High-speed car chases are familiar scenes in movies and on TV — cop cars flying down the streets and highways with their sirens blaring, trying to keep criminals from getting away. But what many don’t realize is that in real life police pursuits are dangerous, and often end in crashes or — in the worst cases — death.

In Kansas City, the risky business of police pursuits is even more complicated because of the state line. Most, if not all, police agencies have a policy that says what officers can and can’t do during a pursuit. In fact, in Missouri, they’re required by state law. They spell out things like how fast officers drive, when they call a supervisor and who they’re allowed to chase.

In Kansas City, two states, six counties, and dozens of municipalities all have their own pursuit policies. The multitudes of jurisdictions come together on a map like a crazy quilt.

"Ninety-Fifth and Mission is an example," explains Chief John Meier of Leawood, Kansas, "you've got Leawood, Prairie Village, and Overland Park all at one intersection. And so, you can be through Leawood, into Prairie Village, out of Prairie Village and in Overland Park within just a matter of blocks."

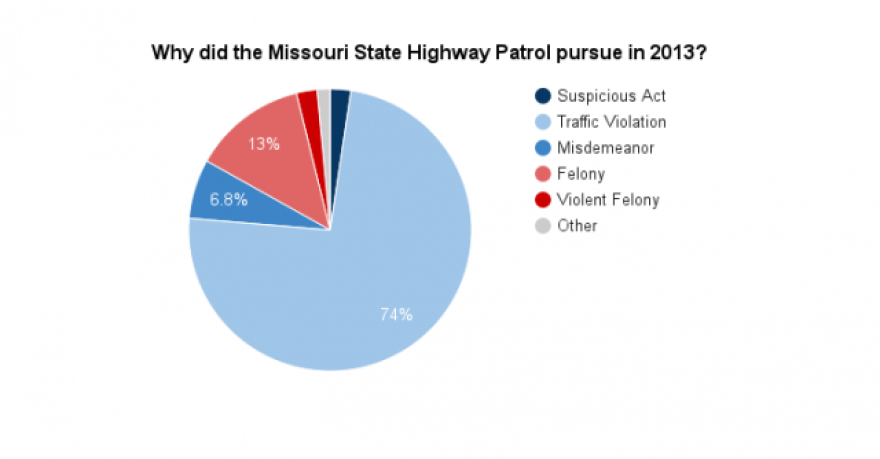

The policies vary greatly. Some allow you to chase for something minor like a traffic violation. Others only allow pursuits of violent felons. Chief Meier says police dispatchers have a particularly tough role to play in pursuits because they have to know where the pursuits are headed and then talk to those departments.

Greg Damron, the senior dispatcher in Leawood, says although pursuits aren’t any more stressful than other police situations, dispatchers have to be able to see the big picture.

"It's challenging, I mean you can sit here and document everything that's said on the radio, but if you're understanding where the pursuit is, where it's going, what agency it's going into and you're notifying those agencies, and you're getting all the other resources that you might need involved, at that point it can be challenging," he says.

Even if you live somewhere like Leawood that adheres to a pretty strict policy, you could still be at risk. Cross jurisdictional pursuits happen fairly often. And pursuits can be really dangerous.

"Normally, when a pursuit ends, if it doesn't end in a crash, it ends with someone bailing out and running on foot," says Meier.

In the last decade in Kansas City, there have been at least 706 pursuit crashes that have killed at least 23 people – many of them innocent bystanders. Hundreds more were injured, including 11 police officers. Some might question, are pursuits even worth it at all?

Aaron Ambrose, former Grain Valley, Missouri police chief and current insurance risk manager says most of the time, they aren’t. But there are exceptions.

"Now, if somebody's grabbed a little kid and they're holding them hostage — some kid has gone into the neighborhood and snatched them up and they're driving around, I say we follow them until the wheels fall off, you're never going to let that vehicle out of your sight regardless," he says.

“That's him probably about a month before he was killed at school. It was kind of a, I think one of the kids just caught him …” says Cheryl Cooper, whose 17-year-old son Chris was killed when a drunken driver being pursued by Independence police hit him on his bicycle in 2007.

She agrees that sometimes pursuits are necessary. But, she says she’d like to see stricter policies across the metro, policies that only allow pursuits for felonies.

"Someone who is putting the public in danger then yes, of course. But, over a stolen car or a busted tail light or an expired license plate ... it's not worth putting innocent people's lives in danger. Never is it worth that," Cooper says.

Cooper now works with pursuitSAFETY.org, a group that advocates for safer pursuit policies nationwide. Her house is filled with pictures of her son.

“The thing about pictures is I'll never get another one, I just have to you know put up as many as I can of him," she says.

Some people, like retired Raytown police chief Kris Turnbow, think a unified policy for all jurisdictions in the metro could ease the problem.

"I just think, that in this case a regional policy makes sense because some jurisdictions are so small and we pass through them so quickly that they can assist in a chase and understand what the parameters of that pursuit are," Turnbow says.

But some chiefs, like John Meier in Leawood, would rather be in total control of what happens in their jurisdiction.

"I am the one who is going to be held accountable for the officers of this police department. And, if I'm going to be held accountable for them, then I want to be the one who sets the parameters and determines what their actions are," he says.

Some people think the Mid-America Regional Council may have a role to play in standardizing policies. While the organization hasn’t looked at these conflicting policies in the past, executive director David Warm says it would be worth looking into in the future.

This investigative report by Mike McGraw and Bridgit Bowden was produced in collaboration with KCPT and KCUR. See also this story on why bystanders injured in Missouri police pursuits face uphill battles in court.