”

Lauren Winston with The Defender said she wants the new space to carry on the traditions Robinson established in her store, and remain a space where Black kids and teens can feel safe and explore their curiosity through physical media.

“Especially in a time where higher education is going to become less accessible for disinvested communities, we just want to make sure that there is a space where we, the community, can also encourage education our way,” she said. “And tell our stories in the way that we want to see them.”

On that same Tuesday afternoon, as Robinson continued packing up the store, a family with two children wandered inside to look for books — just as Robinson had always intended.

Robinson invited them to take a picture with her holding a copy of a Congressional resolution honoring her contributions to Kansas City and her store as a “beacon of knowledge, dignity and Black heritage in Kansas City.”